Normally, I’d just as soon know little or nothing about the author of a novel I’m reading. Later, after the book’s done, yeah, maybe I’ll try to find out some information, but, really, it’s the book that counts.

However, Ed McBain wanted to have his say, and I found myself listening.

What happened is that, in the early 1990s, Otto Prenzler Books decided to publish in hardcover editions the first seven books in McBain’s 87th Precinct novels as part of its Armchair Detective Library. All seven started life as paperback originals in 1956-1958 when the series was envisioned as little more than pulp books and when expectations were low.

But McBain could really write, and the 87th Street Precinct novels quickly found an audience that just kept growing. Indeed, by 2005, the series had grown to 53 books.

The eighth novel, Killer’s Wedge, was published in January, 1959, in both hardcover and paperback as were every other new book in the series after that. But the first seven weren’t available in hardback until published by Prenzler Books. It started in 1990 with Cop Hater, the first of the series, and the seventh, Lady Killer, came in 1994.

To boost interest among fans of the series, McBain wrote an introduction or an afterword for each books, explaining some aspect of how it came to be written the way it was written. Mainly, he used these to complain and get revenge on the powers-that-were at his original publisher.

“A mere human being”

The thing was that those powers-that-were had ideas about how McBain should develop the series. The writer had his own ideas, and they didn’t mesh with all the suggestions he was getting from the higher-ups.

For one thing, as he explains in his commentary on an earlier book, he killed off one of the detectives in a manuscript he turned in, but his publisher refused to permit that because the deceased detective was considered, as McBain put it, the *S*T*A*R* of the series. Hence, a dead shot became a near miss.

So, McBain groused about that, and, in the introduction to Lady Killer, he groused about another publisher plan to make a new member of the squad, Cotton Hawes, another *S*T*A*R*. Ah, but McBain won this battle, as he explains:

Speaking of Cotton, you’ll notice that in this book I simply had no time to fool around with making Hawes a big *S*T*A*R*, the way a misguided publishing person had earlier insisted. Instead, he becomes a mere human being, an integral part of other humans in the repertory company of cops. I like him better this way.

“Driven by a single plot”

When McBain writes that “I simply had no time,” that’s because, as he’s already explained, he wrote Lady Killer in nine days in the summer of 1957 while on vacation in Martha’s Vineyard with his family. Twenty pages a day = 180 in the manuscript which was what he was expected — and all he was permitted — to write. (That comes out to about 157 pages in the printed book.)

So, he was cranking out these pages at a typewriter in the garage, and he explains:

Because I was driven by a singular need to get onto the beach as soon as possible, the book itself is driven by a single plot. It’s a no-frills book…And because it was written fast, it seems to move fast.

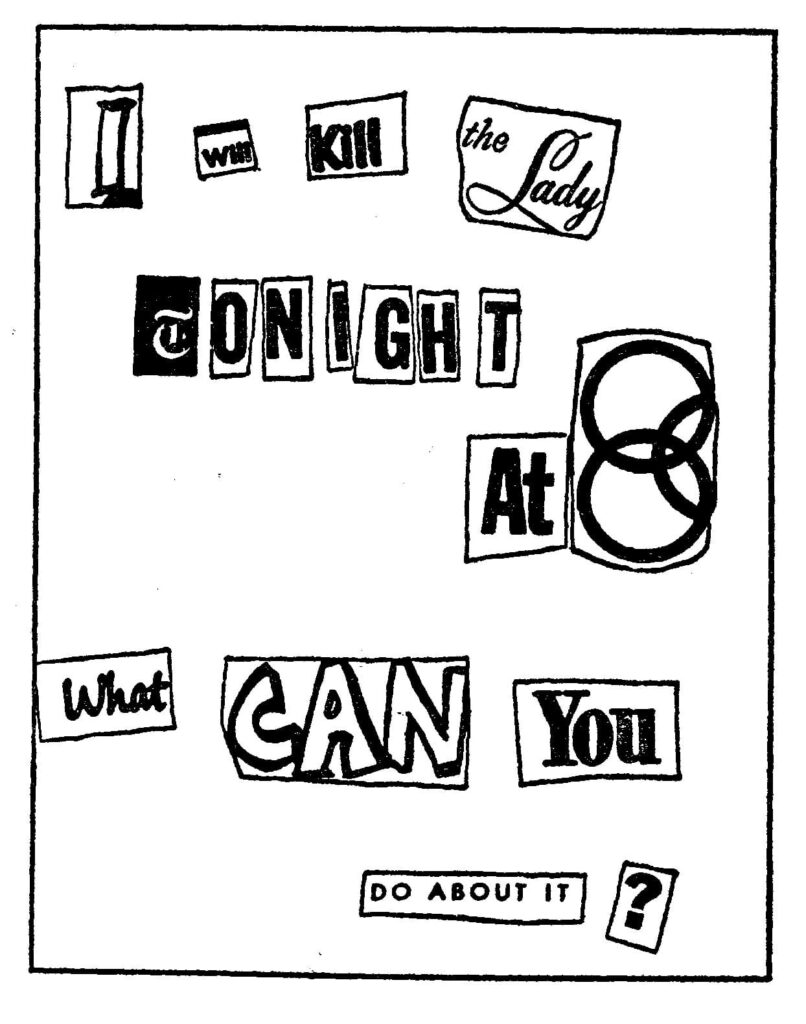

Like McBain, the detectives in the squad are also operating on a time clock. The book starts with this letter delivered to the police station:

The letter arrives around 8 a.m. on July 24, 1957, and it means the detectives have 12 hours to find the guy who is planning to kill “the Lady” but who also seems to want to get caught, maybe.

