In his introduction to Heaven on Earth: Painting and the Life to Come, T. J. Clark makes it clear that the subtext of the book has to do with the efforts in the past and of today to impose a heaven on earth.

The key word there is “impose.” Often, this involves a religiously visioned paradise, such as promoted by the Spanish Inquisition or by some of today’s American fundamentalist figures. But it also includes or has included Marxism, National Socialism and the present-day arguments of the more extreme liberal U.S. politicians.

Very cut-and-dried stuff, these paradises, black and white. The nation will be better if everyone has a gun. The nation will be better if no one has a gun.

The core of Clark’s 2018 book, however, is his examination of four painters who portray the intersection of the everyday and the other-worldly, of the nitty-gritty and the spiritual, in a much more nuanced way.

Shrewd and subtle

In two of the paintings — Giotto’s Joachim’s Dream (1303-05) and Nicholas Poussin’s Sacrament of Marriage (1648) — this intersection takes place in a religious setting.

However, as Clark’s shrewd and subtle readings of the works show, these artists aren’t echoing the prose of catechisms but the poetry of vivid life. There is something mysterious going on in these paintings, spookily ambiguous, something that hints at much beyond the mundane what-you-see-is-what-you-get.

The heaven that Pieter Bruegel the Elder portrays in Land of Cockaigne (1567) is a comic one, a kind of Paul Bunyan or maybe Walt Disney paradise of food where houses are edible, fences are made of sausages and an egg runs around with a spoon in its open top for someone to grab and slurp the white and yoke down.

It’s certainly no direct challenge to religious orthodoxy, but there’s a gravity, physical and emotional, to its jokey-ness that signals something about dreams of a perfect world.

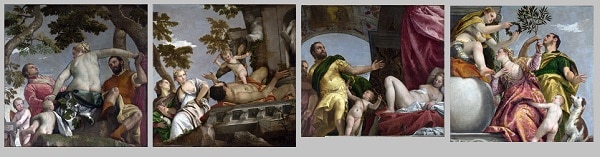

The four Allegories of Love paintings of Paolo Veronese — Infidelity, Scorn, Respect and Happy Union (all 1570-75) — may not seem at first to deal with heavenly things at all since their subject is sex and romance. Yet, the title Clark employs for his chapter on the works “Veronese’s Higher Beings” is a signal of how he views them.

It’s not that the people depicted in the paintings are Greek gods or goddesses or that they are part of some mythic story. They are very much the same as the viewer…but not exactly.

Clark calls them “higher beings” because of the way Veronese has painted these images — in a manner that requires the viewer to look up at them or seems to, even if the image is hung at eye level. Here is other-worldliness that isn’t about a paradise but is about some hyper-sense of the everyday work we inhabit.

“Intersection of earth and heaven”

In Joachim’s Dream, the husband of Anna is shown getting a message from an angel while sleeping. He’s out in the fields because, although wealthy and pious, he has been thrown out of the Temple by the high priest. Obviously, the thinking is, God does not consider him a good man since, for twenty years, he and Anna have been childless.

The angel’s message, delivered two days in a row, is that the couple will bear fruit in the form of a daughter. This child has been miraculously conceived by God — hers is an Immaculate Conception (later, the subject of a Roman Catholic feast day) — and will become, in a similar manner, the mother of Jesus, the Messiah.

Clark, who calls Giotto “the Shakespeare of painting,” has much to say about this painting and its meaning. Perhaps the most pertinent words are these:

The painted rectangle in Giotto is uniquely electric with its enclosing limits, filling every inch of the panel with the same decisiveness, and with every lesser internal element speaking its place in an order derived from the panel’s basic shape, because that shape, for the artist and his audience, was the limit of the world.

A picture was finite because it showed a necessary state — a specific intersection of earth and heaven — in the story of salvation.

“Outside the space of the visible”

A few pages later, Clark adds that the Dream suggests something even more:

What it depicts is an apparition; but it seems to want to show us that this appearing-in-the-world takes place in some strong sense outside the space of the visible.

After all, Joachim is asleep — in a dream world. The shepherds to the left can’t see what’s happening, even if they are able to see Joachim.

The message here seems to be that, in the life he is leading in the visual world, Joachim is also living in a place, at least in his dreams, which is other-worldly.

“Only More So”

The fairy tale of a land of unrestrained gluttony, Clark relates, had been around Europe for centuries before Bruegel painted Land of Cockaigne.

Most of the figures in the painting appear sated. Indeed, they are so glutted that they are lying full-length, even spread eagle, on the grass, even as various forms of food run around them and fall upon them.

Gravity and lassitude hold them down on the turf and, also, a peculiar weariness that seems to be, if not the opposite of happiness, a cousin of dissatisfaction.

Eternity here, writes Clark, “means nothing more than the mad wish for stasis — for final fulfillment and perfection — that is constantly present in workaday life, haunting it, taking advantage of it, making it bearable.” In fact, this glutton’s paradise doesn’t seem like much of a paradise at all.

Clark asserts that Bruegel is the opposite of a utopian, of someone with an agenda for creating a heaven on earth. But that doesn’t mean that, in his painting, “he reverses utopia’s terms, or is even straightforwardly a pessimist.” And he goes on:

It is typical of Bruegel that his vision of things transfigured, when at last he allows himself one, should not be The World Upside Down. The hereafter in Cockaigne is the world as it would be if it became more fully itself, with its basic structures unaltered and above all its physicality, its orientation, intact. The World The Same Way Up, Only More So.

