I realized recently that I don’t know how to think about the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

What I mean is that the Getty, founded in 1974 by the petroleum industrialist just two years before his death at 83, is one of the great art museums of the world but also one of the newest. And absolutely the wealthiest.

The Louvre in Paris and the Hermitage in St. Petersburg have been in existence for centuries. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Art Institute of Chicago date back to the 1870s, and the National Gallery in London will have its 200th birthday next year. Yet, the Getty, able to pay top dollar for great art for more than half a century, has a collection that rivals all of those.

Getty’s personal collection was the basis for the museum, but I don’t have any idea how strong the art he owned was. I did see a passing reference that Getty never wanted to pay full price for anything in his lifetime which may say something.

His museum inherited $1.2 billion from his estate in 1982 (the equivalent of about $3.7 billion today). As of today, its endowment has grown to nearly $8 billion, making it richer than any other art institution in the world.

In 2003, the museum published its fifth edition of Masterpieces of Painting in the J. Paul Getty Museum — followed in 2019 by a later edition — and the 128-page book presents 68 arresting paintings from such artists as Rembrandt, Turner, Renoir, Munch, Fragonard and Correggio.

Reading the book, I noticed two trends in collection, and I wondered if they were trends that Getty had started or patterns in the buying habits of the people running the museum. (Of course, it could be that the paintings that I’m talking about just happened to be what’s been available over the past 50 years, or there’s some other reason.)

In any case, one of the trends I’d call Eros. The other, Portraits.

Eros – Farewell

Two of the paintings show Venus trying to keep Adonis from leaving her arms to go off to hunt — where he will die after being gored by a boar. The Titian work from the 1560s makes Venus’s nudity the focus of the painting, giving a tangible sense of her arms, legs, back and buttocks reaching for her lover.

Eighty years later, the Frenchman Simon Vouet seems more interested in the flowing fabrics of the lovers and in the somewhat feminine face and hair of Adonis.

Another Frenchman Jacques-Louis David portrayed a similar but less fatal scene in his 1818 work The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis. Here it’s Telemachus’s nudity that is front and center while Eucharis is more demurely clothed though in a peak-a-boo, side-snapped garment.

Eros – Lust

Venus shows up again in The Return from War: Mars Disarmed by Venus, painted in 1610-12 by the Flemish artists Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder, who created at least a dozen works together during their careers.

Here, Venus’s soft, creamy skin, used to entice Mars to stay, is contrasted with the armor and armaments of the war-god.

One of the more startling works involving Venus is Mars and Venus, Surprised by Vulcan, painted in 1606-1610 by the Dutchman Joachim Wtewael. Not only is everyone in the painting naked, but the work tells the story of Vulcan catching his wife in the act of adultery with her lover. Wtewael leaves very little to the viewer’s imagination with his graphic depiction of the scene.

A contrast with this very earthy painting is the Frenchman Jean-Honore Fragonard’s piece The Fountain of Love, a much more atmospheric depiction of lust. As the museum’s book comments:

Irradiated by moonlight, two lovers surge out of a murky forest toward the fountain of love. Their straining necks and parted lips reach for a glistening chalice, borne by two putti, filled with erotic waters.

So, the questions I’m left with include: Why so many Venus paintings? Why so much sex? Obviously, any great museum would have a lot of such pictures. But, among the 68 works in this book, 12 — including one that alludes to incest (Lot and His Daughters by Orazio Gentileschi around 1622) — fit into the category of eros.

Portraits – Ordinary

Even more — 20 — are portraits, including one of a piebald horse. In some ways, these are even more compelling than the sexy paintings because their subject is human character, such as Portrait Study, painted around 1818-1819 by Theodore Gericault, a Frenchman.

The eyes and the set of the otherwise ordinary face communicate a great many emotions. So, too, in a less spectacular way is Saint Bartholomew, created in 1661 by Rembrandt.

In its commentary on the image of a “stolid, rather pensive, and very ordinary” man, the museum writers note:

The idea that a common man could be identified with a biblical personage and thereby lend a greater immediacy to Christ’s teachings would have been in keeping with the religious atmosphere in Amsterdam at the time. Saint Bartholomew is represented with a mustache and a broad, slightly puzzled face.

