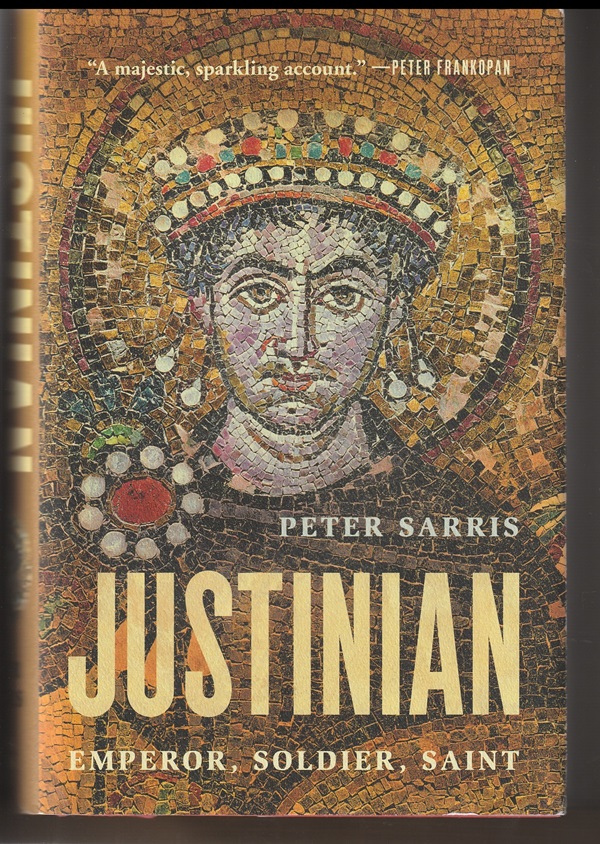

John, the friend who recommended Peter Sarris’s 2023 Justinian: Emperor, Soldier, Saint, had one caveat about the book’s subtitle: “He was no saint.”

It’s funny how a comment like that will stick with me. So, as I was reading this fine, thorough and revealing biography, I was primed to think about whether the subtitle was, as is usual in today’s publishing world, overstating the case or whether there might be some substance there, despite John’s skepticism.

And it wasn’t only the “saint” part of the subtitle. I wondered too whether Justinian was that much of a soldier.

By contrast, there was no question that Justinian was the Roman emperor, headquartered in Constantinople for 38 years, from 527 to 565. And no question that, in that position, he had a major impact in his own time and down the centuries on civic law in the east and west, on the evolution of Islam, on the dogma of the Catholic Church and even on the primacy of the Pope as the Bishop of Rome.

Two different subtitles

Pretty early in my reading of Justinian, I came to the conclusion that John was right that “saint” was somewhat hyperbolic and also “soldier.”

Justinian was without question the commander-in-chief, directing armies in the east to blunt intrusions by Persia and various invading tribes such as Huns and in the west to reconquer great swaths of former Roman territories in Africa, Sicily, Italy and Spain. But his was soldiering done at a distance.

And Sarris doesn’t present much to argue for the emperor’s holiness, even as he extensively details the way Justinian worked ceaselessly to unify the Christian believers of his era behind the one set of doctrines.

The subtitle I came up with was Emperor, Commander, Theologian.

But, in the final chapters of the book, the strong criticisms of Procopius, one of the great writers of Justinian’s era, made me think that, if this critic had come up with the subtitle, it would have been Tyrant, Megalomaniac, Demon.

“Bloodlust and greed”

Procopius’s criticisms of Justinian are harsh to the extreme.

Procopius’s criticisms of Justinian are harsh to the extreme.

Sarris writes that Procopius depicts the emperor as “hell-bent on transforming [the empire] into an instrument of his own tyranny, driven primarily by bloodlust and greed,” while lambasting his wife Theodora, something of a co-ruler, for “her cruelty — and in highly graphic terms — her supposed sexual excess prior to her childless marriage to Justinian.”

Indeed, Propocius argues that Justinian was everything an emperor should not be:

Justinian was vulgar instead of noble, he said, capricious instead of just, and as close to Satan as he claimed to be close to God.

Theodora…was for Procopius the inversion of the ideal Roman matron, sexually immodest instead of chaste, and murderous instead of maternal.

