In the middle of his account of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham — one of the most consequential events in world history — D. Peter MacLeod writes about French bullets bouncing off of the chests of British soldiers.

This was just as the battle was starting. The French troops, on the orders of Marquis Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, were charging down from the slopes of Buttes-a-Neveu toward British soldiers arrayed in long lines across the plain. They had been arranged there by Gen. James Wolfe in expectation — and in hopes — of Montcalm’s attack.

Montcalm and Wolfe, the opposing commanders in this battle, would die from wounds suffered this day, September 13, 1759. They had set the stage for the violence that was about to unfold — and then, beyond their power, it happened. MacLeod writes:

Between the moment that Montcalm ordered the French army to charge down the Buttes-a-Neveu and the moment that Wolfe led a charge down the side of Wolfe’s Hill, the generals remained effectively invisible. They issued no dramatic orders to fire, stand, or retreat and exercised no discernible influence over the course of events.

“Thousands of individual decisions”

They set the stage, but then, in part because Montcalm lost control of his troops, the battle was fully in the hands of those doing the fighting. Again, MacLeod:

The British victory on the Plains of Abraham turned, first, upon Wolfe’s ability to overcome the geographic obstacle posed by the Quebec Promontory, which allowed his army to actually reach the plains and, second, upon a single order by Montcalm that effectively ceded command to his soldiers.

These soldiers in turn made the thousands of individual decisions that determined the result of the battle.

As he writes further, while Wolfe made the battle happen, “thousands of French soldiers and Canadian militiamen determined its course and outcome.”

A huge cast of characters

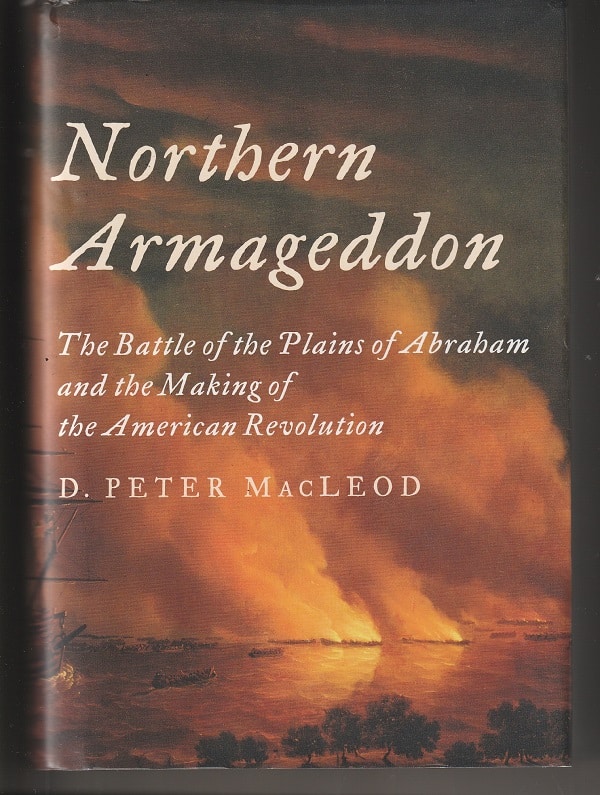

MacLeod’s 2008 account of the fight — Northern Armageddon: The Battle of the Plains of Abraham and the Making of the American Revolution — is a story of the soldiers, sailors and civilians who took part in struggle throughout the summer of 1759 for control of Quebec. And of Canada. And of North America.

Indeed, at the start of the book, MacLeod presents an 11-page section titled “The People of 1759,” listing some 170 participants who show up in his text. That’s a huge cast of characters to handle while also telling the complex political, geographical, social and demographic stories of the campaign, but MacLeod pulls it off with high achievement.

Northern Armageddon, published in Canada in 2008 in and in the U.S. in 2016, is history-writing at its finest — a nuanced, multi-layered, deeply researched narrative recounts the battle and all that led up to it and all that followed from a multitude of perspectives and angles.

This is, as it were, the battle in the round.

The usual story

And it’s quite a contrast to the way the story has usually been told in earlier books about the Plains of Abraham — as a clash between two mighty generals.

Montcalm And Wolfe, for instance, was the title of the magisterial 1884 account of the fight by American historian Francis Parkman. The English language title of the 2014 history by the major French Canadian novelist Roch Carrier is Montcalm And Wolfe: Two Men Who Forever Changed the Course of Canadian History.

