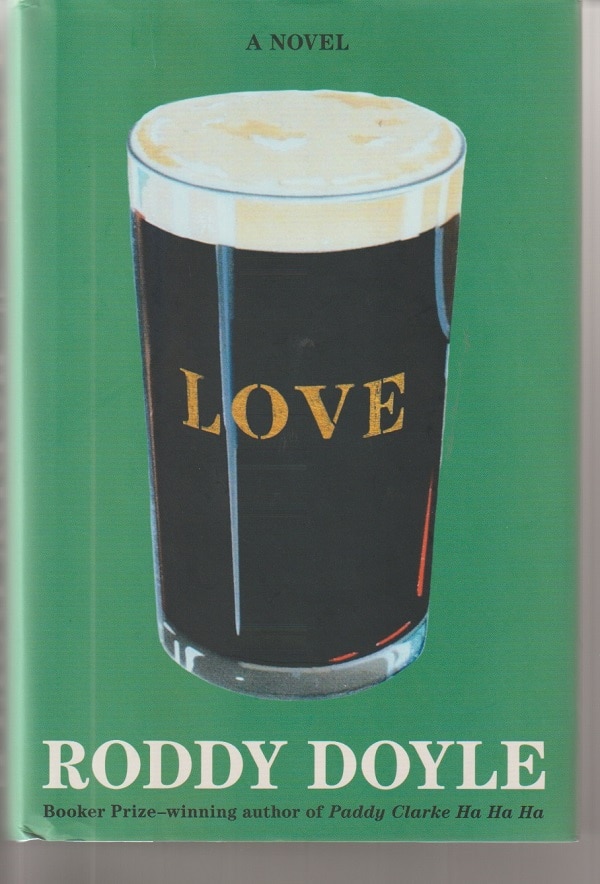

There’s much that’s audacious about Roddy Doyle’s new novel Love.

There’s the title, first of all. It seems fitting for some sort of Romeo and Juliet story, with or without the tragedy, a tale filled with yearning ache, hot romance and easy sentiment.

Instead, Doyle’s book is tightly focused on two aging Irish guys, Davy and Joe, who, over the course of a night, drink and gab in a series of Dublin pubs. They’re not exactly eye candy.

And it’s not as if these guys, both about 60, are engaging in witty repartee. Each is carrying a heavy burden of angst. Each has a chip on his shoulder and hollows in his heart, and, as the drinking goes on, each weaves in and out of coherence, easily angered, easily distracted onto tangents.

The result is a claustrophobic reading experience, and that’s the riskiest aspect of Doyle’s endeavor.

It’s as if the reader has been shanghaied to accompany these two formerly close friends who don’t know each other well anymore and to listen to their fractured story-telling and jockeying for attention — but without the ability to interrupt or do anything to make things more intelligible.

It could be a recipe for disaster, but, despite all the risks, Doyle pulls it off. Love is poignant and heartfelt and jarringly human, a work of great skill and power.

Perplexing nature of existence

The chaotic and confusing conversation of Davy and Joe, as Doyle presents it, reflects the tumult of bewildering emotions and experiences that the two men are attempting, on the edge of old age, to comprehend. It’s also a metaphor for the perplexing nature of human existence, particularly when it comes to love.

Yes, despite being riveted to these two flawed men in their hours of drinking, declaiming and debating, this novel is about love — love with its full panoply of delight, irritation, boredom, pain, deception, vulnerability, fear and joy, love with its full measure of tenderness and guilt, care and carelessness.

It’s about Davy’s love for his father and for his wife Faye and their children, and about Joe’s love for his mother and for his wife Terri and their children and for a woman from the past who greets him with a kiss outside a high school classroom.

And, as much as they get on each other’s nerves, as much as they don’t seem to recognize or even like each other — at several points, Davy is on the verge of abruptly leaving — this is a novel about the love that Davy and Joe share.

“Knew it was her”

The novel is told from Davy’s point of view.

