In the 1850s, Swedish writer Fredricka Bremer visited to Chicago and, to say the least, was not impressed.

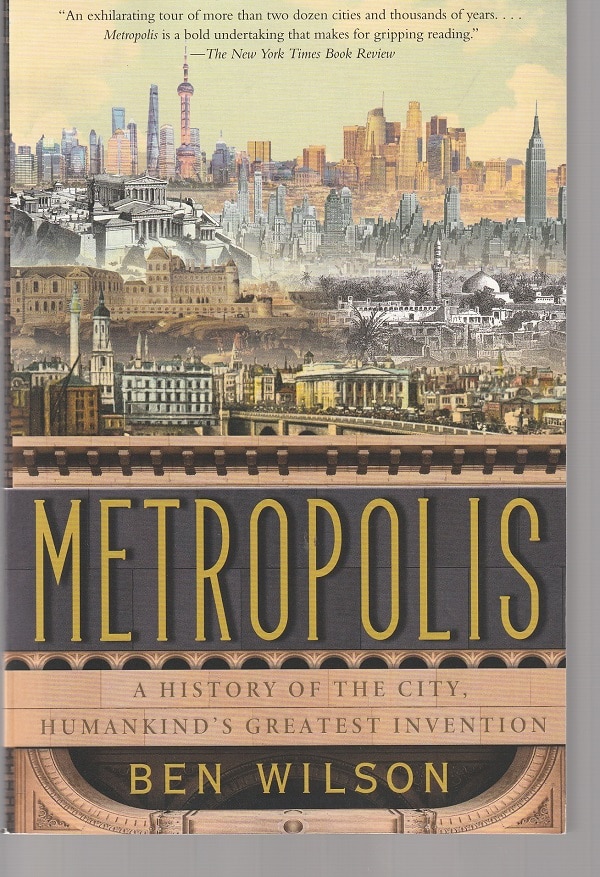

Ben Wilson notes in his sweeping and astute Metropolis: A History of the City, Humankind’s Greatest Invention that boosters promoted Chicago as “Queen of the Lake.” But Bremer dubbed it “one of the most miserable and ugly cities,” one that, “sitting there on the shore of the lake in wretched dishabille,…resembles rather a huckstress than a queen.”

Wilson writes that a French visitor “felt the stench of Chicago grab him by the throat as soon as he arrived.” And the noise! Every outsider complained about the noise:

“Visitors commented that Chicago sounded like no other city in the world with the ‘deep hollow roar of the locomotive and the shrill scream from the steamboat’ mingling with the clatter of industry, the squeals of thousands of hogs about to be slaughtered and the uproar of the incessant crowds. Others experienced the power of Chicago throbbing ‘with an unbridled violence.’ ”

And that was the experience of visitors. Chicagoans — especially those who lived and worked away from the fancy streets and neighborhoods — had to put up with much worse, such as the roadside gutters filled with human and animal waste, “leaving standing pools of an indescribable liquid.” Wilson writes:

“These ditches were so vile that ‘the very swine turn up their noses in supreme disgust.’…Built on level ground over hard clay, Chicago was a damp and polluted city, with so-called ‘death fogs’ emanating from piles of ordure. The river ran with sewage and industrial effluence.”

Such pollution made Chicago and Manchester, its sister “Shock City” in England, the deadliest on earth for the poor, near poor or working class. In Chicago, that meant the vast numbers of immigrants who formed the majority of the population. Wilson writes:

“Nowhere in the mid-nineteenth century had a death rate comparable to these beshitten industrial cities. From the 1830s the Asian cholera tore through slums. In 1854, 6% of Chicago’s population succumbed to the epidemic, the sixth in a row that the city had been devastated by the disease.”

And yet… And yet…

The genius of Metropolis

It is the particular genius of Metropolis — originally published last year and now available in paperback — that Wilson looks at 6,000 years of urban history in from a comprehensive, 360-degree perspective, taking in the full gamut of human endeavor, including culture, economics, politics, sociology, psychology, engineering and architecture. And that he writes about it with the gusto of a lover who recognizes the beauties and the warts of the beloved.

