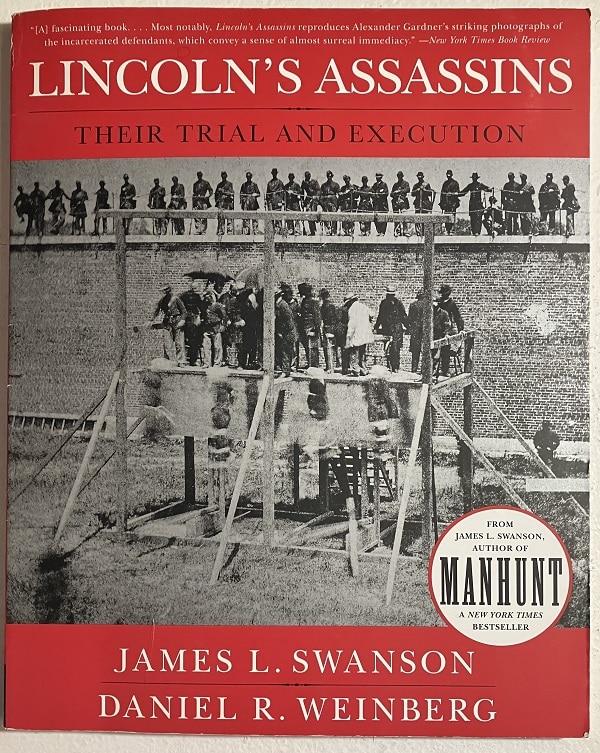

In the preface to their 2001 Lincoln’s Assassins: Their Trial and Execution, James L. Swanson and Daniel R. Weinberg describe their book in several ways.

They write that it is “about what happened after the assassination” — “the frantic hunt for Booth and his accomplices was over, after the mourning and grand funeral pageant for the nation’s beloved president, after both Lincoln and his murderer were dead and buried.”

But, especially, the book is about the trial and sentences of eight accused conspirators. It is, they write, “the first illustrated history of the arrest, trial and execution of Abraham Lincoln’s assassins.”

There are five chapters that deal with the crime itself, the hunt for those responsible, the arrests, the trial and then the execution of four of the accused as well as one chapter about a supposed co-conspirator John H. Surratt, captured , tried and acquitted more than a year later, and one about how Americans looked back on the killing of Abraham Lincoln.

In a 26-page introduction, Swanson tells the story of these events — many of which he later recounted in much greater detail in his 2006 Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer. (A second edition of Lincoln’s Assassins was also published in 2006.)

But the core of the Swanson-Weinberg book is its wealth of illustrations of relics from those days after the killing of the president. As the authors write:

This book is a scrapbook of another time, preserving the words once read and the images once seen by people long gone…a book that captures the mood of the people and the visual iconography of the spring and summer of 1865 and one that evokes the spirit of the age, when the death of one man after the deaths of so many caused a nation to weep.

Scrapbook

As with any scrapbook, there’s a hodge-podge nature to the collection of items — newspaper stories, pieces of rope, photographs, badges, letters, magazine illustrations and so on.

As with a museum, there is no way for such a collection to be complete or absolutely representational. Too much time has passed. Items made of paper and other ephemera are too fragile for more than a tiny number to have survived. Important relics were long ago thrown in the trash.

Still, the myriad illustrations here are evocative. And I imagine that, as with any scrapbook, a reader will be struck by those items that resonate personally.

“Animal manhood”

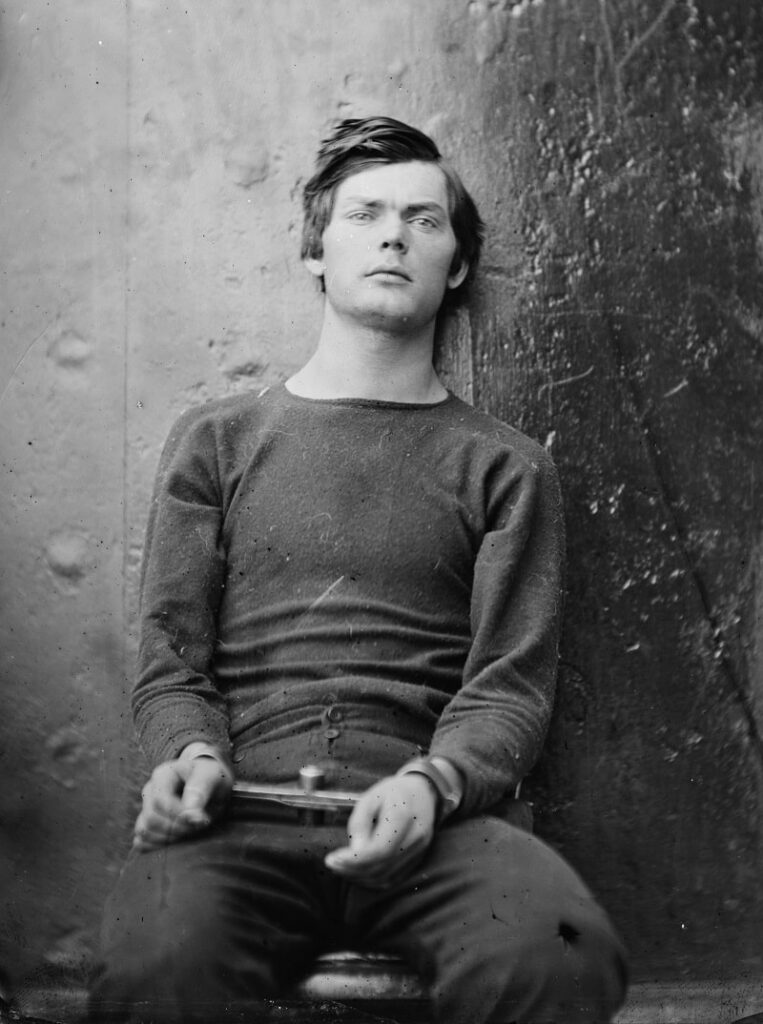

For me, it’s the photographs of the conspirators, especially the one of a shackled Lewis Powell, called Lewis Payne, who came close to killing Secretary of State William Seward on the night Lincoln was killed by John Wilkes Booth.

