For African Americans who took part in the Great Migration in the first half of the 20th century, the North was a Land of Hope that often disappointed.

Some important aspects of life were better than back in the South, greater political and social equality and greater employment opportunities. But much of life in northern cities was tainted by racism, such as way that White Chicagoans used laws, institutions and violence to keep Blacks hemmed into segregated neighborhoods — the Black Belt on the South Side and a smaller enclave on the West Side.

The housing in these communities was often run-down and further worn down by overcrowding. In one essay, Richard Wright called Chicago “that great iron city,” and it wasn’t a compliment. In his novel Native Son, he wrote that Black Chicagoans were immersed in a “huge, roaring, dirty, noisy, raw, stark, brutal” city.

Brian McCammack, an assistant professor of environmental studies at Lake Forest College, quotes Wright in Landscapes of Hope: Nature and the Great Migration in Chicago and adds these words from an interview with two siblings who took part in the Great Migration, Clarice Durham and Charles Davis:

“[I]n Chicago, there was not that smell of nature. You’d smell, you know, the horse leavings, the exhaust from cars, and that sort of thing. But not the pleasant smells.”

In the South, African Americans had lived close to nature. In Chicago, they were in a land of concrete, bricks, steel, glass and garbage. As a result, they yearned for connection with natural rhythms and the natural landscapes — and did what they could to find green space and green places. McCammack writes:

“Black Chicagoans fostered relationships with nature in a wide range of sometimes unexpected places, often well beyond the commonly understood historical and cultural geography of the city’s Black Belt.”

“Landscapes of hope”

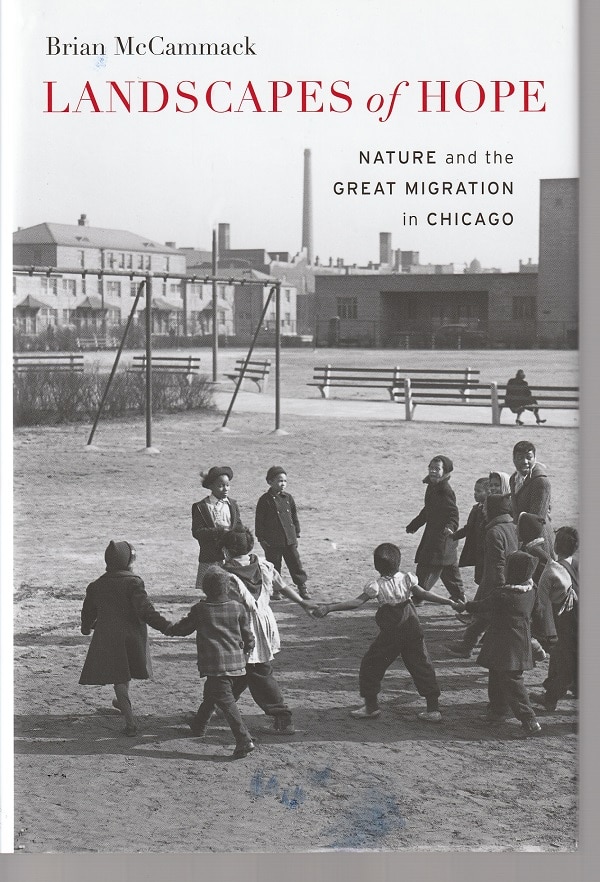

Those relationships are the subject of McCammack’s book, originally published in hardcover in 2017 and now available in paperback. And the places where African Americans found nature — which McCammack calls “landscapes of hope” — included:

- The 371-acre Washington Park, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, at 51st Street and Grand Boulevard (now Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive).

- The 10-acre Madden Park constructed with New Deal funding at 38th Street.

- The beaches along Lake Michigan at 31st Street and at Jackson Park.

- Resort towns in Michigan, such as Idlewild.

- Youth camps, including the YMCA’s Camp Wabash.

