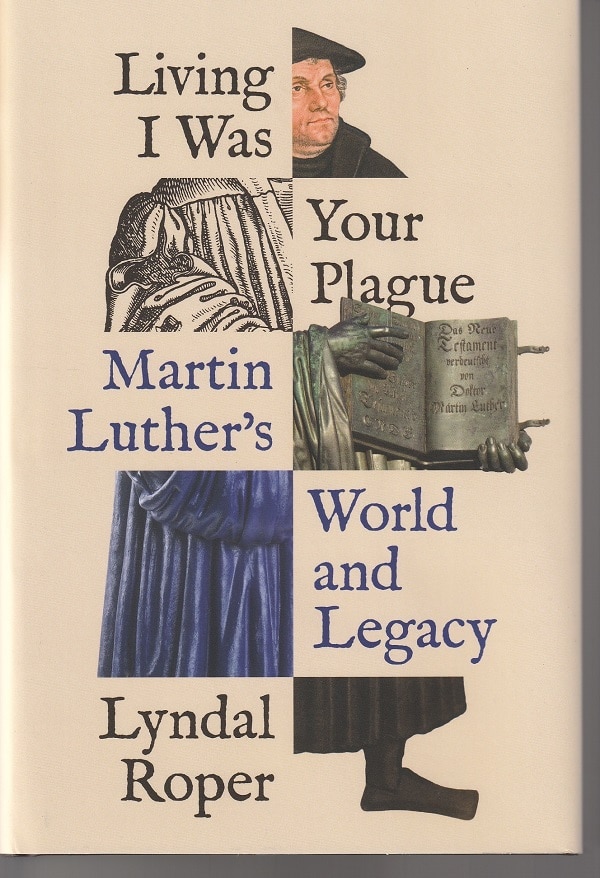

Martin Luther, the world-changing religious reformer who sparked the Reformation, was also “a great hater, unrelenting in his hatred of the papacy,” writes historian Lyndal Roper in her book Living I Was Your Plague: Martin Luther’s World and Legacy, from Princeton University Press.

He was also a man who put “his capacity for aggressive hate…at the service of his anti-Semitism.”

Luther liked to call the head of the Catholic church the “ass-fart pope,” and, in a tract written shortly before his death, he asserted that papal decrees were “sealed with the devil’s own dirt” — i.e., the devil’s excrement — “and written with the ass-pope’s farts.” The former monk reveled in his anti-papal assaults, bragging,

“Living I was your plague; dead I will be your death, O Pope.”

His slanders against Jews were filled with much more bitterness and evil invective, such as his assertion that they drank “Judas piss” from the hanged body of the disciple who betrayed Jesus. And there was much worse.

Such language, Roper notes, “can shock modern viewers, attuned to hate speech and its consequences.” Hate speech is dangerous, demeaning — the language of a bully. But of a theologian and hymnwriter?

Yet, Luther’s hate speech was a key thread in his personality, in the promulgation of his theology and in the definition of his new church — and it has been a dark legacy for Lutherans ever since his death.

“Difficult hero”

In her introduction to Living I Was Your Plague, Roper writes that Luther is a

difficult hero, with his stodgy determination, his love of beer and pork, his relentless hatreds, his penchant for misogynist quips, and his four-square masculine stance [and one who] has always been a divisive figure.

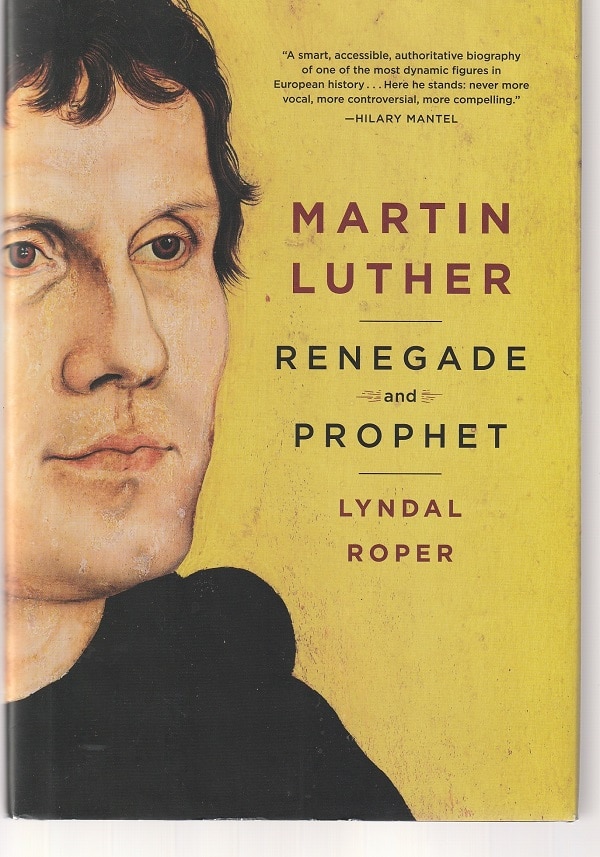

She should know. She spent ten years researching her 2016 biography Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet, a book highly praised by the New York Times, the Guardian and the Washington Post.

It was one of hundreds of Luther-related books published in celebration of the 500th anniversary of Luther’s publication of his 95 Theses, a set of theological propositions that were the opening salvo of the Reformation. (Whether Luther actually hammered the paper onto the door of All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg on 31 October 1517, as legend has it, is questioned by many historians.)

Living I Was Your Plague, published last year, is built around issues that arose and influenced the worldwide anniversary festivities. Its seven chapters began as lectures given at Queen’s University, Belfast, and at Princeton University. Roper writes in a preface:

I hope that my view of Luther’s masculinity and his knotty character may open up the discussion further about how we commemorate great men without losing sight of their frailties and violence.

