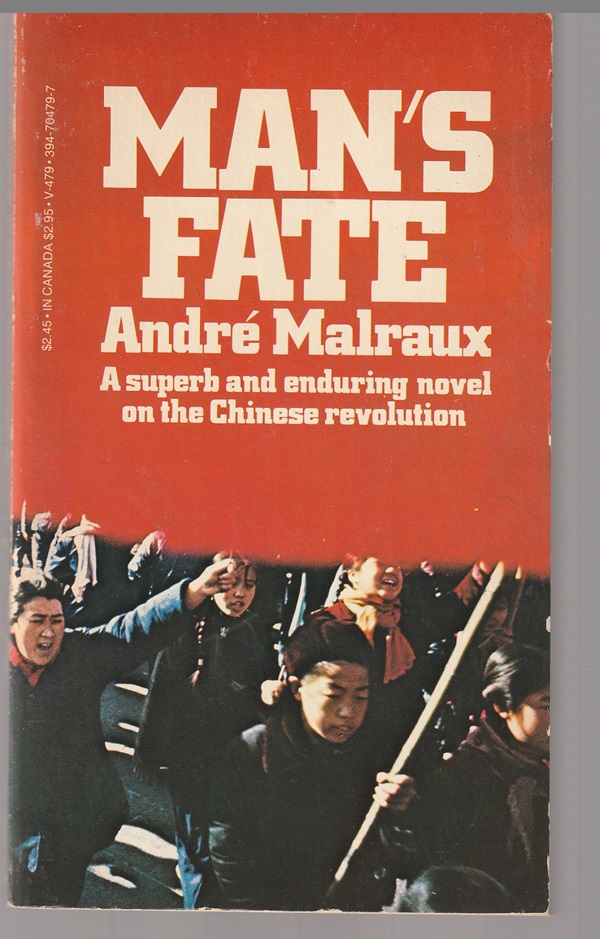

In his novel Man’s Fate, Andre Malraux tells the story of the Communist insurrectionists who took control of Shanghai in March, 1927, and then were massacred a month later by the forces of their erstwhile ally General Chiang Kai-shek.

One of the plotlines in the book — published as The Human Condition in French in 1933 and in English the next year — involves an attempt to assassinate Chaing, and it brings to mind a novel published four decades later in 1971 by the English writer Frederick Forsyth, The Day of the Jackal.

In Forsyth’s story, the OAS, an actual French paramilitary terrorist group, hires a professional hit man to kill President Charles de Gaulle. The book is set in the early 1960s, and readers knew when they picked it up that no attempt to kill de Gaulle had been successful. (He died of natural causes in late 1970.)

The readers of Malraux’s book similarly knew that Chaing had not been assassinated. In fact, he was to remain in power until the mid-1970s.

The two books are very different. Yet, each is considered a classic.

More than half a century after it was published, The Day of the Jackal routinely appears high on lists of great political thrillers. For instance, it ranks third among more than 400 such books at goodreads.com and is listed second among the 18 “essential political thrillers” by abebooks.com.

Far from entertainment

Man’s Fate has to do with politics, and, like a thriller, it grows in suspense and tension. But it is far from the work of entertainment that Forsyth’s book is.

In 1999, the Paris newspaper Le Monde surveyed thousands of readers and published a list of the 100 most memorable books of the 20th century, regardless of language.

Man’s Fate was listed fifth. And other books high up on the list give a sense of why Malraux’s book was so popular.

The Stranger by Albert Camus (1st), The Trial by Franz Kafka (3rd), Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett (12th) and Being and Nothingness by Jean-Paul Sartre (13th) are all books of existential pain and despair, and Man’s Fate fits right in with them.

“Intensely human”

Consider, for instance, this scene early in the novel: Katov, a Russian and one of the organizers of the insurrection, is riding in a launch with other armed men to rob a shipment of guns from a boat, and, as usual, before entering battle, he is remembering when he was captured with his battalion by the White Guards during the Russian Civil War.

On the snow-covered ground in the “greenish dawn,” those soldiers who identified themselves as Communists — Katov among them — were ordered to take off their coats and dig a pit.

They dug in the face of machine guns and White Guards armed with a revolver in each hand. They knew they were digging their grave. It took a long time because the ground was frozen.

