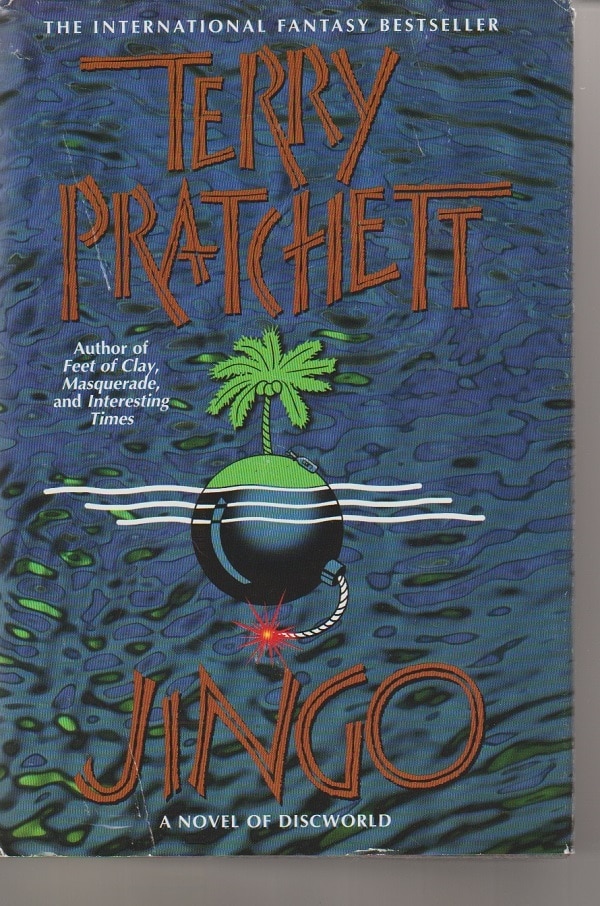

Midway through Terry Pratchett’s 1997 novel Jingo, a conversation takes place between Captain Carrot Ironfoundersson and Corporal Delphine Angua von Überwald.

He is a 6’6” dwarf (by adoption) who’s the second-in-command of the Ankh-Morpork City Watch and, deeply and fully, the quintessence of honor and truth. Indeed, he is one of those rare, pure personalities who thinks the best of everyone and expects the best of everyone and, through this purity and trust, is usually able to elicit from everyone their best.

She is a beautiful woman and an on-the-wagon werewolf who is a bit more skeptical of her fellow creatures, perhaps because, regularly, she turns into a fairly wild animal.

Carrot and Angua are lovers.

At this moment in their exchange — which occurs in the room of a dead man who was not just a murderer but also a murderee — Angua steps back figuratively into her head to consider her relationship with Carrot:

Technically, Angua was sure she knew Carrot better than anyone else. She was pretty sure he cared a lot for her. He seldom said so, he just assumed she knew. She’d known other men, although turning into a wolf for part of the month was one of those little flaws that could put any normal man off and, up until Carrot, always had. And she knew the sort of things men said in what might be called the heat of the moment and then forgot.

Carrot, though, she realizes, is quite different:

But when Carrot said things, you knew that he felt that everything was now settled until further notice, so if she made any comment he’d be genuinely surprised that she’d forgotten what it was he had said and would probably quote date and time.

And yet all the time there was this feeling that the greater part of him was always deep, deep inside, looking out. No one could be so simple, no one could be so creatively dumb, without being very intelligent.

“His legacy”

I enjoy seeing Carrot and Angua show up in one of Pratchett’s books. They’re vibrant characters on their own and doubly vital together.

However, as I was reading these few pages of Jingo about their conversation, I came to the melancholy realization that Carrot and Angua will have no new adventures. That future was cut off in 2015 when Pratchett, the victim of early onset Alzheimer’s, died at the age of 66.

I am about midway through a re-reading of the 41 Discworld novels. I know that, as I move through the series, I’ll see the two of them again. And, yes, they will continue to live on as long as anyone is reading — and laughing with — one of Pratchett’s numerous books about the two characters and the rest of the City Watch.

Even so, the mournful truth is that, when an author dies, so die any potential future the author’s characters might have had.

After Pratchett’s death, his daughter Rhianna told the Guardian that there would not be any new Discworld novels. “The books are sacred to dad,” she wrote on Twitter. “That’s it. Discworld is his legacy.” And, to underline the point, she said: “To reiterate — no, I don’t intend on writing more Discworld novels, or giving anyone else permission to do so.”

Although that means no more new Carrot and Angua stories, I’m glad of this. There’s something sad and hollow when another writer, always a lesser writer, tries to “continue” the characters of a dead author. Huck Finn, by anyone other that Mark Twain, ain’t Huck Finn.

Armies under arrest

I interviewed Pratchett back in 2000 when I was a reporter for the Chicago Tribune and he was on a book tour to promote his latest Discworld novel The Fifth Elephant.

He was a short, gnomish man with a lisp and a grizzled white beard who radiated wonder, delight and intelligence. We sat in a hotel lobby and talked a lot about religion, a central issue in that then-new novel.

Pratchett used his novels as vehicles for examining the full range of human oddity, a subject that filled him with enormous fascination, fondness and abhorrence.

In Jingo, he takes aim at war and patriotism, and the result is a comic opera story in which two entire armies are put under arrest and a butler bites off the nose of an opponent.

“Seventeen ears”

The heart of the story, though, comes near the end when Commander Sam Vimes of the City Watch — the guy who arrests the two armies — is recalling, not very happily, the war stories that, as a child, he’d hear former soldiers tell:

What he remembered most, among the descriptions of puddles filled with blood and flying limbs, was the time one old man said, “An’ if your foot caught in something, it was always best not to look and see what it was, if’n you wanted to hold on to your dinner.”

He’d never explained what that meant. The other old men seemed to know. Anyway, nothing could have been worse than the explanations Vimes thought of for himself.

And he remembered that the three old men who spent most of their days sitting on a bench in the sun had, between them, five arms, five eyes, four and a half legs and two and three-quarter faces. And seventeen ears (Crazy Winston would bring out his collection for a good boy who looked suitably frightened).

Poignancy and a zinger

That was Pratchett: He’d make his point with evocative poignancy — and then finish with a zinger to draw a laugh.

He loved people. And he knew how confused, unprotected and afraid we all are.

With his death, we not only lost any future stories with Carrot, Angua and the other Discworld characters.

Even more, we lost his voice of sanity amid the human tendency to insanity, his amazement and affection for everyone who is flawed — which is all of us — and his Olympian anger against those who play games with our frailty and fear for their own devious purposes.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.13.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.