Nearly four decades earlier, when both were in their early 20s, he and Joe had hung together through a routine of bar-hopping that gave them a framework for growing from boys to men. Later, Davy moved to England for work, coming back about once a year to visit his widower father and, for one night, to see again Joe.

The novel opens:

He knew it was her, he told me. He told me this a year after he saw her. Exactly a year, he said.

—Exactly a year?

—That’s what I said, Davy. A year ago — yesterday.

The “her” is an attractive cello-playing woman whom they saw, back around 1981, in a crowd of musicians in the pub called George’s.

Both yearned for her — “We adored the same woman,” Davy explains — and they wheedled their way into the outer edges of her circle of friends, last seeing her at the party for her engagement with someone named Gavin.

Her name is Jessica although Davy is pretty sure that he and Joe didn’t know it back when they were young and lusting for her. Joe isn’t sure either. When she came up to him in the school corridor, kissed him and told him it was great to see him again, he couldn’t remember her name. She later said it to him in a phone call.

Illusion and delusion

A subtext in Love is the sponginess of memory, the inability of the human mind to hold onto facts and images without reshaping them into something more understandable, more memorable. What is illusion? What is delusion?

Joe has come to think that he may be the father of Jessica’s oldest child, a son living in Perth, Australia. Did he and Jessica have sex way back when? Davy doesn’t think so. Joe seems unsure.

As the opening sentences of the novel indicate, the whole of Love deals with Joe’s attempt to explain to Davy how he met Jessica and why he left Terri to be with her and what living with her is like.

One thing that’s clear is that Joe and Jessica don’t have sex, but everything else is confusing and hard to explain. Joe likes being with her because she’s had a hard life and his presence makes her happy. But why such warmth to Joe from a woman who was little more than a cipher nearly 40 years earlier? Why does she act as if Joe has been with her throughout her life? And why no sex?

These and many other questions are raised often by Davy, frequently in a harsh, prosecutorial way. At first, it seems that Davy is just that way, a bit of a jerk, but, as the novel moves on, the reader is also asking such questions and being exasperated by the lack of straight answers.

Two Everymen

Joe’s tale of his encounter with Jessica, as disjointed and muddled as it is, dominates the hours of conversation. Joe asks Davy few questions about his own life, and Davy doesn’t seem eager to bring anything up.

But, through flashbacks, Davy does tell the reader what has happened to him over the last four decades, including his courtship and marriage with Faye and a deeply disturbing health scare he’s had. That doesn’t get into the conversation, but Joe, on one of his tangents, takes time to describe his own fractured skull, from hitting his head in the attic.

Davy and Joe are two Everymen. Yes, they are near-elderly guys who are facing questions of affection, communication, memory and morality that fit with their particular time in life.

But these are questions that each of us faces, no matter what our age or situation, all the time and throughout our life.

Always improvising

Love is akin to skat singing in jazz.

When we talk about important things, we’re always improvising. And the words we use don’t really make sense, don’t really capture what we are feeling and thinking. They’re like a human voice trying to mimic a trumpet, to say what can’t be said.

What does it mean when Ella Fitzgerald skat sings in “How High the Moon”? The sounds have a meaning that transcends the line of logic. That’s what’s going on as Joe talks and Davy asks his questions.

Joe has taken an action in moving in with Jessica. He has many ways of trying to explain it, and no ways. It’s the action that speaks loudest.

And, when Love comes to its end, it’s action that speaks loudest. Like the action of a taxi driver who does the two men a good deed.

On the final page, while waiting for another cab, Joe and Davy remember that earlier driver:

—He was sound, I said.

—He was, said Joe. —Sound.

We watched the taxi slow, and stop.

—You’ll soon be home, Davy, said Joe.

—Yeah, I said. —I will.

Maybe that’s the best we can hope for — that, in the tornado of life, in the chaos of existence, we can, as often as possible, be sound. That we can be seen by others as sound.

.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.22.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.