The advertisement in the Vienna newspaper on February 2, 1771, was the sort of plea that has been repeated in one medium or another since earliest human times.

Three days before, “a Bolognese puppy, a white male all over and having blue eyes but with one lighter blue than the other and a small muzzle and a black nose, weighing seven pounds,” had gotten lost or wandered away. And its owner wanted to the world to know:

“Anyone finding or identifying it, should come to No. 222 Bognergasse up to the second floor, and is sure of gaining a good reward.”

This, reports historian Anton Tantner, was one of the first published uses of street numbers in the Habsburg capital of the Holy Roman Empire.

Indeed, in his tidy but wide-ranging House Numbers: Pictures of a Forgotten History, Tantner writes that, although the idea of giving homes and other buildings an individual number had a bumpy start, this system was in general use across Europe by 1750 or so.

Not everywhere, though.

In his 1932 book, The Radetzky March, German novelist Joseph Roth tells the story of Carl Joseph von Trotta, a cavalry lieutenant stationed in a town near the Russian border shortly before the start of the First World War. From the third floor window of his hotel, he looked down on the townscape:

“The streets had no names and the little houses no numbers, and anyone looking for a particular place had to follow whatever proximate directions he was offered. This fellow lives behind the church, that one opposite the town gaol, a third past the District Court. It was just like living in a village.”

A two-fer

Tanter’s book, published in 2015, is two-fer.

The first 64 pages feature his ambling, anecdotal-filled account of how and why house numbers came to be and how they have come to be used. It is likely that these are questions that hundreds of millions of the world’s people have never given a thought to. House numbers are simply something that, for such women and men, have always been there, so clearly useful as to be seemingly self-evident — like the wheel.

Of course, humans existed on the planet for some 200,000 years before the invention of the wheel, and even longer without house numbers.

The other part of House Numbers is a 119-page photo gallery of building numbers, such as this familiar one for Number 10 Downing Street, the official residence of the British Prime Minister and the headquarters of the United Kingdom government:

Or this odd fractional address for a bookstore in New York City’s Greenwich Village:

“Anyone not paying”

Not every place on the globe has house numbers. Tokyo, famously, does without them, as French essayist Roland Barthes describes in his 1970 book Empire of Signs.

Some 15 years ago, the German architect Michael Malwald was hired to introduce street names and house numbers to the Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa, home of more than three million people. Tantner quotes a newspaper story about the reasons behind the effort:

“The Ethiopian telephone service, the water and electricity systems too are awaiting the introduction of addresses. So that then they will be able to send out their bills.

“Until now people have been coming with their cash once a month to a collection point where they can pay their bills. Anyone not coming and paying has their water, telephone and power cut off.”

“Transparent”

That points out the double-headed nature of house numbers. Sure, they will save the Ethiopians the need to go each month to a collection point. But they also mean that those same people will be more easily found by bills demanding payment. At the start of House Numbers, Tantner writes:

The house number….wasn’t introduced so that people living and working in towns and villages could find their way around more easily. Nor was it intended to be particularly helpful to travelers.

Instead, it started life in that gray area between the military, the tax authorities and early modern policing.

In other words, building numbers may be useful in myriad ways, from me finding my friend’s home to Amazon dropping off a package at my neighbor’s business to you letting Uber know where to pick you up. But they were also an early version of privacy invasion, in this case, by the government:

A house number issued by the state…had the advantage of creating discrete, clearly distinguishable and fixed units. Once a sign was nailed on the wall of a house or painted on and left to dry, it was linked ineradicably as possible to the house. It enabled recruiting officers, tax collectors and court officials to know what was inside.

In effect, it made the walls transparent.

“Dividing line”

At times, this Big Brother-ism could be pernicious. As Tantner notes:

Everyone is equal before the law of the house numbers, it seems — or are they? Proof of the fact that a house number can also be used as a means of discrimination is provided by the way officials behaved under the Habsburg monarchy.

For Christians, a house address was given in Arabic numbers, such as No. 80. However, “Jewish houses,” i.e., those owned by Jews, “had to be numbered separately and in their case the number used were…Roman numerals,” such as No. XIV.

Here the sharp dividing line drawn between Jewish and Christian souls was further emphasized. The yellow patch that Jewish men and women had to wear on their clothing in Prague, which was only abolished in 1781, was thus affixed to their houses.”

