In his more than four dozen novels, Terry Pratchett was often silly, witty, wacky and goofy. But he was also, always, serious.

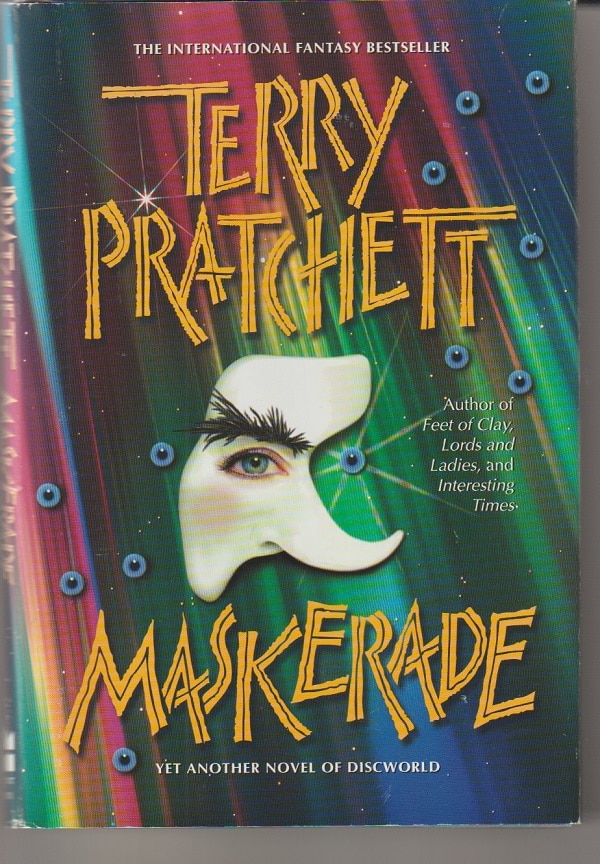

Pratchett’s delightfully humorous and endlessly readable books weren’t only aimed at getting a laugh. He employed them to wrestle with the deepest human longings, dreads and values, such as in this scene from his 1995 Discworld novel Maskerade.

Granny Weatherwax is at the at the Ankh-Morpork Opera House with her sidekick Nanny Ogg in order to (a) lure back Perdita X. Nitt, nee Agnes Nitt, a sister witch from Lancre who has come to the big city to become an opera star, and (b), incidentally, solve the mystery of a series of murders at the Opera House. (If this sounds like a take-off on the Phantom of the Opera story, it is — except, of course, for the witch part.)

Anyway, at one point, Granny is ruminating about opera as a performance is underway:

There was fear here. It stalked the place like a great dark animal. It lurked in every corner. It was in the stones. Old terror crouched in the shadows. It was one of the most ancient terrors, the one that meant that no sooner had mankind learned to walk on two legs than it dropped to its knees. It was the terror of impermanence, the knowledge that all this would pass away, that a beautiful voice or a wonderful figure was something whose arrival you couldn’t control and whose departure you couldn’t delay.

The old terror of human impermanence — it doesn’t get more serious than that.

“TEND TO LOSE CONCENTRATION”

Since there is a killer loose in the opera house, there are a good number appearances of Death, a character, all skull and bones, who shows up in nearly every one of Pratchett’s Discworld books but rarely as often as in Maskerade.

For instance, Dr. Undershaft, the chorus director of the opera, suddenly discovers, in a sort of out-of-body way, that he’s been murdered and is now talking to Death:

WE MUST GO, said Death.

“But he just killed me! Strangled me with his bare hands!”

YES. CHALK IT UP TO EXPERIENCE.

“You mean I can’t do anything about it?”

LEAVE IT TO THE LIVING. GENERALLY SPEAKING, THEY GET VERY UNEASY WHEN THE DECEASED TAKES A CONSTRUCTIVE ROLE IN A MURDER INVESTIGATION. THEY TEND TO LOSE CONCENTRATION.

“I AM IMPRESSED”

Death, in Pratchett’s books, is usually very droll, and his scenes are often comic. Even so, they frequently deal as well with significant stuff. After all, this is Death we’re talking about.

Death, in Pratchett’s books, is usually very droll, and his scenes are often comic. Even so, they frequently deal as well with significant stuff. After all, this is Death we’re talking about.

So, when Granny is asked to help a baby dying of Red Bugge, she spends the night with the boy in the stable where a cow is similarly stricken. She knows who to expect and knows she wants to bargain for the life of the baby in exchange for the life of the cow. Of course, as a mortal herself, this meeting with Death could have bad ramifications for her.

Granny folded her arms and stared calmly at the visitor, meeting his gaze eye-to-socket.

I AM IMPRESSED.

“I have faith.”

REALLY? IN WHAT PARTICULAR DEITY?

“Oh, none of them.”

THEN FAITH IN WHAT?

“Just faith, you know. In general.”

Talk about serious stuff. This idea that humans need faith even if they don’t ascribe to any of the institutional religions pops up throughout Pratchett’s books.

What faith means to him here and in the rest of his books is a kind of hope. A willingness to wake up every day and go about life, despite all the oppressive things that afflict people. A belief in the value of living a full life, accepting the dread at the heart of existence but also reaching for what’s right and good.

It’s deadly serious.

“Indefinitely postponed”

But not deadly dull.

Here are some examples of Pratchett’s wit and sharp observational skills. The first has to do with Granny Weatherwax’s staunch independent way of living through which she shows that she doesn’t need anyone:

Of course, Granny Weatherwax made a great play of her independence and self-reliance. But the point about that kind of stuff was that you needed someone around to be proudly and self-reliant at. People who didn’t need people needed people around to know that they were the kind of people who didn’t need people.

And here’s one describing Walter Plinge, the Opera House handyman who struggles to get his sentences out and whose body is oddly configured:

He had a unique stride: it looked as though his body were being dragged forward and his legs had to flail around underneath it, landing wherever they could find room. It wasn’t so much a walk as a collapse, indefinitely postponed.

Perdita, who is still often Agnes in her head, is what Americans euphemistically call a big-boned woman. In fact, she’s so big-boned that, during a performance, she’s used only to dub in the voice for a pretty little thing who gathers male attention like flies around honey. She recognizes her disadvantage:

She’d heard somewhere that inside every fat woman was a thin woman trying to get out*…

[at the bottom of the page] * Or, at least, dying for chocolate.”

At another point, a crowd of stage people has chased the killer and jumped on him, swinging and landing blows, even though he has skillfully slipped away:

The kicking and punching stopped only when it became apparent that all of the mob was attacking was itself. And, since the IQ of a mob is the IQ of the most stupid member divided by the number of mobsters, it was never very clear to anyone what had happened.

A final example: Agnes finds Granny and Nanny exasperating because, without exchanging words, they are able to work in tandem to persuade her to come back to Lancre:

Of course, there were plenty of other things — the way they never thought that meddling was meddling if they did it; the way they automatically assumed everyone else’s business was their own; the way they went through life in a straight line; the way, in fact, that they arrived at any situation and immediately started to change it.

Maskerade is a very good Terry Pratchett book — which is saying a lot.

Patrick T. Reardon

6.25.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.