Less than two years ago, novelist Salman Rushdie was the victim of a stabbing attack that left him near death.

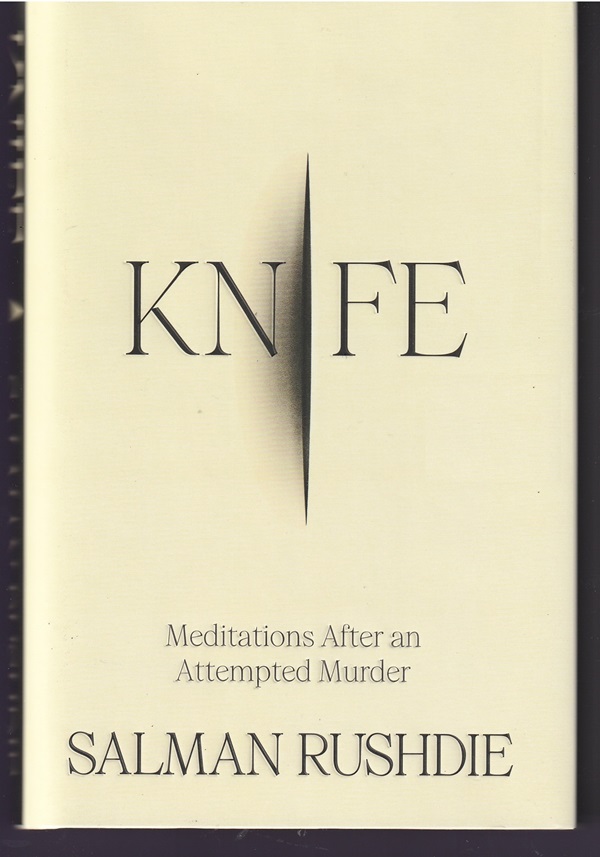

His newly published nonfiction book Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder is an effort to come to grips with that violence and, in a way, to gain control of what happened to him.

Writers write to understand life — their own and the life of all humankind — and to take the chaos of every day and package it, to give it form and make it comprehensible. Herman Melville wrote Moby Dick as a way of coming to grips with obsession. Jane Austen wrote Emma as a way of figuring out romance and marriage.

Knife, Rushdie writes, is a book “I’d much rather not have needed to write.” However, as he was recovering from the 15 knife wounds he suffered and was trying to get back to work on his next project of fiction, he found that the attack was something like an elephant in the room — “a fucking enormous mastodon in my workroom, waving its trunk and snorting and stinking quite a bit.” And a creature that needed to be reckoned with.

This book is that reckoning. I tell myself it’s my way of taking ownership of what happened, making it mine — making it my work. Which is a thing I know how to do. Dealing with a murder attack is not a thing I know how to do. A book about an attempted murder might be a way for the almost-murderee to come to grips with the event.

The A

For more than thirty years, the Indian-born Rushdie lived under threat of sudden death after the Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini — angry about the depiction of Islam in his novel The Satanic Verses — issued in 1989 a fatwa calling for his assassination with a bounty of $3 million.

Rushdie, who had become a British citizen in 1964, lived in hiding for many years as police and other security forces were able to discover and block several serious plots against him. However, he ventured more into public after moving to New York in 2000. He became an American citizen in 2016.

Rushdie, who had become a British citizen in 1964, lived in hiding for many years as police and other security forces were able to discover and block several serious plots against him. However, he ventured more into public after moving to New York in 2000. He became an American citizen in 2016.

On August 12, 2022, Rushdie was about to give a public lecture at the Chautauqua Institution in Chautauqua, New York, when a young man dressed in black raced up the aisle to slam a knife into him over and over again. A 24-year-old New Jersey man named Hadi Matar was wrestled to the floor and later charged with assault and attempted murder.

In Knife, Rushdie goes out of his way to avoid mentioning Matar’s name:

I do not want to use his name in this account. My Assailant, my would-be assassin, the Asinine man who made Assumptions about me, and with whom I had a near-lethal Assignation…I have found myself thinking of him, perhaps forgivably, as an Ass. However, for the purposes of this text, I will refer to him more decorously as “the A.” What I call him in the privacy of my home is my business.

Antithesis

That bit of word play is one of the rare moments in Knife in which Rushdie’s vibrant and playful storytelling is on display. Of course, there’s not much about the attack and his long recovery, including the loss of his left eye, that could be considered playful.

Knife, in many ways, is the antithesis of Rushdie’s fiction. Instead of imaginative flights of fancy and fantasy and trenchant insights about the way people go about being people, this book is reportage.

Reporting on what his body and psyche went through in and after the attack, Rushdie is clear and observant and open about how it all felt and what he thought. He is the rare victim of violent trauma to have the intelligence, experience and high-level literary talent to tell a story of shock, suffering, pain and rehabilitation with such clarity and fullness.

It is striking to recognize that what he went through is what, to one extent or another, every victim of violence goes through. It is his personal story, but one can imagine every other victim going through many of the same experiences and same feelings.

Knife is Rushdie’s testament, and it can be seen, in a way, as a testament for all victims of violence.

“Take ownership”

Which is somewhat odd.

One would think that a book by Salman Rushdie would be something very different from what anyone else might write. Knife, though, sticks closely to the attack and the rehabilitation. It doesn’t go far afield.

Knife, according to its subtitle, is made up of meditations. Yet, aside from some almost pro forma mentions of the need for writers to be free to write what they want, Rushdie doesn’t use his experience to think about broader questions. I suspect that such pondering is going on and will show up later in his fiction.

For this book, he exhibits a laser focus on the facts and details of what happened to him.

Knife is an interesting book to the extent that it gives the reader an insight into what Rushdie went through — into what the victim of violence goes through. In a sense, it could have been written by any victim of violence.

Knife isn’t a book that was written, like Rushdie’s fiction, to entertain readers, to get them thinking about the way people are and how they act, to play word games with readers and dazzle them with unexpected beauty and pungent descriptions.

It is a book that Rushdie wrote to exorcise his demons. To “take ownership” of what happened to him. And to clear the way for whatever he’s going to write next.

And I’ll bet it’ll be a book that he has some fun with.

Patrick T. Reardon

5.15.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.