These two contrast in a rich way with the 1885 portrait of five-year-old Jeanne Kefer by Fernand Khnopff. The book’s writers comment:

Her back pressed against the door, Jeanne is dressed for the world and about to embark, but stands frozen in place, her gaze impassively fixed on us. With photographic precision, Khnopff situates Jeanne in a highly structured, yet spatially ambiguous composition.

Portraits – Thoughtful

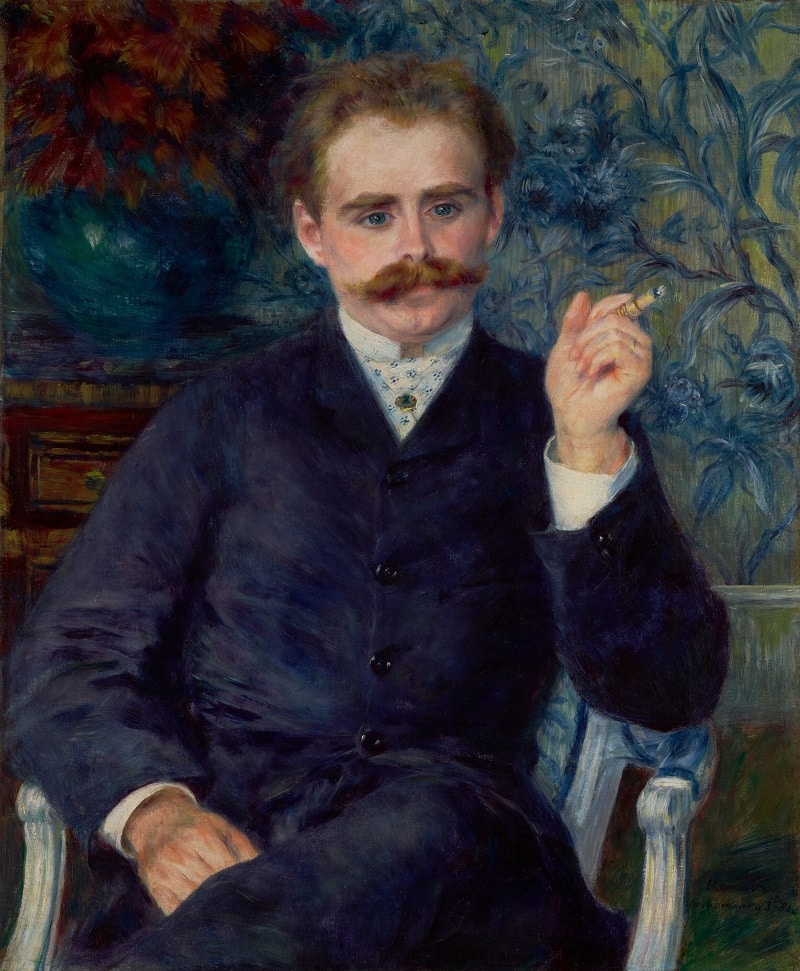

There is a lot going on in the following three portraits from the nineteenth century: Albert Cahen d’Anvers by Renoir in 1881, Young Italian Woman at Table by Cezanne in about 1895-1900 and Louise-Antoinette Feuardent by Jean-Francois Millet in 1841.

Albert, a composer, comes across, to me, as a self-contained dandy, lost in his thoughts…or is it music?

As for the seemingly brooding Young Italian Woman, the museum’s commentary notes:

Cezanne’s primary interest in this work, however, resides in form rather than psychology. He revels in constructing the volumes of the woman’s head, body and garments.

Even so, he does capture a moody thoughtfulness in the woman, maybe weariness as well. Given Cezanne’s preoccupations, she certainly seems solidly bodied.

By contrast, Millet’s Louise-Antoinette communicates a fragility under the surface. There is a melancholy feel as well. All three of these subjects are thoughtful, but I have the sense looking at Louise-Antoinette that her thoughts are more troubled, more unsettling.

Patrick T. Reardon

4.17.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

I am in complete disagreement that the Getty Collection Rivals the works of the aforementioned Museums in this article. The works are decidedly of a mediocre quality compared to works in the Louvre in Paris, the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the National Gallery in London. Those collections are A-list. The Getty’s collection feels B-list at best.

Thanks for your comment. You may know better than I do.