Terry Pratchett — who died in 2015 at the age of 66 from Alzheimer’s — played for keeps.

His 41 Discworld fantasy novels are the height of playfulness. He plays with language, he plays with characters, he plays with descriptions, he plays with footnotes, and he plays with the reader. He’s the impish, slightly knowing guide, leading his readers on journeys into the heart of a strange, strange place — humanity.

Terry Pratchett was someone in love with humanity, recognizing the human tendency to heroism and compassion as well as greed and cruelty.

For all his goofiness and childishness on his Discworld pages, he’s never not serious.

Near the end of his 1996 novel Hogfather, Mr. Teatime — a very bad man, warped and bloodless (although he’s shed a great deal of other people’s blood) — pops up, stunned and speechless, in the midst of the wizards at the Unseen University.

In the interest of knowledge, a wizard hurries up to interview him about what happened, only to be pulled away by Archchancellor Mustrum Ridcully.

“I really should talk to him, sir. He’s had a near-death experience.”

“We all have. It’s called ‘living.’ Pour the lad a glass of spirits and put that damn pencil away.”

From the perspective of death

Some literary types have worked Death, as a character, into their fiction, such as Ingmar Bergman in his 1957 film The Seventh Seal and J.K. Rowling in her 2007 short story “The Tale of Three Brothers.”

None, however, embraced this idea with such vigor and gleefulness as Pratchett did, trotting out Death — a tall, almost humanlike skeleton in a long black robe with the traditional scythe — in all but one of his Discworld books.

You might call this a form of whistling past the graveyard, and maybe it was.

But I think that Pratchett understood what many humans try to ignore — that to really understand people, to understand those around you, to understand yourself, you need, at least some of the time, to look at life from the perspective of death.

But I think that Pratchett understood what many humans try to ignore — that to really understand people, to understand those around you, to understand yourself, you need, at least some of the time, to look at life from the perspective of death.

That’s not as morose as it may sound. After all, as Ridcully notes, being alive is a near-death experience. The moment I was born, I was dying. Pratchett, too. And you.

Death, the character, knows this. It’s what makes humans so fascinating for him.

“THEY HATE LIFE”

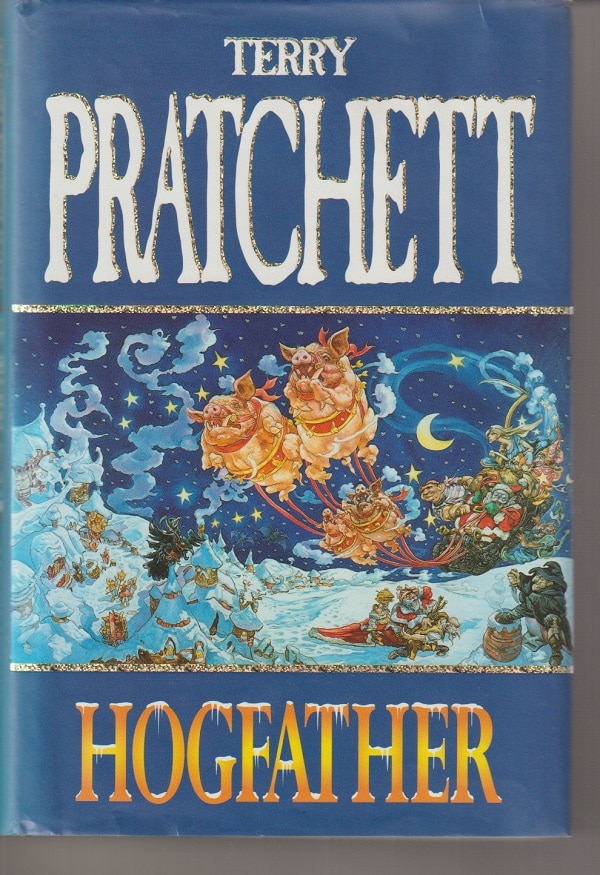

The plot of Hogfather has to do with an effort by The Auditors to kill or erase or disappear Hogfather, the Santa Claus of Discworld, on Hogswatch Eve when he’s supposed to deliver toys to the 20 million children of the Frisbee-shaped planet.

The idea is that, when Hogfather fails to deliver, the children will stop believing in him, and he will cease to exist. This is the first step toward undercutting human belief in other things, such as the Tooth Fairy and much more serious things.

These Auditors are vague gray shapes, ego-less, the perfect committee. Trying to explain them to Ridcully, Death, in his usual capitalized language, says:

“THEY RUN THE UNIVERSE. THEY SEE TO IT THAT GRAVITY WORKS AND THE ATOMS SPON, OR WHATEVER IT IS ATOMS DO. AND THEY HATE LIFE.”

“Why?”

“IT IS….IRREGULAR. IT WAS NEVER SUPPOSED TO HAPPEN. THEY LIKE STONES, MOVING IN CURVES. AND THEY HATE HUMANS MOST OF ALL. IN MANY WAYS, THEY LACK A SENSE OF HUMOR.”

But, Ridcully wants to know, why go after the Hogfather?

“IT IS THE THINGS YOU BELIEVE WHICH MAKE YOU HUMAN. GOOD THINGS AND BAD THINGS. IT’S ALL THE SAME.”

Little lies, big lies

Later, Death is talking with his granddaughter, Susan Sto Helit — she’s the daughter of his adopted daughter and his erstwhile apprentice, both of whom have, in the course of life’s twists and turns, died when their carriage plunged into a ravine — and she thinks he’s asserting that humans need fantasies to make life unbearable.

“REALLY? AS IF IT WAS SOME KIND OF PINK PILL? NO. HUMANS NEED FANTASY TO BE HUMAN. TO BE THE PLACE WHERE THE FALLING ANGEL MEETS THE RISING APE.”

He explains further that the Hogfather and the Tooth Fairy and other such seemingly playful ideas are actually important practice for humans.

“YOU HAVE TO START OUT LEARNING TO BELIEVE THE LITTLE LIES.”

“So we can believe the big ones?”

“YES. JUSTICE. MERCY. DUTY. THAT SORT OF THING.”

“They’re not the same at all.”

“YOU THINK SO? THEN TAKE THE UNIVERSE AND GRIND IT DOWN TO THE FINEST POWDER AND SIEVE IT THROUGH THE FINEST SIEVE AND THEN SHOW ME ONE ATOM OF JUSTICE, ONE MOLECULE OF MERCY.

“AND YET— AND YET YOU ACT AS IF THERE IS SOME IDEAL ORDER IN THE WORLD, AS IF THERE IS SOME….SOME RIGHTNESS IN THE UNIVERSE BY WHICH IT MAY BE JUDGED.”

“Yes, but people have got to believe that, or what’s the point—?”

“MY POINT EXACTLY.”

This is, says Death, “A VERY SPECIAL KIND OF STUPIDITY.”

Patrick T. Reardon

8.13.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.