Richard Carrington has been called a naturalist and a naturalist-historian. But, above all, he’s a writer.

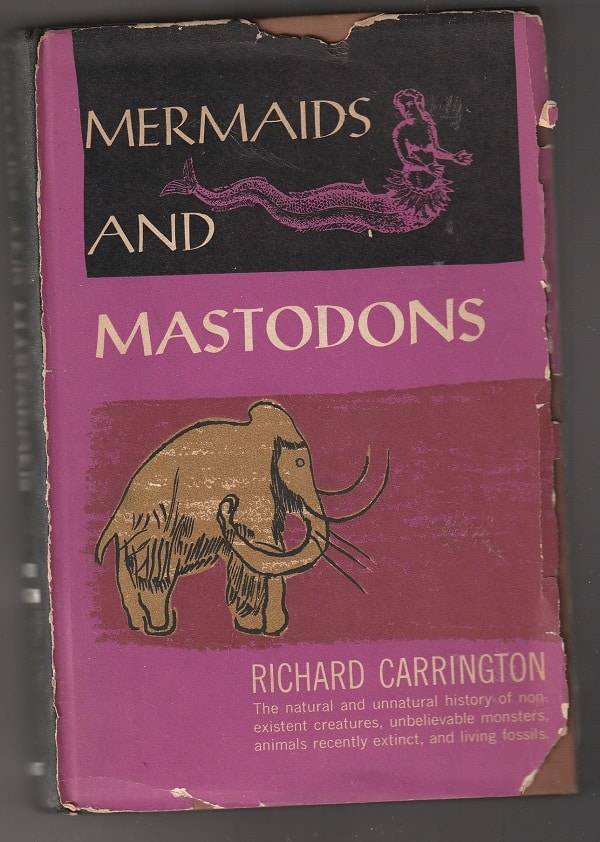

In his 1957 Mermaids and Mastodons, he writes about creatures and events from millions and millions — and millions — of years ago with verve, zest and great delight.

Carrington takes deep enjoyment from the stories he tells of the far distant worlds that existed before evolution brought us to our present place and from the, at times, clumsy and, at times, ingenious ways that humans have used to figure out what those distant worlds were like.

He is captivated by the workings of Nature in all their complexity and mystery, all their odd quirks, all their seemingly endless variety.

Enthusiastic and passionate, in a droll British sort of way, Carrington entertainingly shares his excitement with the reader. It’s as if you’re sitting at the club with him of an evening, listening to him bubble over about the wonders that he has found in the vast range of scientific volumes that he has consulted.

Indeed, you don’t have to be a science nerd or, for that matter, know much about the sciences of studying the far ago ages of the Earth to enjoy your time with him.

Carrington is writing for the reader, like me, who just wants well-told, factually rooted tales about the human condition. Because that, at bottom, is what the study of the past worlds is about — thinking about how humans came to be here and now in the ways we are.

“A contingency that eventuated”

Carrington has fun writing about all of this, and the reader has fun reading it.

He loves, for instance, the often convoluted, idiosyncratic language of the scientists of the 17th and 18th centuries. In a chapter on dinosaurs, he quotes naturalist William Foulke of Philadelphia about the difficulty of removing dinosaur bone fossils from the stone in which they were encased:

A sketch was made of their position, and some measurements were taken of them, in anticipation of the contingency of their fracture in the attempt to remove them.

After which, Carrington writes:

Fortunately, as Foulke himself might have expressed it, the fracture of the bones was not a contingency that eventuated.

“Floats naked”

In a chapter on the quagga, a now extinct cousin of the zebra, Carrington describes the early search in southern African for one or more live animals, singling out Swedish naturalist Andrew Sparrman whose account of his 1775 trip showed him to be “a man of considerable intelligence, charm and humor.”

This was an era when each chapter in a book such as Sparrman’s would begin not just with a title but also with a point by point summary — kind of a pre-cap — of the chapter’s text.

And this is where Sparrman delights Carrington who writes:

How, for instance, can one resist chapter synopses [in Sparrman’s book] that contain such headings as these: ‘Hires a bastard, a man of family, for his guide. Is lodged and entertained by a slave. Curious method of serving at the same time God and mammon. The author very ungallantly neglects to requite the services of a female slave. A slave’s revenge on his niggardly master. The author in danger at a rich widow’s house of being kicked out of doors, on his hat being discovered with the brim stuck full of beetles. Floats naked over the river to an islet on a bundle of palmites plants, in order to botanize there. Makes a sexton and his wife happy by prognosticating the death of the latter. . . .’ And so on, in the same vein.

“A most surprising thing”

But Carrington is no slouch himself when it comes to turning a phrase.

For instance, he discusses at one point the New Zealand bird Notornis, “a large bird of the rail family, looking like a moorhen but weighing as much as a goose.”

In 1847, parts of its skeleton were first discovered on North Island by Walter

Mantell, the son of the famous Dr Gideon Mantell who had discovered the dinosaur Iguanodon. These bones, in a sub-fossil condition, were sent to London and were correctly identified as belonging to a previously unknown species of gallinule and given the name Notornis mantelli in honor of its discoverer.

“After which no one thought very much more about it.”

