Here is the sad reality at the center of Leo Steinberg’s 2001 book Leonardo’s Incessant Last Supper:

Of Leonardo’s Last Supper we have only an after-image….[O]f the original surface — of its color and atmosphere, its breath of sfumato, its precision of nuance in still life and faces — almost nothing is left.

If these Vincian delights are what you hope for as you enter the former rectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan, you’ll find yourself in heartbreak house.

“An after-image”

The list of great works of art destroyed or lost over the centuries is a long one.

It includes, for instance, the fresco of Odysseus visiting Hades by Polygnatus (created about 450 BC), the ten-story-tall Colossus of Rhodes sculpture by Chares of Lindos (280 BC) and the bronze sculpture of Apoxyomenos by Lysippos of Sikyon (330 BC), as well as many works by such famed artists as Giotto, Titian, Tintoretto, Rubens, Courbet, Van Gogh and Klimt.

For some of the lost art, there are copies, especially for the most admired works. In 1849, a marble version of Lysippos’s Apoxyomenos was excavated in Rome, and, over the past century and a half, at least two bronze reproductions have been discovered. Such replicas give present-day art enthusiasts an insight into why the ancients admired the work so greatly.

With Leonard da Vinci’s Last Supper, we have the art itself — but we don’t.

Within a few years of its completion, the fresco began to rapidly deteriorate from moisture in the plastered wall. Less than a century later, it was already being described as ruined. And then, as Steinberg notes, there were “those well-intentioned or impious hacks who, intermittently for three hundred years, overpainted the self-effacing original.”

The result, even with the most recent cleaning and restoration, is an “after-image” of the original:

- a tantalizing promise of art that, now, is only glimpsed as though through dark, murky glass;

- the frustration of having the work but not being able to see in it all of what Leonardo and his contemporaries saw; and

- the sorrow of encountering a great work of art terminally ill, on life-support.

“Approximate sightings of a vision”

Which means that studying all the many copies of Leonardo’s Last Supper, particularly those created during and immediately after his lifetime, is the best means that art historians and art-lovers have for coming to understand what the master created in its fullness.

For this reason, Steinberg’s book on the fresco is filled with scores of images of the original, of copies and of other related works — a total of more than 150. Steinberg writes:

Some show the mural in photographs taken before the last (or the last but one) restoration, some in its present pallor. Some reproduce early sixteenth-century copies, or details from fastidious engravings.

Since the work lives in no authentic definitive image, the choice in each case was dictated by the issue at hand. Whatever pictures exist are approximate sightings of a vision that has receded forever.

No copy of the Last Supper is a completely accurate record of the original. No copyist was da Vinci’s equal in artistic genius. None could fully understand, much less replicate, the comprehensive, multi-layered vision that Leonardo brought to the creation of this work.

Each, though, speaks about the original — in what the copyist kept in and what he replaced, and what he emphasized and what he played down.

In his book, Steinberg is listening to this cacophony of voices, trying to tease out — from all that is said, shouted and whispered by the copies — what the fresco, when new, had to say. Like a detective, he is searching for clues, avoiding red herrings and discovering wonders.

Copies of copies of copies

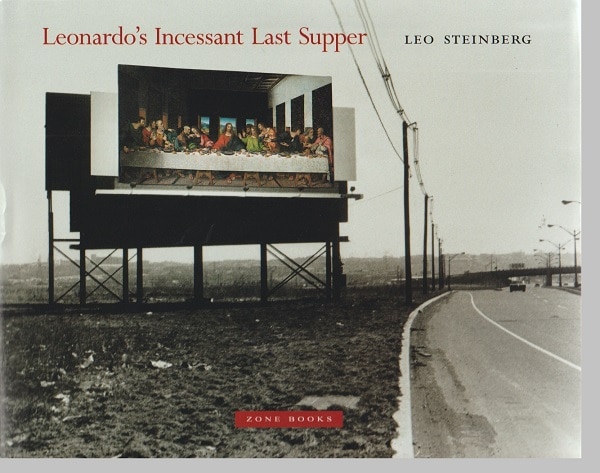

Leonardo’s Incessant Last Supper is Steinberg’s brash, tightly reasoned, deeply felt, idiosyncratic love letter to da Vinci’s masterpiece. The dust jacket itself speaks to the odd and personal nature of this book.

It begins with a black and white photograph, taken in 1967 by Steinberg’s brother-in-law along Route 3 in New Jersey, of a billboard covered by a huge photograph of the Last Supper fresco. This snapshot was included as an illustration with Steinberg’s ground-breaking 114-page essay “Leonardo’s Last Supper” in a 1973 issue of The Art Quarterly.

