There is much that can be, and has been, said about Martin Luther, the man who triggered the Reformation and the break-up of western Christianity into myriad sects.

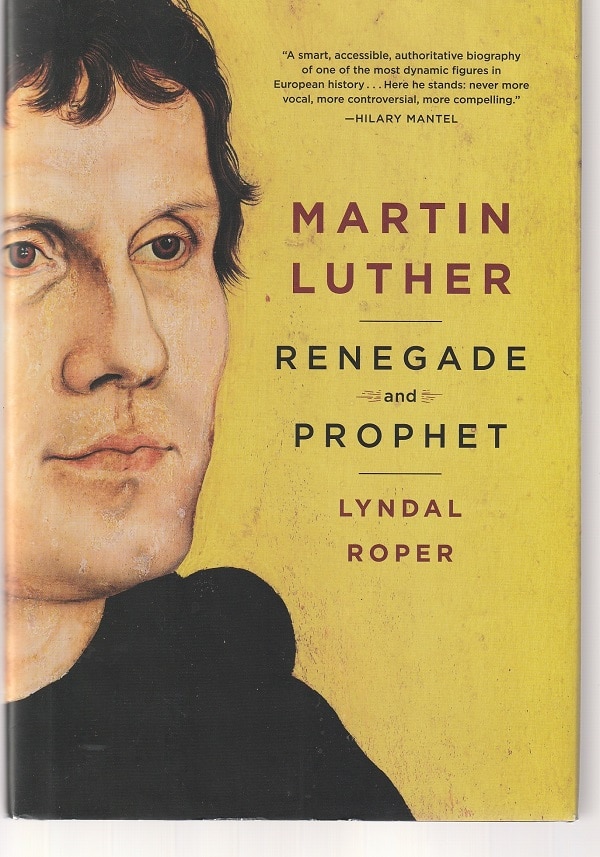

Consider that, in the last dozen pages of her engaging and perceptive biography of the monk who challenged the Pope, Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet, historian Lyndal Roper notes, almost in passing, that Luther was a brilliant hymn writer.

[H]is introduction of sung hymns into the liturgy, with its engagement of the whole congregation — men, women, and children — transformed the place of music in religion.

Yet, it’s more complicated than that, as Roper explains. Luther’s works and the other Lutheran hymns that followed were intrinsic to the music of J.S. Bach, creator of some of the most transcendent music ever written. There was a dark side to this, she notes, in the highly emotional way Bach dramatized the death of Christ:

In the St. Matthew Passion the angular melodic line spares the listener nothing of the viciousness of the Jews’ shouts of “Lass ihn kreuzigen” (“Let him be crucified”), and follows this with heartfelt individual meditations on Christ’s suffering; the implicit anti-Semitism of the glorious music can be hard to take.

“Accommodation”

Luther, for good and ill, shaped the German culture in innumerable ways — the language, the music, the way of thinking. And his influence has continued for more than five hundred years.

Another example: Early on, Luther developed a political theory rooted in the Jesus statement, “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” For him, this meant that Christians are required to obey civil authorities and are forbidden to rebel, even when a ruler acts unjustly.

In other words, in the years when Luther was rebelling vociferously against the Pope in Rome, he was a conservative, even a reactionary, when it came to those in secular power. Thus, when many Germans took his religious rebellion into the realm of social justice in the Peasants’ War, he railed against the protestors.

This strategy meant that those princes and other in power were able to give protection to Luther and his followers without fear of it blowing up in their face politically. However, the policy was one that became woven into the fabric of the Lutheran church and German society, with dire ramifications. Roper writes:

His position had lasting consequences for the nature of Lutheranism, because his willingness to make compromises with political authorities, even when they were acting in an unchristian manner, provided the theological underpinnings of the accommodation many Lutherans would reach centuries later with the Nazi regime.

“A work of genius”

There are books devoted to the impact Luther had on religious music, and on politics, and on the sacraments, and on the German culture. And on his impact on the German language.

Indeed, Roper suggests that Luther’s most lasting achievement may have been the German Bible, an interesting assertion, given that he was the one who lit the flame of the Reformation. Perhaps, she holds the view that this cataclysmic change in western Christianity was going to happen one way or another, if not through Luther than through someone else.

The prose of Luther’s Bible, she writes, “shaped the German language, creating the modern vernacular as we know it.” His translation of the New Testament during an 11-week period in 1522 was “a work of genius.”

“Earthier”

The Reformation gave birth to two translations that shaped national languages. In English, it was the King James Version, carried out by a committee of scholars. The translation that Luther did by himself was the vehicle through which today’s German language was created. But the two versions are very different.

Roper says that the Luther Bible is set apart from earlier clumsy German translations by “his sense of the music of language.” She notes:

His style is direct and unadorned, using alliteration and the rhythm of everyday speech. He writes in a populist German, not in Latinate prose. This makes his translation very unlike, for instance, the English King James version, which is deliberately literary in style. Luther’s version is earthier, and his sentences shorter. This is a Bible designed to be read aloud and to be heard by ordinary people.

This style made it easier for a German believer, new to the reading of Scripture, to understand what was written. In addition, Luther prefaced each book of the Bible with “a short and brilliantly clear introductory exegesis” to spell out that meaning.