Where she’s looking

For Clark, the meaning of Poussin’s painting Sacrament of Marriage hinges on the obscured figure on the left, half-hidden behind a temple pillar.

Despite the title, the scene is the betrothal of Mary to Joseph, a much older man than the rest of her suitors. The way Poussin has things arranged, Mary and the chief priest (a figure who looks in his beard and long hair like Michelangelo’s God the Father) are facing each other in a shaft of light with Joseph, shadowed, in between.

This makes sense inasmuch as Mary is already pregnant with Jesus by means of the Holy Spirit, the third person of the Trinity. (This was a second immaculate conception.)

The drapery and headdress of the figure on the left suggests that she is a woman, Clark writes, but he notes that they create an ambiguous enough image that the woman depicted might be looking out the window or opening to the left rather than at the betrothal.

“All that is mortal”

Clark sees this figure, despite its placement, as the key to the painting, at least in terms of how the visible world of the scene intersects with the other-worldly.

Poussin, Clark writes, decided

to mark a space apart from the sacred and have it be occupied, have its marginality be animate, embodied. The femme-colonne, dare I say it, is all that is mortal in opposition to the reach of the cross. She is profane, she is fleshly — all the more so for keeping flesh so completely under wraps.

The betrothal is still the center of the painting. Clark writes:

The sacred commands attention here; the center does hold…Nonetheless, it is entirely typical of Poussin that he should finally — in this last completed of his Sacraments — make such a space for the human apart from the drama of grace.

“Just out of reach”

Earlier in his book, Clark described Giotto as “the Shakespeare of painting.” And, now, in writing about Veronese and his four paintings, the Allegories of Love, he asserts that this 16th century artist

has a Shakespearean ability to use the sensuous and structural qualities of his medium — the exact disposition of light, space, color and shape within the picture rectangle — to make standard materials mutate.

In other words, to make the standard — the regular, the routine, the usual — something much different.

These four works by Veronese are standard paintings inasmuch as they are painted on a surface and meant to be seen. Because they are painted in a way that makes them appear to be seen from below, they are generally thought to have been done for a ceiling.

Clark, though, contends that the perspective isn’t as drastic as it would have been if Veronese had expected them to be that far over the viewer. Instead, Clark thinks they were probably done so that each could be set over a doorway.

The from-low-down perspective that Veronese has built into the paintings is odd, and so is the activity going on inside each of the four scenes. Because of the way the stories are told without clues about the location of things in relation to other things, it’s hard to know how close and far things are from the view, how people are oriented and how they are supported. There is, for the viewer, a “strangeness of space,” Clark notes.

For it matters profoundly, to repeat, that we are looking up into the worlds of Respect and Infidelity, and that this angle of vision tempers and complicates our whole response. The viewpoint….asks us to accept grandeur and precariousness simultaneously.

Not as an aspect of a world we can never hope to enter….but of one just out of reach. Familiar and tangible, but also superhuman. This is the pagan balance to be struck.

“Familiar, tangible and transfigured”

A few sentences later, Clark expands on this idea of “just out of reach.”

Always in the Allegories we are looking from low down, not into an utterly sublimated, superior space of the gods, but into a great construction: a clearing or a portico whose scale and logic are slightly (meaning decisively) beyond us.

Clark writes that to see these paintings, as we must, from below is to see their world “as if from the outside.” Not the outside of detachment nor of “awed inferiority.”

Perhaps we could just describe it as the outside of unfamiliarity….

We look up at the human comedy and are aware, above all, of its physical, spatial dimension. Standing and falling, balancing and unbalancing, the brick stump and the marble sphere. Familiar and tangible, to repeat, but also transfigured.

The people in these scenes aren’t gods. They’re humans who, because of the construction of the scenes, are higher than we are. They are, Clark writes, “higher beings, we recognize, but ‘higher’ here means the opposite of pitiless or invulnerable.”

Their strange space is like ours and isn’t. They are, in their way, above us, but we recognize ourselves in their awkwardness, uncertainty and shakiness.

Life Here and Not Here

These four artists, in the works Clark has examined, share a desire to examine the way humans experience otherworldliness in the visible, everyday world.

Each in his own way meditates on the junction of the nitty gritty and the spiritual. Or, maybe better put, on how humans think about and experience being in and out of their world simultaneously.

Except for this pondering of being in and out of the world at the same time, there is little commonality to these artists in these works.

There would be no way to build a program on their thoughts and insights. No way to develop a philosophy and a set of dogmas for making our world a heaven. These artists aren’t looking at the binary of earth and heaven.

Instead, they are looking at the shared space of the worldly and the otherworldly.

There is a messiness to their individual work and to the work of the four when studied together that would undercut any effort to create a new -ism for improving humanity.

Improving humanity isn’t what any of these artists is aiming for.

This is art that looks at human people as they are, recognizing that they are complex individuals and part of complex groups. They live in two places at once, the here-and-now physical and the whatever-you-want-to-call-it non-physical.

The title of Clark’s beautifully complicated study is Heaven on Earth: Painting and the Life to Come. In fact, though, he is writing about artists looking at what could be called Painting and the Life Here and Not Here.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.6.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.