Leonardo’s Incessant Last Supper is a 287-page expansion and revision of that essay. And, for the jacket, Zone Books has superimposed on the billboard snapshot a color image of one of the best and most accurate copies of the original — the Last Supper at the Abbey of Tongerlo, created by an unknown painter around 1540.

So, follow this:

So, follow this:

- Leonardo creates his Last Supper.

- Four decades later, the Tongerlo copy is painted.

- Several hundred years later, a photograph of the original is taken.

- In 1967, this photograph, hugely enlarged, is affixed to a New Jersey signboard.

- A motorist takes a photograph of the photograph on the signboard.

- The photograph is used with Steinberg’s 1973 essay.

- For Steinberg’s 2001 book, the photograph is used on the cover.

- Also on the cover, in place of the photo of the original Last Supper in the 1967 photograph, a color photograph of the Tongerlo copy is employed.

So, the dust jacket is all about copies of copies of copies, a truly fitting image for a book that is constantly sifting and weighing versions and interpretations of da Vinci’s original creation.

Incessant

And what about the title? Why Incessant? That’s a word that wasn’t used for the heading of Steinberg’s 1973 essay.

I think there are two readings here.

One is that Steinberg is incessant in his efforts to plumb the deepest meanings and art of da Vinci’s great fresco.

He writes about the faces of the apostles and their stances, the way Jesus is seated, the placement of his feet, the way his hands and the hands of everyone else at the table are portrayed and what they signify, the groupings of the apostles (in 3s, 4s, and 6s), the setting in a monastic refectory, the subtle rightward tilt of the figures, the images of crucifixion, the references to the Trinity, and much more.

“Partnered into very coincidence”

And he starts with the moment that the painting captures and the questions that, for five hundred years, have surrounded it.

Some partisans argue that Jesus has just said, “One of you will betray me.” Others, though, contend that this is the instant that Jesus is establishing the Eucharist as the new covenant of his body and blood.

Steinberg asserts that both moments are portrayed, often with the same gestures, in the fresco:

The twin themes under discussion, the narrative and the mystic, do not come rank-ordered, one dominant, the other subdued, unless so graded by interpretation. In the alternative reading proposed in this book, the two — the submission to death and the grant of redemption — come partnered into very coincidence, like the two natures of Christ.

Leonardo’s painting, in other words, depicts two moments, inter-related but separated in time, in a single image. His two-dimensional fresco, envisioning a three-dimensional scene, actually operates in four dimensions simultaneously.

“Moreness”

For Steinberg, the Gospels make it clear that “the Lord’s Supper holds more than one still image can show.” He goes on that “this moreness” is “what Leonardo demands of his art.”

This, I think, is the second reading of the word Incessant in the title — that da Vinci’s genius is unrelenting. The deeper Steinberg goes into the Last Supper, the more he realizes how much more there is to know. Leonardo is a well that can never be fully plumbed.

Steinberg’s contention is that Leonardo put more into his picture than anyone will ever be able to fully experience.

And there are parallel contentions, such as:

- That Leonardo was too great of an artistic genius to put something awkward or wrong in his painting.

- That anything that seems awkward or wrong is just not fully understood.

- That anything that seems ambiguous is ambiguous — is meant to be ambiguous.

- That anything that seems to say two things at once does.

- That the gestures, the faces, the stances, the table, the wine glasses, the bread, the walls and the ceiling, everything in the painting — all communicate on two or more levels, all are rich with two or more meanings.

- That anything that copyists routinely changed is something that bears closer scrutiny since he was the great artist and they weren’t.

- That whenever questions about the fresco seem to require an either/or response, the correct answer is both. Both.

“Congruent godhead and frailty”

Near the end of his discussion of the import of Jesus’s right hand, Steinberg notes that some critics see it as gesturing to indicate that Judas is the betrayer, while others read it as reaching for the wine glass to enact the Eucharist.

Both sides, he writes, are valid, explaining:

The artist is storytelling in two and in three dimensions at once, charging coincidence to define one versatile action. Repeat: as the person of Christ unites man and God, so his right hand summons the agent of his human death even as it offers the means of salvation. This two-natured hand in its congruent godhead and frailty is the profoundest pun in all art.

Like Scripture, there is nothing simple about Leonardo’s Last Supper. Like theology. Like spirituality.

This fresco — as it was created and as it can be envisioned today through the study of its remains and of its copies — is a work of deep faith, even though da Vinci described himself as a free-thinker.

It is something more than art, something sacred.

It is, as Steinberg writes, “the gospel told by this painting.”

Patrick T. Reardon

5.1.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.