He is simply beautiful in this photograph by Alexander Gardner. He could be a model from the pages of a fashion magazine.

This isn’t just my reaction. Swanson and Weinberg note that much of the coverage of the conspirators dealt with the strength, manliness and “magnificent physique” of Powell. They quote Perley Poore, the contemporary writer who published the transcript of the trial:

“Lewis Payne was the observed of all the observers, as he sat motionless and imperturbed, defiantly returning each gaze at his remarkable face and person. He was very tall, with an athletic, gladiatorial frame; the tight knit shirt which was his upper garment disclosing the massive robustness of animal manhood.”

Herold and Atzerodt

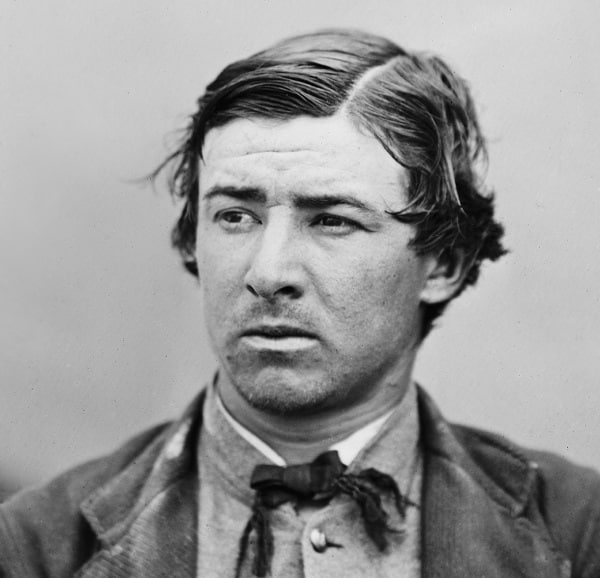

Another of the conspirators, David E. Herold, who helped Booth escape Washington, comes across in his photograph as very modern-looking. (He reminds me of a young Tom Hayden, the 1960s anti-war activist.) Perhaps that’s because he’s clean-shaven. The image is very humane in its way.

I look at the photograph of George A. Atzerodt, and all I can think of are folk and country singers of the 1970s. John Denver comes to mind although I think that’s not fair.

These are three of the four defendants who were convicted by the military tribunal for the conspiracy against Lincoln and the U.S. Government and hanged on July 7, 1865.

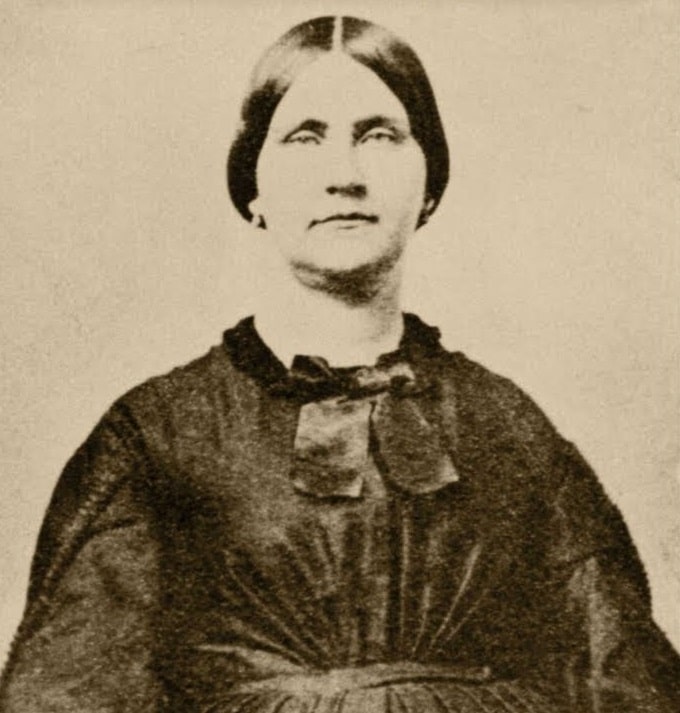

“Her, too?”

The fourth was Mary Surratt, the owner of the Confederate-loving boarding house in Washington where the conspirators met and the first women executed by the federal government. For unknown reasons, Gardner did not photograph her before the trial, but Swanson and Weinberg provide one from another source.

Leading up to the moment of execution, there was great hope that Surratt would be spared death by President Andrew Johnson, but no reprieve was given. In perhaps the most poignant lines of his introduction, Swanson writes:

The order to proceed startled the hangman, Christian Rath, who asked, “Her, too?” before he placed the noose around her neck. “She cannot be saved,” replied [General Winfield Scott] Hancock.

One of the oddest of the images in Swanson and Weinberg’s scrapbook is the photograph of a custom-made, cushioned case holding not something jeweled or precious but a common brick. On a card, under the lid, are these words:

Mary E. Surratt

A brick from the wall of her cell in Old Capital Prison.

Washington, D.C.

Lincoln was mourned. So, in some parts of the nation, were the conspirators.

Patrick T. Reardon

4.4.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.