The odds are that you don’t have a copy of the Jewish War by Josephus in your book collection. You may never have heard of it. It was written around 75 A.D. as a work of history by a Romanized Jew, but it has been employed in various ways over the past two millenniums by two great world faiths as a sort of pseudo-scripture.

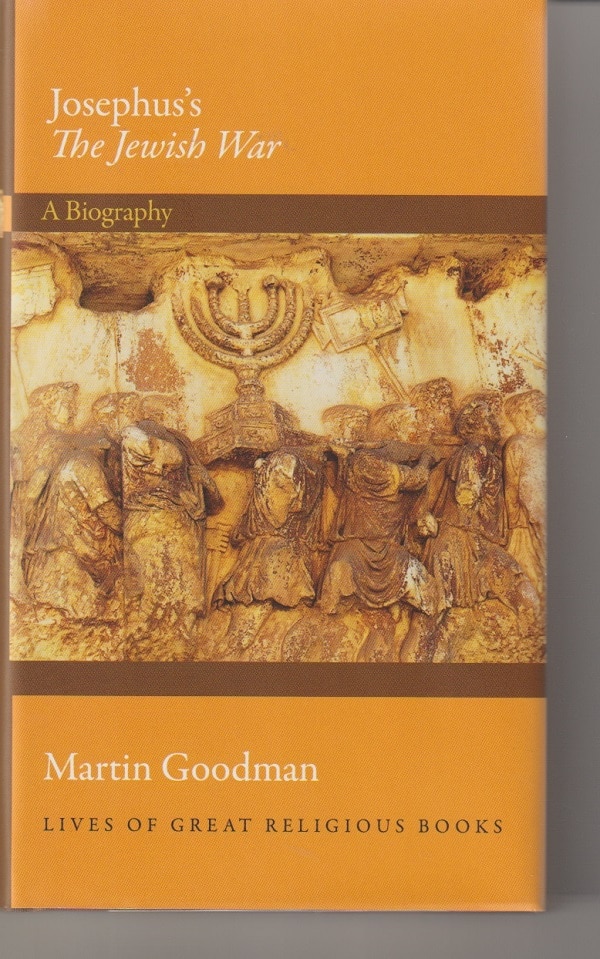

Indeed, the life story of that work — Josephus’ ‘The Jewish War’ by Martin Goodman — has just been published by Princeton University Press as part of its spry and sparkling series Lives of Great Religious Books.

And, as Goodman notes in his preface, everyday American and English people back in the 19th century were quite familiar with the Jewish War, often putting a beautifully bound copy of its English translation by William Whiston on the shelf next to the Bible. And writers would routinely drop in a mention of the work. For instance, in Captains Courageous (1897), Rudyard Kipling portrays American fisherman reading on Sundays from

“the book called ‘Josephus,’ an old leather-bound volume, smelling of a hundred voyages, very solid and very like the Bible, but enlivened with accounts of battles and sieges.”

In his 1886 novel The Mayor of Casterbridge, Thomas Hardy writes of a folio of Josephus on the mayor’s dining room table. Four years later, Mark Twain, in his travelogue Roughing It, notes cheerfully:

“I felt rowdyish and ‘bully,’ (as the historian Josephus phrases it, in his fine chapter upon the destruction of the Temple).”

Divine inspiration

Josephus, born in 37 A.D., the descendant of a line of priests, was a diplomat and general during the Jewish rebellion against the Roman occupiers, the conflict that was the subject of his Jewish War.

At the age of 29, he was assigned to lead troops defending Galilee, troops that were no match for the Roman legions under Vespasian. Josephus and some of his soldiers, caught inside a cave, vowed to commit suicide rather than capitulate. However, when only he and one other remained alive, Josephus decided — through divine inspiration, he writes — to surrender.

At the age of 29, he was assigned to lead troops defending Galilee, troops that were no match for the Roman legions under Vespasian. Josephus and some of his soldiers, caught inside a cave, vowed to commit suicide rather than capitulate. However, when only he and one other remained alive, Josephus decided — through divine inspiration, he writes — to surrender.