“One officer was murdered”

Although Tantner makes no mention of any Jewish rebellion at this practice, there was strong and violent opposition to house numbers, for many reasons, at many places in Europe.

Even the nobles got involved.

Joseph II, the Holy Roman Emperor, thought he’d found a way to stop such contention in Hungary. The nobles shouldn’t complain if their castles are numbered, he argued, since the royal castle was as well.

It turned out differently, however: the ranks of nobles opening objected to the census and its commissioners. Some of the officials were beaten off from villages. One officer was murdered in the county of Veszprem, and another was sprayed with water and made to promise never to set foot in the district again.

“Systemless system”

For better or worse, house numbers weren’t going away, however. The system of numbering buildings became ubiquitous in much of Europe and the Americas, but that didn’t mean the systems from city to city were all that systematic, as Mark Twain found during a European tour.

“At first one thinks it was done by an idiot; but there is too much variety about it for that; an idiot could not think of so many different ways of making confusion and propagating blasphemy.

“The numbers run up one side of the street and down the other. That is endurable, but the rest isn’t. They often use one number for three or four houses — and sometime they put the number on only one of the houses and let you guess at the others.

“Sometimes they put a number on a house — 4, for instance — then put 4a, 4b, 4c, on the succeeding houses, and one becomes old and decrepit before he finally arrives at 5.

“A result of this systemless system is that when you are at No. 1 in a street you haven’t any idea how far it may be to No. 150; it may be only six or eight blocks, it may be a couple of miles.”

Even worse, he wrote, was that house numbers weren’t in sequence and didn’t flow in the same direction. The numbers might rise to, say, 50 but then jump to 140, and then to 139, and suddenly the numbers were going down now, instead of up.

Twain called it “a sort of insanity.”

More addresses

Complementing House Numbers, Tantner has a divertingly quirky website with a bunch of other photos of house numbers:

And here are several others from his book:

This two-ton sculpture marks the address of the Solow Building at 9 West 57th Street in New York City.

A stone number plaque with tumbling men, women and monkeys.

These numbers on a wall in Toulouse, France, show a change in the building number.

A playful way of numbering a building in Friesenheim, Germany.

A sculptural way of proving this house address in Paris.

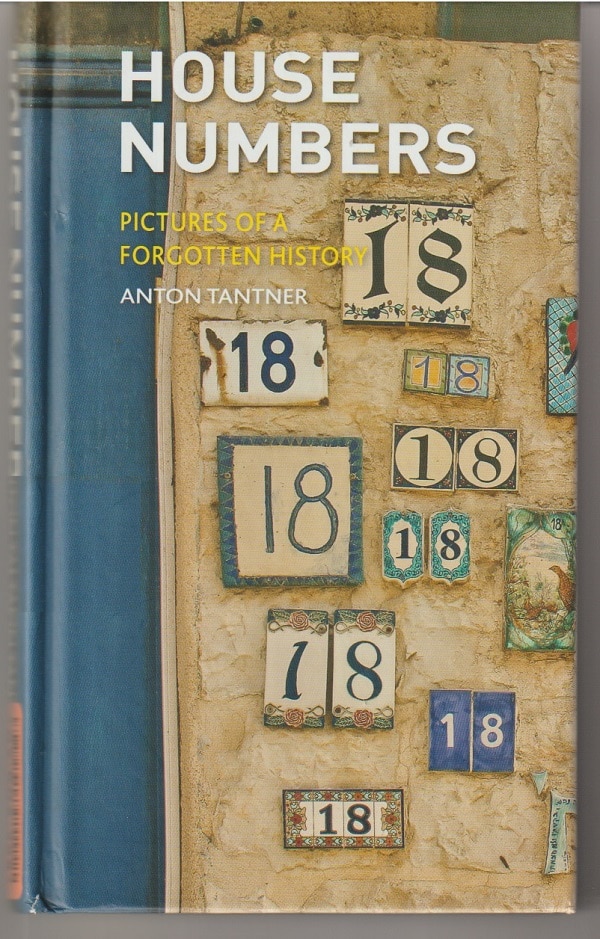

This array of many versions of the same house number is in Jerusalem. In Hebrew, the number 18 is auspicious be cause of its relationship with the word that means life.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.14.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.