This tight focus on the two commanders is understandable for a number of reasons.

For one thing, until recently, the tendency among historians has been to discuss battles from the perspective of the generals — what they did, why they did it, why they were successful, why they were defeated. That’s a relatively easy story to tell since generals produce a great amount of paperwork in terms of orders, reports, diaries and such that are available to researchers. Also, having two main characters simplifies the storytelling and gives a lot of room for man-against-man dramatics.

For another, this approach fits into the Great Man theory of history. It’s only the powerful people — men and women — who really steer events, such as presidents and queens, business titans and inventors, dictators and generals.

But, even more important, it seems to me, is that fact that Wolfe and Montcalm died in leading their troops. Talk about romantic. Talk about dramatics.

A century and a half after the battle, the death of Montcalm was memorialized in a relatively small painting by Marc Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté, now in Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec. It’s 1.8 feet by 2.8 feet, or five square feet.

But it’s little known compared to much-reproduced The Death of General Wolfe, a five-foot-by-seven-foot painting (35 square feet) executed in 1770 by Benjamin West and now in the National Gallery of Canada. In it, more than a dozen soldiers crowd around Wolfe who shows no sign of any bloody wound and, looking up to heaven, appears to be swooning.

In a book with a great deal of action, MacLeod devotes two of his 323 pages of text to the deaths of the two men.

“Almost spent”

He is much more interested in putting the battle into perspective in order to give the reader a strong feel for what the experience was of those who took part.

That, for example, is why he writes about bullets bouncing off British chests.

What happened was that, because of the uneven terrain and heavy brush and their downhill run, the French columns heading toward the British lines lost their cohesion. They weren’t moving as tightly organized units but more like a mob.

Moments into the attack, Montcalm had lost control of his army. Authority plummeted down the chain of command as individuals and small groups made their own decisions about whether to go right or left, speed up or slow down, stick together or break apart.

And to stop and fire.

About 130 yards from the British lines, the French stopped and started shooting their muskets.

Casualties were low [from this fire], explained the anonymous author of An Accurate and Authentic Journal of the Siege of Quebec, “owing to the enemy’s firing at too great a distance for their balls were almost spent before they reached our men; several of our people having received contusions on parts where the blow must have been mortal, had they reserved their fire a little longer.

As MacLeod details — and as veteran soldiers of the time must surely have known — muskets are short-range weapons, most effective at 40 yards or closer. But the French, disorganized and heedless of commands, stopped to open fire.

“A murderous instrument”

Wolfe situated his six British battalions, set in two or three ranks, across the 1,000 yards of the battlefield. They didn’t form a continuous line but were separated by 40-yard intervals, and they “gave the impression of fragile vulnerability.” They weren’t.

This fragility was more apparent than real. A European battalion was a murderous instrument. However thin and disconnected the line might be, a linear formation allowed a disciplined army to bring every available musket to bear and deliver a series of devastating volleys.

When the French resumed their charge, they got between 30 and 40 yards from the British soldiers and came to a halt.

And, according to a British chaplain, the two groups of soldiers stood “looking at one another for 2 or 3 minutes, the one desirous the other would give first fire.” That’s because, after that first volley, the other side would have the advantage while the shooters reloaded.

“An intensely personal act”

Finally, the French fired, and the firefight was on. Two groups of men, standing tall and shooting at each other across open ground. MacLeod writes:

Killing at this range was an intensely personal act. Soldiers could see their enemies fall and hear them scream as their shots struck home, feel the blood of wounded comrades splatter across their faces, and choke on acrid clouds of black-powder smoke….

Simultaneously aspiring killers and potential victims, soldiers on the plains faced death at every second….

Only their shirts, vests, and coats…protected soldiers that morning.

MacLeod quotes four soldiers who reported their wounds. Here’s one:

“I was hit by two musket balls, the first tore the thumb off my right hand, the second pierced my right thigh.”

World history

In Northern Armageddon, MacLeod brings to every aspect of the battle as well as the events that led up to and away from it this sort of attention to human detail and vibrant anecdotes.

He notes in his final chapters how important this battle was for world history. It removed French Canada as a threat to the American colonies, thereby freeing the colonies of the need for British protection. Thus, opening the way for the move to independence.

Also, the campaign against Quebec employed a great many American colonists who later were able to use their military experience in the colonial war against the British overlords.

Patrick T. Reardon

4.18.23

NOTE: You can find my 2018 review of this book here.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.