- The Cook County Forest Preserves.

- The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps in rural Midwest marshes, farmlands and forests.

McCammack writes that the importance of nature to African Americans who had moved from or had strong ties with the rural South has been overlooked in the past, and he asserts:

“Appreciating the many ways that these natural and landscaped environments held meaning for Black Chicagoans yields a deeper, richer, and more complex account of African American life during the first wave of the Great Migration, presenting a fresh perspective on what it meant for Southern migrants to adapt to urban metropolises.”

Such natural and landscaped environments were as important to Black Chicagoans as the Stroll, the Black Belt’s entertainment district, McCammack writes, noting that they provided a sharp contrast to the everyday urban world in which African Americans lived:

“They were greener and more alive — with plants and animals, if not with the people and excitement that the Stroll boasted. They smelled different, and they were often quieter and cooler on hot summer evenings than the South Side’s built environment.

“They were places where changing seasons meant more than just the Midwest’s heavy, humid air in summer or winter’s snow and bone-chilling cold. They were more spacious and less densely built and populated.

“For many migrants, all of these features would have made those spaces reminiscent of the ‘unbelievably fertile land’ they had left behind in the South. However, whereas those Southern landscapes were irreparably tainted with race discrimination past and present, these Northern landscapes were imbued with the same hopefulness that drove the Great Migration itself.

Hope — and racism

Yet, there is an irony to those dreams and to describing such places as landscapes of hope, as McCammack makes clear. For instance, Black Chicagoans began frequenting Washington Park (named for the nation’s first president) around 1910, and, over the next decade or so, attacks by White gangs “to deny them access to what had been exclusively White spaces” were common.

By 1922, McCammack reports, one White resident suggested — one suspects with some edge of emotion — that the park should be renamed Booker T. Washington Park because more and more African Americans were using it. And, then, as if a switch had been thrown, Whites just stopped going to the park, and Black Chicagoans had it to themselves.

Possession of this “landscape of hope,” in other words, came at the cost of resegregation. And a similar story played out on the city’s beaches.

The 1919 race riot was sparked when a raft on which several Black teen boys, including 17-year-old Eugene Williams, were riding drifted south from the waters off the African American beach at 21st Street and into the waves off the 25th Street beach, claimed by Whites.

Williams died after he was hit on the head by a rock thrown by a White man, becoming one of at least 23 Blacks killed in the riot. Another 15 Whites died, and more than 500 people were injured, about two-thirds of whom were African American.

“A small price to pay”

Ten years later, in an editorial titled “Racial Conflict at the Beaches,” the Chicago Tribune argued for the segregation of the lakefront, echoing generations of politicians and civic leaders in the South. While recognizing the legal right of Black Chicagoans to have access to any public beach, the newspaper noted that, for “a very large section of the white population, the presence of a Negro, however well behaved, among white bathers is an irritation.”

So, the Tribune proposed that African Americans voluntarily agree to avoid the White beach at Jackson Park, “a small price to pay for peace between the races, particularly after proper facilities have been provided for them elsewhere.” As McCammack notes:

“One could scarcely dream up a more striking illustration of the way de facto segregation could operate in the North during the era of ‘separate but equal’ de jure segregation in the Jim Crow South; migrants had escaped the latter only to be confronted by the former.”

This, in a nutshell, is the story of Landscapes of Hope. The natural world — whether in Washington Park or at the African American resort of Idlewild or in a money-making tree-planting job in the Forest Preserves or in rural downstate — was a lifeblood for Black Chicagoans. But their relationship with the natural world was often tainted by White racism.

Landscapes of Hope is an academic book and not for the casual reader. But anyone interested in the history of Black Chicago as well as the history of Chicago and the history of the natural space in which the city was built and has existed for nearly two centuries will find the book filled with important information and telling insights.

Patrick T. Reardon

8.27.21

This review initially appeared in Third Coast Review on 7.27.21.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.