Clipping the New York Times

I suspect it would be a fun exercise for a lit-crit major at some university to analyze how McBain’s self-imposed deadline impacted the writing of his book.

I have a few observations along those lines because, primed by the author’s introduction, I was looking for how the book I was reading might be reflecting how the writing was taking place — in other words, for a glimpse into McBain’s writing process.

For instance, the police lab studied the note in a variety of ways and was able to report:

“He used the magazine section and the book section of the [New York] Times for Sunday, June twenty-third. We’ve located enough of the words he’s used to eliminate coincidence. For example, The Lady came from the book section. Snipped from an ad for the Conrad Richter novel. The word can was from an ad in the magazine section for Scandale. That’s a woman’s undergarment trade name…

“The figure eight was obvious, again from the magazine section. An ad for Ballantine beer…The word kill was easy. Not many advertisers use that word unless it’s pertinent to their product. This ad said something about killing bathroom odors.”

Absolutely right and not quite right

This gave me the idea that, early on in those nine days of banging away at his typewriter, McBain took a break to grab a recent copy of the New York Times to do the cutting and pasting to create the letter from the killer.

I was absolutely right and not quite right.

Essentially every page that has been published in the Times since 1851 is available online to subscribers, so I got the issue for June 23, 1957, and went looking for the pieces of the killer’s note.

Sure enough, there was the brand name Scandale from which the can of the note came, and there was kill in the ad for Florient air spray from Colgate with the headline, “Kill bathroom odors fast…” In both cases, the font and size were perfect.

Ah, but that wasn’t the case for the Lady and the figure eight. Yes, in the Times book section, there was an ad for Richter’s novel but the typeface and size were different from that in the note to the cops. Similarly, there was an ad for Ballantine beer, but the only figure eight design in the ad was a teeny, tiny image on a small drawing of a Ballantine bottle.

I’m not sure what happened. I suspect McBain created the note from that Times edition and later changed some of the words for one reason or another.

“A train of events”

McBain was right when he wrote in his introduction that his book moved fast. There are shootings and tussles and a chase across rooftops as well as the comedy of dozens of boys in red-striped t-shirts being brought to the squad room in a search for the one who carried the killer’s note into the police station.

The momentum of the search for the killer — and the effort to identify the victim — gets fast and heavy, and, then, McBain plays a writerly card: He slows everything to a halt.

This is a device that authors use. While it seems to slow the story down, it results in an increasing level of tension.

The 87th Precinct detectives have only until 8 p.m. to stop the killer, but, at 5:15, all hell breaks loose in the station and doesn’t calm down until 6:05, leaving less than two hours to complete the hunt.

It started with the fat woman in the housedress, and her arrival at the slatted rail divider seemed to trip off a train of events none of which had any immediate bearing on the case. It was terribly unfortunate that the events intruded upon the smooth progress of the investigation.

Those events included the housedress woman complaining loudly that her son in a red-striped t-shirt had been questioned, and a drug pusher who’d been beaten bloody over the head by the husband of his girlfriend, and the husband swinging wildly with his fists at Cotton Hawes and then attempting to bribe him with $500 (the equivalent of about $5,000 today), and a jewelry store robber.

One day’s writing

As I said, this is a device authors use to keep the reader in limbo while eagerly awaiting the plot to get in motion.

However, because of McBain’s introduction, I had another thought.

I pictured him cranking out pages day after day, and, by the end of the seventh day, he’s got 119 pages of book as it would be eventually printed. But he’s still a lot short of what he needs — about 38 more pages in the published book — and the cops have gotten very close to grabbing or missing the killer by the 8 p.m. deadline.

So, what happens on page 119 in the published book? You guessed it, all hell breaks loose with the housedress woman and the jewel thief and all the others, and the description of that 50-minute break takes 13 pages. Which is about one day’s writing.

So, it seems to me that McBain, when he saw the end coming too fast, he took his eighth day of writing to get this interruption of the story down and fill the pages he needed to fill and set things up so that, in his final day of writing, he could pick up where he’d left off.

It works well. Lady Killer is a dandy little novel. And it’s just the right length, no matter what McBain’s reason for those interruptions in the investigation.

Patrick T. Reardon

4.27.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.