Dragged before Vespasian, Josephus did something else that he wrote was a message from God — he announced the highly unlikely prophecy that the humbly born Roman general would become the Emperor.

Nonetheless, the prediction came true just two years later in 69 A.D. when Vespasian was able to take advantage of civil unrest across the empire to wrest for himself supreme power. Josephus was freed and became a member of the entourage of the new Emperor and his son Titus. And he was with Titus a year later when the son besieged Jerusalem and then destroyed it.

Soon, Josephus was in Rome, a citizen and landowner, who spent the rest of his life — about 30 years — writing.

Three reasons

Josephus has been famous ever since — at least, in an inside-baseball way — for three reasons.

First, in his book Jewish Antiquities — the story of the Jews from creation to just before the outbreak of the rebellion against the Romans — Josephus may or may not have mentioned Jesus Christ as an historical figure. Scholars hotly debate whether Josephus included two references to Jesus that are now in the work or whether one or both were Christian interpolations. Much more accepted is the reference in the book to John the Baptist. (In Josephus’ ‘The Jewish War,’ Goodman mentions this only in passing.)

Second, the Jewish War is the source for the controversial account of the mass suicide of Jewish soldiers in the large mountaintop fortress of Masada — a story that, throughout history, has been seen by some Jews as heroism in the face of oppression and by others as stubborn extremism.

Third, the Jewish War is the best and most complete chronicle of what’s now known as the First Jewish-Roman War (66–73 A.D.) which culminated in the burning of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple, the focal point of Jewish worship, one of the most traumatic events in Jewish history. Josephus, an eyewitness, wrote his history just two years after the end of the war.

Experts and non-experts

Josephus has been famous to religious scholars and leaders, both Jewish and Christian, down the last 1,900 years. He’s been important to regular folk because those specialists used his writing to shape what they taught to the non-experts.

In his energetic and nuanced look at the Jewish War in history, Goodman notes that, while many English-speaking homes in the 1800s had copies of the work, “How many owners of those bound volumes found their way actually to read what Josephus wrote is another question.”

For specialists, though, Josephus hasn’t just been famous. He and his works have been, as Goodwin shows, a constant bone of contention although the particular reasons for dispute have shifted wildly from one era to the next.

“At the feet of the strangler”

For instance, early Christians used the Jewish War to interpret the fall of Jerusalem and the Temple as payment for the sin of crucifying Jesus. Later, during the Renaissance, Josephus was seen as a humanist role model.

Meanwhile, Jewish authorities ignored the book for hundreds of years, and, even then, it entered the canon of rabbinic literature through a Hebrew book, known as Sefer Yosippon. This history of the Jews told the story of the destruction of the Temple by adapting another work that itself was a paraphrase of the Jewish War.

In the last two centuries, debates have ranged over the character of Josephus, some seeing him as a coward and a traitor while others believing him a realist.

For instance, Protestant theologian Edward Reuss, although empathetic toward the Romanized Jew, wrote:

“A patriot, a true Pharisee, in the good sense of the word, would never have laid down the eternal hopes of his people at the feet of the strangler of his fatherland. This one action, which he recounts with cynical smugness, without feeling any shame,…reveals a lack of character, which might hold the key to Josephus’ actions and writings.”

However, a Jewish periodical in Germany described Josephus as “a pious and God-fearing person” who, writes Goodman, was “close to the ideal ‘New Jew’ envisaged by the members of the Hebrew Enlightenment.”

“Almost instant history”

Goodman believes it is “rather bizarre that Josephus has so often been judged as a cowardly traitor to his people.” He acknowledges that the writer had to work within the Roman power structure which put limits on what he could relate and how he could relate it.

“But it cannot be denied that his decision to write so copiously and positively about the Jewish tradition was itself an act of exceptional bravery in a world where it was often safer to say nothing at all.”

Later, Goodman acknowledges that the Jewish War isn’t a great work of literature in terms of style and structure. Nonetheless, he writes:

“The Jewish War was a fine work of almost instant history composed in the immediate aftermath of a dramatic campaign of great political significance not just for the Jews by for the whole Roman world.”

Patrick T. Reardon

12.9.19

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.