Historian Lyndal Roper published her biography Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet in 2016, but, even as it was going to press, she knew that there was more she had to address in the Protestant reformer’s life.

That was because of a book that had been written by Thomas Kaufmann, an expert in the Reformation and ecclesiastical history and the man many consider “the leading interpreter of Luther in our time.”

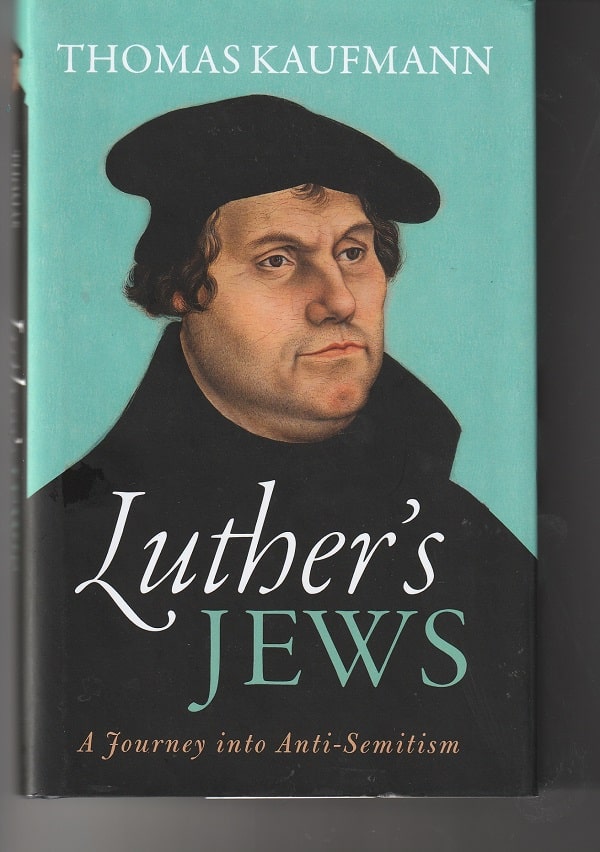

What happened is that, in 2014, as preparations were reaching their climax to make Luther the face of the 500th anniversary of the Reformation in Germany, Kaufmann published in German Luther’s Jews: A Journey into Anti-Semitism. Three years later, during the anniversary year, the English translation was issued by Oxford University Press.

For centuries, Lutheran theologians and church figures had explained away Luther’s hatred of Jews as being common in his era or somehow the result of one or another form of theological reasoning — in any case, just a “regrettable lapse,” Roper writes, “unfortunate but incidental.” Even more of this took place following World War II when “Lutherans were at pains to insist that there was no direct line leading from Luther’s views to the Holocaust.”

Then, Kaufmann did what no one else had been willing to do.

As Roper notes, his book “acknowledged Luther’s anti-Semitism once and for all, and…did not excuse it as a product of his times.” It was, for the first time in half a century, “a genuine confrontation with Luther’s anti-Semitism.”

And the book was a key reason for the writing of Roper’s own 2021 book Living I Was Your Plague: Martin Luther’s World and Legacy in which she devotes a 34-page chapter to “Luther the Anti-Semite.”

Forerunner?

Luther’s Jews is a sober, painstaking, carefully written book, rooted in Kaufmann’s deep knowledge and familiarity with Luther’s writings and with five centuries of Lutheran readings of the reformer and the religion he founded.

In many ways, he does not go as far as Roper’s Living I Was Your Plague which examines in detail Luther’s animalistic and excremental slanders against Jews and likens his often psychologically disturbed ramblings to modern-day hate speech. Yet, he was the pathfinder who blazed the trail that Roper later followed.

Kaufmann notes in his opening pages that the German volkisch ethno-nativist movement and the Nazi Party sought to identify Luther as a precursor of their efforts to rid the nation of Jews — “as a forerunner of anti-Semitism.”

Indeed, their accusations that “the ‘Jewified’ Protestant church [was] suppressing this essential characteristic of his” led some Lutheran theologians to stress the reformer’s late diatribe On the Jews and their Lies “as a way to connect with the anti-Semitic Zeitgeist.”

“Certainly a factor”

Kaufmann reports that Adolf Hitler, a nominal Catholic, “allegedly hailed Luther as a ‘great man,’ a ‘giant,’ who ‘at a stroke’ had pierced the ‘twilight’ and seen ‘the Jews as we are only beginning to see him today.’ ”

The Fuhrer, though, didn’t learn his anti-Semitism from the Protestant reformer. In fact, it appears he knew nothing of Luther’s writing except what he read from Nazi propagandists. So, Kaufmann can write at the end of his book:

We are probably in a position to exclude the possibility that Luther’s own texts became a direct “inspiration” for the Third Reich’s policy of exterminating the Jews.

