Major-General James Wolfe, commander of the English forces at the Plains of Abraham on the morning of September 13, 1759, had already been shot twice in the battle against the French forces outside the walls of Quebec — once in the wrist and once in the groin. Roch Carrier writes about what happened next:

Despite his two wounds, Wolfe dismounted from his horse. His long body erect in its stiff scarlet tunic, he stood between the Louisbourg grenadiers and the “butchers” of the 28th Infantry Regiment, waiting for the white smoke from the musket fire to dissipate so he could see what damage [those two English units] had inflicted. A ball shattered his ribs. He staggered, but did not fall. He sat down. Two lieutenants ran up, another grenadier came to their aid, and they carried their major-general to a depression in the ground.

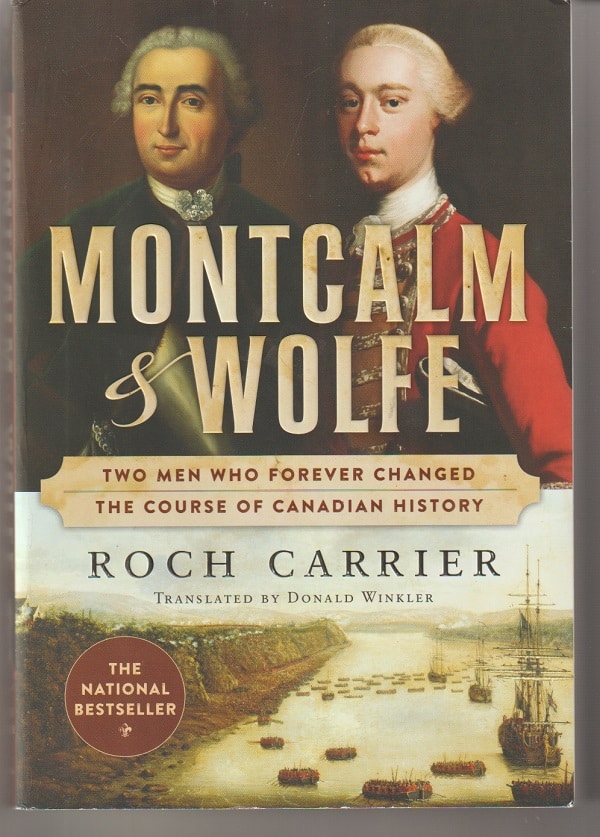

This account comes on page 285 of Carrier’s 315-page book Montcalm and Wolfe: Two Men Who Forever Changed the Course of Canadian History, published in 2014.

Two paragraphs later, on the next page, Carrier tells of the efforts of French officers, including Lieutenant General Louis-Joseph, Marquis de Montcalm, the French military commander in Canada, to re-form the ranks of their troops for whom “panic was stronger than discipline.” He writes:

On his horse, sword in hand, Montcalm waved his arms, ordered his companies to rally. His arms extended, he tried to intercept the escapees. Two balls hit him, one on the thigh, the other in the groin. He was about to fall from his horse, but two of his men placed him back in the saddle.

Novelistic techniques in the service of non-fiction

Roch Carrier is a French-Canadian novelist and short story writer. Fiction is his usual field. With Montcalm and Wolfe, however, he has kept his feet firmly in non-fiction, filling his pages with facts and stories about his two subjects, going back to their births.

He doesn’t make up scenes or dialogue. Nonetheless, there are many other techniques of the novelist that Carrier employs in presenting all those facts and stories.

For instance, he writes about the two men in parallel, going back and forth, from one to the other, relating how their lives were unfolding and their careers were developing. Early on, their paths are very distant from each other. As military men, they operate in different areas, never at the same place at the same time.

However, in one of those quirks of history, both men were presented to King Louis XV of France — Wolfe with other English guests on January 10, 1753, and Montcalm on February 14, 1756, after agreeing to become the military commander in Canada.

Intensifying momentum

In this back-and-forth description of the two lives, Carrier writes primarily in simple declarative sentences. This fact, this fact, this fact.

He avoids analysis, particularly anything that recognizes what is going to happen outside the walls of Quebec. In doing this, he is mirroring the experiences of the two men, neither of whom had any glimmer of the other’s existence nor of their linked fates until late in their stories.

Of course, the reader knows, and that gives the storytelling a sharp edge of expectation.

The result is that Carrier’s narrative has a momentum that builds moment by moment in intensity. Here is where his structuring of the tale as a novelist has its strongest effect. The reader is drawn deeper and deeper into the story as the lives of the men, like two arrows on a map, approach nearer and nearer each other.

Giving form to history memory

Montcalm and Wolfe never met, and I’m thinking that, in their lives, the closest they ever came to each other was there on the battlefield.

Carrier doesn’t say this, but the structure of his book and his storytelling suggests it. After all, he has the two men fatally wounded within two paragraphs of each other.

From my other reading about the battle, I have the sense that Wolfe was shot somewhat earlier than Montcalm, and I’m not sure anyone can say, in fact, how close the two men came to each other on the Plains of Abraham.

Carrier is careful not to violate the facts of the story when he tells of the shooting of the two men so close together in his text.

He’s giving form to — reflecting — the way the battle has come down to us in history.

Drum beats to a crescendo

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham determined the future of Canada. The far northern reaches of North America became English because of the way that battle played out. Not only that. The battle had important implications for world history.

As historian D. Peter MacLeod notes in his 2008 Northern Armageddon: The Battle of the Plains of Abraham and the Making of the American Revolution, the victory of the English removed French Canada as a threat to the American colonies, thereby freeing the colonies of the need for British protection. Thus, opening the way for the move to independence.

Yet, for all its importance to history, the battle is remembered on an emotional level because both of the commanders lost their lives in the fighting — Wolfe, minutes after he was struck down, and Montcalm, lingering to die early the next morning.

While MacLeod uses his book to tell the story of the soldiers, sailors and civilians who took part in battle, Carrier is laser-focused on the two commanders. His book tells the drum beats of their lives that reach a crescendo when they are fatally shot.

The diminuendo

And then the diminuendo.

First, Carrier describes the burial of Montcalm’s body:

At eight o’clock, a horse pulled a wagon that carried the coffin of the Marquis de Montcalm. On every street, on either side, there were collapsed walls and sections of roofs, charred beams and floors….Even the sky seemed sad. Holding a few lanterns, men, women, and children, in tears, followed the coffin…

And, following the funeral service, the coffin was buried in a bomb crater in the chapel of the Ursuline nuns.

Then, he describes the movement of Wolfe’s body:

Major-General Wolfe’s body, transported to Pointe Levy, was embalmed in the church that had been requisitioned to serve as the military hospital. Then it was taken to Ile Madame, where the Royal William was moored. The cannons of Quebec saluted his remains with thundering solemnity…On September 25, the warship set sail for England.

In England, in Westminster Abbey, a monument in the memory of Wolfe was unveiled in 1773 with these words in marble: “Major-General and COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF of the British Land Force on an Expedition against Quebec.”

In France, officials in 1761 agreed to place a monument on Montcalm’s tomb, and Carrier reports that these were the lines written to honor his memory:

He made up for

Fortune with courage, and for the number of men

With skill and effort.

For four years, he delayed through his measures

And his valor, the imminent loss of the colony.

Montcalm is memorialized as the loser. He’s honored for holding back the loss for four years, and the inscription identifies the loss of the colony as unavoidable.

But Montcalm is still the loser. And Wolfe, the winner. And that is how history remembers them.

Patrick T. Reardon

5.5.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.