Armand Degas — a middle-aged Ojibway-French Canadian, also known as Blackbird, also known to his increasing irritation as Bird — waits for another chicken pot pie to bake while Donna clears the table and tidies up the kitchen.

Donna Mulry is a 50-year-old former prison guard who has been providing a home and her bed for Richie Nix, a much younger ex-con who, through circumstances, is Armand’s temporary partner. Her house is in Marine City, Michigan, a rural town northeast of Detroit and across the St. Clair River from the Canadian province of Ontario.

As Richie watches TV in the living room, Armand waits for his second pot pie and Donna talks about this and that, including one of her theories about Elvis:

“If Elvis was Jesus, you know who I think some of his apostles would be? I think Engelbert would be one. I think Tom Jones would be one. And I think, going way back, the Jordanaires and the Blackwood Brothers. Who do you think?”

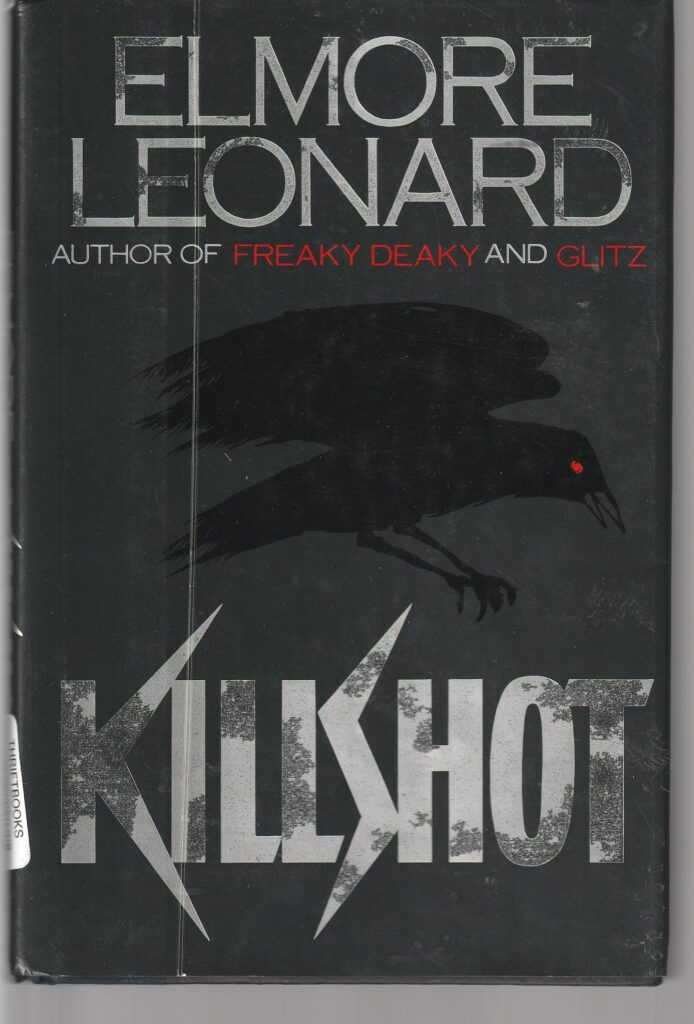

This is one of those wacky, wonderful moments that come often in an Elmore Leonard novel, rich with the goofiness of humanity. Killshot, published in 1989, has a lot of them.

Donna is not a complete fool, but, like all of us, she has her blind spots.

As Armand listens, Donna goes on to explain that the memory of Elvis is like a magnet pulling her to Memphis. She says, if she lived there, she’d visit Graceland every day “the way people visit a church and light candles to get their burdens lifted or find a boyfriend.” It would be, she says, worth the $7 admission fee each day.

Armand said, “I believe you,” because he could see be believed it herself.

Armand has no interest in Elvis, but he’s trying to be a nice guy.

Which is swell, except….

Just everyday guys

Here’s the thing: Some of Donna’s blind spots are more dangerous than, say, her yearning for Elvis more than a decade after his death.

Richie isn’t just an ex-con, but he’s a guy who’s made a career as an armed robber and who, recently, has been developing a habit of killing people with a shot to the face for no real reason except he kinda feels like it. He kills people for fun.

Armand, on the other hand, kills people for pay. Such as a mob boss and the boss’s girlfriend at the opening of Leonard’s novel. It’s just a job, and he does it.

Donna could find a lot of this out if she wanted to, but she has enjoyed having Richie around to baby and now likes Armand as someone to listen to her and take her to bed when the young man is away.

The domestic scenes of these two sociopaths in Donna’s house are quintessential Leonard. They’re just guys, as everyday as you or as me.

Except, of course, the reader also knows what they’re capable of.

“Maniacs”

Toward the end of the novel, Carmen Colson, a 38-year-old would-be real estate agent, is being held captive by Richie and Armand as they wait for her steelworker husband Wayne, 41, to walk blissfully ignorant into their trap. They are going to kill both Colsons.

Carmen is trying to remember where Wayne — who likes deer hunting — put the couple’s shotgun. To help her get through this, she’s picturing him in her mind, talking to her.

She asks him if he’s scared and he says, for Christ’s sake of course he’s scared, you’d have to have brain damage not to be scared of these assholes.

Don’t let their chitchat, that casual bullshit, fool you, these guys are fucking maniacs.

That about says it all, for Killshoot and for most Elmore Leonard novels. Sociopaths, like Richie and Armand, are human beings. They can be gracious and attentive and catty and annoying and endearing.

But they kill people.

Clever. And lucky.

In a Leonard novel, it’s fun to see such bad guys as just guys, but you also know that, at some point, often in a fairly unexpected moment, they will let their sociopathology have its full reign.

That’s what happens in Killshoot.

But Wayne and Carmen — who got in this trouble by being at the wrong place at the wrong time — are resourceful and, yes, not at all crazy. They turn out to be pretty clever. And lucky, too.

One hint: Remember I mentioned that Armand is getting irritated at being called Bird. Richie is the one who was calling him Bird.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.7.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.