There’s more, though, and it comes in Kaufmann’s brutally honest next sentence:

But [Luther’s texts] were certainly a factor in making the Holocaust possible, for they helped create an attitude of mind that paralyzed any kind of civil courage on the part of the Lutheran population.

Kindness with a catch

The irony is that, at the start of his reforming career, Luther wrote an essay that said Jews should be treated with kindness. At least, that’s what his words seemed to say in That Jesus was born a Jew, published in 1523.

But it wasn’t so simple.

Indeed, Kaufmann discusses this in his chapter titled “The Jews’ Friend?” which has a subtitle “Luther’s ‘Reformation’ of Attitudes towards the Jews.” The question mark is important.

Some Reformation clergymen took him at his word and, acting “upon the encouragement by Luther to engage in a ‘kind’ manner toward the Jews,” set aside their societal biases and were open to Jews as fellow humans.

The goal, though, wasn’t toleration for toleration’s sake. It was to kindly convince Jews of the rightness of the Christian message, leading them to be baptized. That’s what Luther wanted when he talked about kindness.

The kindness was conditional, and, as Kaufmann notes, Luther didn’t really think it would work. “Luther distrusted Jews who were willing to be baptized.” He called them “rogues,” i.e., devils.

For centuries, Lutheran theologians have described the reformer’s attitudes toward Jews as being prompted by Jewish beliefs. Kaufmann writes:

[Luther’s] Early Modern version of anti-Semitism…was undoubtedly rooted in a religiously motivated anti-Judaism, but insofar as it attributed particular negative characteristics such as deviousness, the lust to kill, and love of money to Jews as Jews it went beyond anti-Judaism.

“Contrary to doctrine and faith”

As Luther neared the end of his life and was afflicted by losses among his children and friends, Luther publicly turned his back on the “kindness” approach.

In the two decades since his “kindness” essay, few Jews had converted. They’d had their chance, and so he gave up on toleration and lashed out in On the Jews and their Lies, published in 1543. Kaufmann writes:

First Luther treated the “lies” told by Jews “contrary to doctrine and faith,” beginning with their arrogant “boasting” on account of their blood, their “preening” because of the Law and their other “marks of distinction” such as the promise relating to the Temple and their land.

Of course, the “doctrine and faith” to which Jews were contrary was Luther’s doctrine and faith, not their own. Similarly, their “boasting” was very quiet compared with Luther’s own flood of self-assured interpretations of the Bible and the requirements of God.

“We are at fault for not killing them”

In the second half, he trotted out a whole raft of bitter slanders against the Jews, many of which he had rejected in his early essay.

He claimed that Jews were guilty of poisoning wells and of abducting children and running them through with spikes. He asserted that a rabbi had referred to Mary, the mother of Jesus, as Haria, a dung heap. Then, in full, unrestrained fury, Luther wrote:

We are to blame for not avenging the immense amount of innocent blood they shed…We are at fault for not killing them, but rather, as a reward for all their murders, curses, blasphemies, lies and defilements, we allow them to remain freely in our midst…

And he came up with what he called his “final solution to the Jewish question.”

He called upon Christian rulers to restrict the activities that were permitted for Jews as well as where they could live, and for Christians to burn synagogues to the ground. It should be noted, however, that Luther had not included in this “final solution” any talk of extermination.

“Exorbitant ferocity”

In his conclusion, Kaufmann writes that, yes, Luther was a man of his time. But not only that. He writes:

Luther’s attitude to the Jews, though it makes him incomprehensible, indeed unbearable, to people of our time, is very much of his time.

But there was a difference. For one thing, he wasn’t just any man of his time, but the man who overturned the power of the Catholic church and kicked off the Reformation and founded the Lutheran faith. His words carried great power.

And, from his seat of power, Luther spoke with great brutality:

What distinguished Luther’s position from that of his contemporaries, however, was the exorbitant ferocity of his polemic and the dramatic change that occurred in his standpoint of how the Jews should be treated.

Kaufmann writes that “Luther’s hostility to the Jews was not simply the ‘shadow side’ of his ‘inner self,’ his personality, or his theology, which we can underplay or obscure without making any fundamental difference to how he might be viewed as a whole, for a shadow cannot be separated from the body that casts it.” Indeed, he concludes that “Luther’s anti-Semitism as an integral component of his personality and theology.”

Kaufmann makes these assertions in his book’s conclusion which is subtitled “A Fallible Human Being.”

Yes, Luther was a fallible human being, but the power of his anti-Semitic poison has seeped through the last five centuries of humankind. It helped make the Holocaust possible. And much other evil.

Patrick T. Reardon

9.7.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.