Ah, but then…

Then a most surprising thing happened: the fossil Notornis came to life. In 1849 a party of sealers was camped on Resolution Island, near the south-west end of South Island, when one of their number brought in a living example of the bird. Of course they had never heard of the Notornis… and being practical men they promptly wrung the creature’s neck and popped it in the pot.

Nevertheless they must have been deeply impressed by its beautiful indigo blue and malachite green plumage, for they persevered the skin, which eventually, by a great stroke of luck, was acquired by Walter Mantell and despatched to London.

There, experts determined that this had been a living example of the Notornis.

A small colony

Despite a couple sightings, the live bird disappeared for nearly a century until, in 1948, a scientist found a small colony of the birds near a lake he’d just discovered although it had been well-known to the Māori people.

Very quickly, New Zealand made the whole region of 435,000 acres, or nearly 700 square miles — or about half as big as Rhode Island — a nature reserve to protect the species.

Carrington was writing 65 years ago, and a quick check of the internet indicates that the Notornis is still with us although still considered extremely endangered.

That’s good because Carrington included the bird in a chapter titled “Fossils of Tomorrow.”

“I could not see the sun”

Carrington is not afraid to show his emotions, particularly his anger at the willful human destruction of creatures, even to the point of extinction.

The passenger pigeon is a prime example, and his chapter on the bird is titled “The Story of a Massacre.”

This bird was once not just common but “the best known bird in the whole of North America.” Larger than other American pigeons, some individuals exceeding one and a half feet in length from beak to tail.

It was conspicuous also by its color, the male having the upper part of the head, the back and wings colored a delicate shade of blue, while below, the throat and breast were reddish fawn, shading to white on the abdomen. The female was less vividly marked, but the distribution of the colours was the same; she was a smaller and somewhat more subdued replica of her mate.

The first European to report seeing a passenger pigeon was the French explorer Jacques Cartier who spotted them in 1534 on the banks of the St. Lawrence River. Quickly, they were known for traveling in vast crowds in their migrations..

As early as 1605 the French explorer Samuel de Champlain was talking of ‘an infinite number of Pigeons’ he had seen along the coast of Maine, while Josselyn, another Frenchman, wrote in 1672: “I have seen a flight of pigeons that to my thinking had neither beginning nor ending, length nor breadth, and so thick I could not see the sun.”

“Dung some inches thick”

Naturalists were particularly impressed, such as, Mark Catesby who, in 1731, wrote in The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands:

“Of these pigeons there come in Winter to Virginia and Carolina, from the North, incredible Numbers; insomuch that in some places where they roost (which they do on one another’s Backs) they often break down the limbs of Oaks with their weight, and leave their Dung some Inches thick under the Trees they roost on. Where they light, they so effectually clear the Woods of Acorns and other Mast, that the Hogs that come after them, to the detriment of the Planters, fare very poorly.

“In Virginia I have seen them fly in such continued trains three days successively, that there was not the least Interval in losing sight of them, but that some where or other in the Air they were to be seen continuing their flight South. … In their passage the People of New York and Philadelphia shoot many of them as they fly, from their Balconies and Tops of Houses; and in Mew-England there are such Numbers, that with long Poles they knock them down from their Roosts in the Night in great numbers.”

“Exceptionally beautiful”

There is much more to Mermaids and Mastodons, including a discussion of the discovery of mastodon bones and an examination of the factors that resulted in the mermaid myth in many human cultures.

And the creatures that helped to spur on the myth of the phoenix, purple herons

But Carrington has a place in his heart for the myth as much as the actual herons. “The phoenix legend…is a very ancient one, and as it is also exceptionally beautiful, I hope I may be forgiven if I recount it at some length.”

He writes that, according to tradition, there could be only one phoenix in the world at a time. It lived in paradise which, for our ancestors, was “a land of infinite beauty lying beyond the horizon towards the rising sun.”

Every thousand years or, depending on the version, some other period, the phoenix would be oppressed by having lived so long and would set out for the mortal world.

It flew westward over the jungles of Burma and Assam, the hot plains of central India, and the mountains of Afghanistan, until it came at length to the spice groves of Arabia. Here it paused in its journey to load its wings with a sweet-perfumed cargo of laudanum and frankincense and other aromatic plants, and then flew on until it came to the coast that is named after it, the coast of Phoenicia. in Syria, running northwards from Mount Carmel.

There, the phoenix built its nest in the topmost branches of the tallest tree, using all those aromatic plants, and, as night fell, it settled down to await the dawn and its death.

The hours of darkness passed slowly, but at last die sky lightened and the sun soared upwards over the horizon. As it did so the phoenix turned to the east and sang a song of such surpassing beauty that even the sun god himself paused for a second in his chariot to listen. And in that moment the whole Universe, the rolling Earth and the wheeling stars, stood still with the sun god and listened to the sweetness of the phoenix’s song.

Then as suddenly as he had paused the sun god whipped up his horses again. Sparks flew from their hooves and from the vast corona of fire that encircled his head. Some of these sparks fell on the nest of the phoenix, and catching the sweet-smelling herbs, turned it to a blazing aromatic funeral pyre. And thus in song and perfume and fire the phoenix ended its thousand years of life.

A beautifully related myth in a beautifully written book.

Patrick T. Reardon

8.9.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.