“Not done enough”

As the 500th anniversary approached, there had been expectations that Luther, the translator of the Bible and inventor of the German language, could be employed as a defining focus of national history — as an edifying and uplifting figure in contrast to the darkness of Nazism and the holocaust.

Those hopes were blown out of the water, however, in 2014 when Thomas Kaufmann, one of the world’s leading authorities on the Reformation, published Luther’s Jews: A Journey into Anti-Semitism (available in English in 2017). It was a book, writes Roper, “that acknowledged Luther’s anti-Semitism once and for all, and which did not excuse it as a product of his times.” Suddenly, anti-Semitism was part of the German national debate for the first time since World War II.

For Roper, the controversy left her uncomfortable. In her biography of the reformer, she had devoted seven pages to Luther’s hatred of Jews, and she writes:

I realized that I had not done enough to interrogate Luther’s anti-Semitism or to ask how far it extended into Lutheran theology. And I sensed that I needed to confront the less comfortable sides of his legacy.

“Merciless in his humor”

The subjects she deals with in Living I Was Your Plague include the immensely influential friendship and collaboration of the former monk with the artist Lucas Cranach the Elder which resulted in the widespread reproduction of Luther’s likeness, making him perhaps the most recognizable face in early 16th century Europe and boosting his identification as the leader of the Reformation.

Also covered in Roper’s chapters are what Luther and other leaders thought about dreams, what Luther kitsch was available during the 500th anniversary, and how Luther was quick to engage in the written equivalent of fisticuffs with opponents. Indeed, as another chapter relates, the former monk was a great name-caller:

He devised animal names for his opponents: there was Murner the cat, Augustin von Alfeld the donkey, Emser the goat…He was also merciless in his humor about his antagonist Johannes Cochlaeus, whose name could be mocked as meaning the spoon, the snail, or — even better — the vulva.

Luther even nicknamed one ruler Wider Hans Wurst, or Sausage Man. He had much more and worse for the Pope whom he asserted was the Antichrist.

“How raw Luther’s anti-Semitism could be”

Roper’s key chapter, however, is “Luther the Anti-Semite,” a 34-page treatment that is nearly five times longer than the section in her biography of the religious figure.

It’s rough reading. And, apparently, it was rough writing. Roper includes enough examples to make her point but indicates that there are many more.

For the sake of this review, I’ll just mention one example. After Roper notes that it is easy “to forget how raw Luther’s anti-Semitism could be,” she offers as an illustration his assertion that Jews worshiped excrement:

The devil has…emptied his stomach again and again, that is a true relic, which the Jews, and those who want to be a Jew, kiss, eat, drink and worship…He stuffs and squirts them so full, that it overflows and swims out of every place, pure Devil’s filth, yes, it tastes so good to their hearts, and they guzzle it low sows.

Luther’s anti-Semitic writings, Roper notes, “are more extreme and have none of the humor that leavens his assault on the papacy, or his diatribes against individuals.”

Indeed, Luther’s anti-Jewishness wasn’t an expression of the common anti-Semitism of his time and place, a bias that asserted that Jews saw Christians as disgusting and unclean. It was something much more his own.

Fantasies this disturbing and deep belong to the kind of material I encountered when working on the witch craze [Her 2004 book Witch Craze: Terror and Fantasy in Baroque Germany]. They suggest that Luther’s anti-Semitism was linked to deep phobias buried in the unconscious, and go back to early infancy, connected to ideas about eating, the boundaries of the body, excrement, and to fears of dissolution.

“His right, not theirs”

Yet, psychological disturbances weren’t the only explanation for Luther’s antipathy toward Jews.

They had what Luther wanted for himself and his church, and Luther’s foul diatribes against them were part of an effort to lay claim to the legacy of Judaism.

First, Luther wanted those who followed him — those who became the Lutheran church — to be seen as God’s Chosen People. He and those who followed him saw God’s light and lived it, unlike the Catholics and unlike the Jews. “He wants to arrogate their history for himself and his own church,” writes Roper.

Second, Luther wanted to be acknowledged as a better Hebraist and Bible commentator than the rabbis. Indeed, he, in effect, wanted to be the one, central, only rabbi of the new church. As Roper notes:

Like a rabbi, his standing derives from his position as interpreter of the Bible, and so he reserves his full scorn of the Jews as “piss eaters” for their (in)ability to interpret scripture; this is his right, not theirs.

There is a sense in which he wants to take for himself everything that is the Jews’, to ingest it, and make it his own…

“Extreme irrationality”

What is most puzzling about Luther’s anti-Semitism, writes Roper, is that “it is animated by a deep recognition and identification.” Luther identifies with the Jews as God’s Chosen People and with the rabbis as the interpreters of the Bible — but he wants, needs, to claim those positions solely for himself and his new church.

All of this has had ramifications for Lutheranism down through the centuries and still does today. And Roper concludes this chapter:

Any serious consideration of Luther’s anti-Semitism must confront its extreme irrationality, its use of bodily imagery and its mobilization of revulsion. It has to recognize that Luther’s anti-Semitism went further than that of many of his contemporaries, and was not merely the expression of the age.

Roper’s chapter and Kaufmann’s book are part of a new effort among Lutherans and scholars of religion and the history of religion to get a better understanding of this poisonous aspect of Luther’s story and of the heritage that he bestowed on his followers.

His insights into the Bible and spirituality brought bright light and fresh richness to his age and those that have followed — but his toxic intolerance has tainted religion and helped fuel pain, violence and injustice for more than five hundred years.

Patrick T. Reardon

5.17.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.