Wilson, a British historian, writes that the first city Uruk in what is now Iraq had a culture “characterized by demolition and dynamism” and driven by “a collective endeavor to create works of magnificence.”

And about the first mega-city Rome with its hundreds of imperial bathhouses which were much more than simply places to get clean:

“People went to conduct business, argue about politics, gossip and solicit dinner invitations. They went to see and be seen. They ate, drank, argued, flirted and, occasionally, had sex in alcoves; they scrawled graffiti on the marble….The baths offered a unique and all-encompassing urban and urbane experience. Above all it was a communal activity.”

More than a thousand years later, London had its own version of such meeting places — coffeehouses which “provided a vital function of cities, supplying the motive and location for spontaneous encounters and the emergence of informal networks.” These were places where members of the otherwise rigidly segregated classes could rub elbows and talk to each other. They also were a step in making cities more livable.

“London offered myriad opportunities for the sociability that made people more refined. In turn, civility made city-living easier because it provided the lubrication for interactions between strangers in the congested urban environment.”

Broader urban context

Here, as he does throughout Metropolis, Wilson steps back from his examination of London to put civility in the broader urban context. He notes that a city “is one of the miracles of human existence,” and adds, “What prevents the human ant heap from degenerating into violence is civility, the spoken and unspoken codes that govern day-to-day interactions between people.”

In Metropolis, Wilson closely details the stories of 20 some cities going back to 4,000 BC and fits dozens more into his discussion. He gives an account of a particular city at a particular time, and, in each case, he relates how other cities have reflected the same elements.

He describes, for instance, Lubeck in Germany as one of many early modern cities of war and then goes further to analyze other aspects of death and violence as well as the technological breakthroughs that occurred in the arms race of that era: “Urbanization in Europe surged as a result of the entrepreneurship of its people, to be sure; but its dynamism also came from less positive sources: The Black Death, Crusades, endemic warfare and deadly intra-city rivalries.”

“Two meals a day”

Wilson is a huge fan of cities, seeing them as the future of humanity. Yet, as his description of the harsh realities of mid-nineteenth century Chicago indicates, he is aware of their ugly and dangerous sides.

“The myth of Babylon echoes down the ages: as stunningly successful as they are, cities can crush the individual. For all that is compelling about the metropolis, there is a lot that is monstrous too.”

Both beauty and the beastly are woven into the fabric of a city as Wilson shows time and again in Metropolis.

Take his descriptions of the odors, noise and “death fogs” of Chicago and similar grim realities in Manchester in the mid 1800s. These are in a chapter titled “The Gates of Hell?”

That question mark is key. Yes, Wilson writes, cities can be claustrophobic and blighted and chaotic. But, for someone fleeing rural poverty, they offer hope. That’s why people went to Manchester and Chicago.

“The peasants of nineteenth-century Ireland fled misery and famine for better lives in the slums of Manchester and Chicago, taking their chances with cholera and typhoid. As an Irishman put it, living and working in Manchester gave him a chance to eat two meals a day.”

“Messy urbanism”

Wilson writes about the reality of “messy urbanism.” Utopian schemes for cities always fall prey to human nature and the human tendency to foster chaos.

His final chapter discusses the most modern mega-city Lagos in Nigeria, with a population three times larger than London and squeezed into an area two-thirds London’s size — a city that is “vast, unfathomable, noisy, dirty, chaotic, overcrowded, energetic, dangerous.”

Despite its many troubles, Lagos, Wilson writes, is expected to double in population to 40 million people by 2040.

Those people will be going to Lagos for the same reasons people have gone to cities for six millenniums: Hope and opportunity. That’s the lifeblood of any metropolis.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.7.22

This review originally appeared at Third Coast Review on 12.8.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.