The silence was limitless, vast as the snow that stretched out as far as the eye could reach. Only the clods of earth fell with a brittle sound, more and more hurried. In spite of death, the men were hurrying to get warm. Several had begun to sneeze.

‘That’s good now. Halt!” They turned around. Behind them, beyond their comrades, women, children and old men from the village were herded, scarcely clad, wrapped in blankets, mobilized to witness the example. Many were turning their heads, as though they were trying not to look, but they were fascinated by horror.

“Take off your trousers!” For uniforms were scarce. Many hesitated, because of the women. “Take off your trousers!” The wounds appeared, one by one, bandaged with rags: the machine-guns had fired low and almost all were wounded in the legs. Many folded their trousers, although they had thrown their cloaks.

They formed a little line again, on the edge of the pit this time, facing the machine-guns, pale on the snow: flesh and shirts. Bitten by the cold, they were now sneezing uncontrollably, one after the other, and their sneezes were so intensely human, in that dawn of execution, that the machine-gunners, instead of firing, waited — waited for life to become less indiscreet. At last they decided to fire.

The Reds recaptured the village the next night, and 17 of the victims, including Katov, were still alive and were saved.

Blaring indiscreetness

This incident encapsulates the book Man’s Fate and all the action that takes place in the 22 days covered by the novel. It also encapsulates Malraux’s view of man’s fate, i.e., the human condition.

Sneezing, they were sneezing. What could be more human than sneezing? Wounded and cold, standing without pants, embarrassed before the eyes of the women, the Red soldiers, digging their own grave, were as human as a newborn baby, as the frail grandmother in the front pew of the church, as the bride and her groom on their wedding day.

They were digging the hole in which they would die, but, because the exertion of digging warmed them, they worked fast — though it hastened death.

The White Guards facing them with their handguns and machine-guns — they were human, too, wanting the pants of the men who were to die. They were cold, too, and were willing to wear the pants of a dead man in order to be warm.

And, as the line of Red soldiers stood their along the pit, trouser-less and sneezing, sneezing, sneezing, the White Guards held their fire.

They were the long arm of ideology and bureaucracy and politics and power, but they could not fire in the face of such blaring indiscreetness of humanity.

And then they could.

Humans in an inhuman world

Where is the meaning here? For Malraux, there is none.

No meaning for why one set of soldiers is before the machine-guns and one set behind the machine-guns. No meaning for the living and the digging and the sneezing. No meaning for the dying.

No meaning for the not shooting. And then for the shooting.

No human is pure and innocent. No action has any tinge of joy or faith or sense. Or meaning.

Man’s Fate is filled with flawed people who are caught up in and are being crushed by an inhuman system, an inhuman machine that grinds anyone and everyone down to dust, an inhuman world.

“If only they are dead!”

The wisest man, Old Gisors, is a drug addict. His son Kyo can see what is about to happen to the insurrectionists but can’t halt it and makes no attempt to avoid it. Kyo’s wife May sleeps with a business colleague because he was so urgent in his demands, wounding her husband in a way she hadn’t expected.

After the start of the massacre, Hemmelrich, a German phonograph dealer caught up in the insurrection, returns to his shop for his wife and sick child. He finds it in shambles, “cleaned” with grenades.

The woman was slumped against the counter, almost crouching, her whole chest the color of a wound. In a corner, a child’s arm; the hand, thus isolated, appeared even smaller.

“If only they are dead!” thought Hemmelrich. He was especially afraid of having to stand by and watch a slow death, powerless, only able to suffer, as usual…Through the shoe-soles he could feel the stickiness of the floor. “Their blood.” He remained motionless, no longer daring to stir, looking, looking…He discovered at last the body of the child, near the door which hid it.

“A child’s arm”

Like the Katov scene early in the novel, this moment near its end is an encapsulation of the book and of its author’s philosophy.

What could be more human and pitiable than the sight of “a child’s arm” in a corner? What could be more inhumane than circumstances that bring Hemmelrich to the point that he hopes his wife and child are dead?

What can the meaning be of the deaths of this woman and her child, uninvolved in any way in the insurrection? Of the deaths of such harmless and un-guilty humans?

And Hemmelrich is left “powerless, only able to suffer, as usual.”

Patrick T. Reardon

10.17.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.