What’s striking is that Procopius is quoted throughout Sarris’s book, but the author doesn’t bring up these severe judgements until more than three-quarters of the way into the biography — until just before he recounts Justinian’s death.

Justinian’s career

This appears to have been a conscious decision on Sarris’s part.

His book, up until this point, details Justinian’s career on the throne in the work he carried out:

- His extensive codification and promulgation of laws.

- His generally successful efforts to cajole, bully and manipulate religious leaders to find agreement on a key doctrinal question on the nature of Jesus Christ.

- His moves to put down a rebellion of the poor of Constantinople (and their rich backers).

- His efforts to deal with the trio of disasters that befell his reign: climate change and the poor harvests that resulted, and the bubonic plague that, it seems, spread faster and more extensively because of the climate change and the poor harvests.

- His military moves to keep eastern foes at bay while also winning huge areas of the empire in the west, particularly Rome.

“Unmatched intensity”

Justinian “pursued these policies with unmatched intensity and determination, harnessing the talent of his generals in the field and his advisors at court,” writes Sarris.

Under this patronage, we see the last (and perhaps greatest) efflorescence of Roman legal thought, and a brilliant distillation of a thousand years of jurisprudence which would determine the form in which Roman legal culture would be transmitted to posterity, not only within the empire but far beyond.

The emperor also stimulated and contributed to one of the most creative moments in the history of Christian religious thinking, drawing upon the rich intellectual heritage of the Greek philosophical tradition to give greater conceptual complexity and nuance to the faith, and defining how Christian orthodoxy would be received in the Middle Ages to both East and West.

“One of the finest historians”

In addressing all of these aspects of Justinian’s reign, one of Sarris’s chief sources is Procopius, particularly his eight-volume History of the Wars.

Procopius modeled that military history on the work of Thucydides, Herodotus, Plutarch and other classic writers, and later historians have viewed him as “a towering figure.” Sarris writes:

In the late sixth century, the diplomatic historian Menander would praise what he described as the “eternal light” of Procopius, who to this day is regarded by many as one of the finest historians ever to have written in the Greek language.

Which goes a long way toward explaining the amazement that greeted the discovery, in 1623, of another book by Procopius — the Secret History which contains his criticisms of Justinian.

Sarris notes that, although not written with as much style as his History of the Wars, the book was a “tour de force,” going on to add:

The Secret History is unlike any other literary work that survives from the ancient world. It brilliantly turns imperial propaganda on its head and uses it as a stick with which to beat the emperor.

Sarris doesn’t mention the Secret History until this late in his book because, as he later explains, this brilliant work of anti-propaganda has long overshadowed Justinian’s reputation. It seems clear that Sarris waited to bring these criticisms to the reader until he had had a chance to lay out the many accomplishments that the emperor achieved and challenges he faced.

“The superstition of a monk”

In the epilogue of Justinian: Emperor, Soldier, Saint, Sarris writes that, for the last four centuries, ever since Secret History was re-discovered, the western view of the emperor has been shaped by Procopius.

For Montesquieu, the 18th century French philosopher, Sarris writes, Justinian “was the epitome of oriental despotism: a tyrant and bigot, dominated by his wife, and wracked with jealousy directed at [one of his generals].”

Edward Gibbon, the late-18th century English historian and author of the six-volume The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, declared that Justinian “was regulated not by the prudence of a philosopher, but the superstition of a monk.”

Sarris, though, argues that such luminaries have been blinded by the literary light of Procopius. Justinian’s reign, he writes, was one “of remarkable achievement, creativity, and reform.”

“A fundamental contribution”

Historians, he asserts, have over-emphasized Procopius’s critiques because the emperor’s military accomplishments were short-lived. In doing so, they missed the true impact of Justinian:

From the start, what had mattered most to the emperor had been the definition of “orthodoxy” and reform of the law. In these two spheres of activity his accomplishments would endure….

Indeed, Sarris argues that the emperor should be judged by “the remarkable extent to which Justinian’s influence has been felt across the world in societies both East and West, in the 1,500 years that have passed since he first ascended the throne of Constantinople as sole emperor on that day in August of 527.”

And he concludes:

Whether viewed as a holy emperor or a demon king, as soldier or saint, Justinian made a fundamental contribution to the world in which we live today, and his legacy is still with us.

Patrick T. Reardon

12.5.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.