The result was that the German reader encountered the Bible through Luther’s theological lens — an experience that was heightened because the printing was such that there was no way to tell where the introductions ended and the Bible text began.

“Not done enough”

After centuries of books dealing with Luther’s anti-Semitism, usually arguing that he was simply parroting a common bias, Thomas Kaufmann, one of the world’s leading authorities on the Reformation, blew such equivocations out of the water in October, 2014, when he published Luther’s Jews: A Journey into Anti-Semitism (available in English in 2017).

It was a book, writes Roper, “that acknowledged Luther’s anti-Semitism once and for all, and which did not excuse it as a product of his times.” Suddenly, anti-Semitism was part of the German national debate for the first time since World War II, and on the eve of the 500th anniversary of Luther’s 95 Theses.

At that point, Roper was well into the final stretch run to the publication of Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet, in June, 2016. In that biography, Roper devotes seven pages to the subject but, in a later book, Living I Was Your Plague: Martin Luther’s World and Legacy, she acknowledges that she fell short:

I realized that I had not done enough to interrogate Luther’s anti-Semitism or to ask how far it extended into Lutheran theology. And I sensed that I needed to confront the less comfortable sides of his legacy.

In the later book, published in 2021, Roper included a chapter on “Luther the Anti-Semite,” a 34-page treatment that is nearly five times longer than the section in her Luther biography.

It’s rough reading. And, apparently, it was rough writing. Roper includes enough examples of Luther’s excrementary descriptions of Jews to make her point but indicates that there are many more.

“Its mobilization of revulsion”

Luther’s anti-Semitic writings, Roper notes, “are more extreme and have none of the humor that leavens his assault on the papacy, or his diatribes against individuals.”

Indeed, Luther’s anti-Jewishness wasn’t an expression of the common anti-Semitism of his time and place, a bias that asserted that Jews saw Christians as disgusting and unclean. It was something much more his own.

Fantasies this disturbing and deep belong to the kind of material I encountered when working on the witch craze [Her 2004 book Witch Craze: Terror and Fantasy in Baroque Germany]. They suggest that Luther’s anti-Semitism was linked to deep phobias buried in the unconscious, and go back to early infancy, connected to ideas about eating, the boundaries of the body, excrement, and to fears of dissolution.

What is most puzzling about Luther’s anti-Semitism, writes Roper, is that “it is animated by a deep recognition and identification.” Luther identifies with the Jews as God’s Chosen People and with the rabbis as the interpreters of the Bible — but he wants, needs, to claim those positions solely for himself and his new church.

All of this has had ramifications for Lutheranism down through the centuries and still does today. And Roper concludes this chapter:

Any serious consideration of Luther’s anti-Semitism must confront its extreme irrationality, its use of bodily imagery and its mobilization of revulsion. It has to recognize that Luther’s anti-Semitism went further than that of many of his contemporaries, and was not merely the expression of the age.

“Huge historical effects”

Anti-Semitism, music, language, culture, politics — any of these could be the focus of a book on Luther. Roper deals with all of these subjects and more, but her aim is on the man himself and what made him tick. And why his ideas clicked with the Christians of his era.

The “abiding focus” of her book, she writes, is Luther’s inner development:

How did he have the inner strength to resist the emperor and estates at Worms? What drove him to this point? …. Why did Luther, time after time, fall out with those with whom he had worked most closely, creating searing enmities and leaving his followers terrified that they might also incur his wrath? How did the man who had been convinced that “they won’t wish a wife on me” become the model of the married pastor?

Roper seeks to track the emotional changes in Luther that were caused by the religious changes he set in motion. And, also, it can be said, the religious changes that were spurred by Luther’s own emotions.

Luther’s personality, she writes, “had huge historical effects — for good and ill,” adding:

It was his remarkable courage and sense of purpose that created the Reformation, and it was his stubbornness and capacity to demonize his opponents that nearly destroyed it.

A professional historian

Roper doesn’t provide glib pontifications. In fact, she acknowledges that it might seem “foolhardy to attempt a psychoanalytically influenced biography” of Luther, running the risk of overestimating the role of a single person

in much the same way that sixteenth-century Lutheran hagiography did, making it impossible to understand why Luther’s ideas might have appealed to so many and how they created a social movement.

She is a professional historian who, in contrast to many previous writers, stands in no religious camp.

She approaches Luther as a man whose ideas and actions jolted his times and changed the course of history. She details those ideas and the controversies that they sparked but isn’t trying to judge the value or validity of any theological issues.

His theology from his character

Luther the man was a mess of contradictions, she writes.

Here is a man who made some of the most misogynistic remarks of any thinker, yet who was in favor not only of sex within marriage but crucially that it should also give bodily pleasure to both women and men….

A man of immense charisma, Luther’s passionate friendships were matched by equally unrelenting rejections of those he believed to be wrong or disloyal.

His theology sprang from his character … Luther’s theology becomes more alive as we connect it to his psychological conflicts, expressed in his letters, sermons, treatises, conversations, and biblical exegesis.

The man who emerges from the pages of Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet is one of a kind — angry and anxious, afflicted by doubts and rock-solid in biblical interpretation, funny and mean, troubled and transcendent.

For a reader of Roper’s biography, Luther is a fascinating person to spend time with. Never boring. Never at peace. Always unsettling.

Patrick T. Reardon

6.9.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.