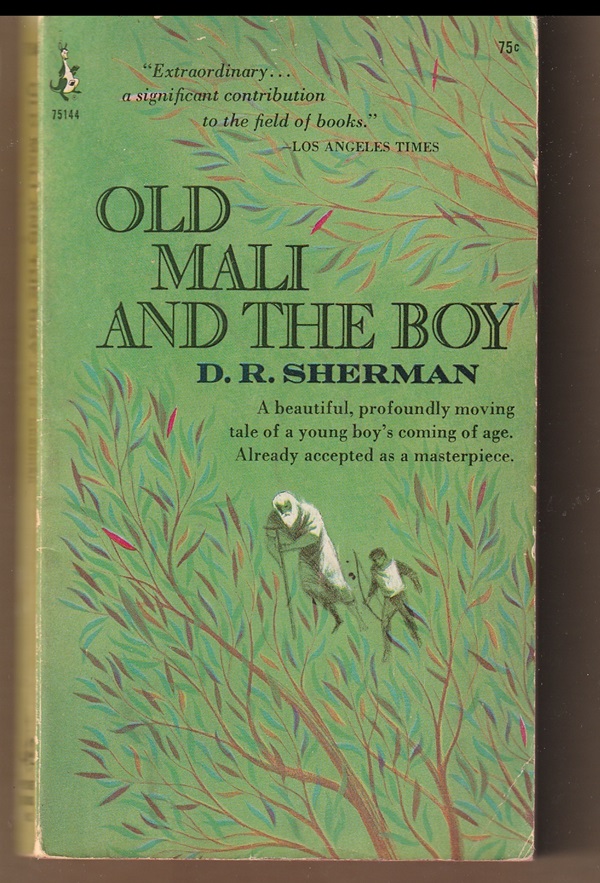

D.R. Sherman’s Old Mali and the Boy, published in 1964, is a complex and poignant fable about love, set in northern India in the first half of the twentieth century.

It centers on a fatherless 12-year-old British boy and an aged son-less Indian gardener. The boy’s name is Jeffrey, but, except for one mention, he is always called simply the boy. The gardener’s name is never given. The boy calls him Mali as if it were his name. It comes from a Sanskrit word and means gardener.

It might be said that this is a tale about the self-sacrifice of love — about all that Mali does to nurture, support and save the boy.

He gives the boy stories, and he gives the boy his cherished bow. For the bow, Mali teaches the boy how to make arrows. And, then after six days of pleading, Mali agrees to take the boy on a three-day trip to hunt deer.

“On the third day, I will return him,” he tells the boy’s mother.

But, after a day and a half of travel, they do not find deer, and, on their way back, danger and tragedy strike. The lives of the boy and the old man are threatened. Through pain and fear and exhaustion, the old man gets the boy back home to his mother in the promised three days — but at the greatest cost.

So, yes, self-sacrifice is part of the story, but this is a much bigger tale.

A love

A love

It is an account of a love.

The love that the boy and Mali share doesn’t fit the usual formulas. They are not related. They are of different cultures, of different colors. The boy is a member of the pampered, dominant (but tiny) English community. Mali is one of the hundreds of millions of Indians who, despite their numbers, are subservient to the English.

Indeed, at this historical moment before the independence of India in 1947, many of the British on the subcontinent looked down on the native people as second-class humans, treating them with disdain and arrogance.

The boy, though, is something of an outsider himself, the only day student at the boarding school where his mother is the kindergarten teacher. His father is dead.

Perhaps Mali, too, is an outsider among his people inasmuch as he works for and gets along with the boy’s mother.

And before he started on the long walk home [after teaching the boy how to make arrows] the memsahib would probably give him some bread and meat.

Aye, he thought, she was a good woman, not like so many of the sahibs and memsahibs he had worked for.

“Not a servant”

Across the great social and psychic distances that separate them, Mali and the boy connect.

When the boy tells Mali about being caned on his butt by the headmaster for disciplinary reasons, he asks the old man not to tell his mother.

To him Mali was not a servant, a menial inferior, and therefore someone who had no right to communicate such matters to his mother. He was an old man whom he liked and loved.

Early in the short book, Mali tells the story of how, many years earlier, he tried to help a bear caught in a trap and suffered a lashed and broken leg. It was, he relates, a long, long journey home, using forked sticks as crutches.

The boy nodded, but still he did not look at the old man. In his mind he was seeing Mali — not the boy he had been, but the man he was now, for he could picture him no other way — limping his way through the steep forests, the forks of the rough crutches under his arm, the broken leg jogging limply beside the wood.

And then in a while the picture changed, and it wasn’t Mali any more, but himself, and he tried to imagine what his mother would say as he came limping up to the door.

“Worship and reverence”

On their journey out to find deer to hunt, they stop after the first day to make beds of branches of a cryptomeria, a conifer.

“Who taught you all these things that you know?”

“I learned in the way you are learning,” the old man said. “By watching and listening to others. It is the only way to learn.”

“You must always let me watch you, Mali,” the boy said quickly and earnestly. “So that I can learn all the things you know about. Will you Mali?”

It touched the old man near the heart, the worship and reverence he saw on the young face. He did not fight the pride and pain which filled him suddenly. He surrendered to it, clutching it to him with a raw passion, savouring the sweet hurting of it all.”

The pain Mali felt was for the son he never had and for the woman he loved as a young man who died of fever before they could marry.

A moral woven through the tale

In Old Mali and the Boy, Sherman’s language is simple and evocative. There is a subtle rhythm to the sentences and paragraphs, an almost biblical cadence.

It is a fable, but not the sort that hinges on the final twist to reveal a moral.

Sherman’s moral, if you want to call it that, is woven throughout the tale, and it is that love connects.

Love connects across age and social standing and culture and expectations.

Mali and the boy each sacrifice. Each gives of himself for the other. More important, each cares for the other, deeply, openly, with full vulnerability.

There are dire twists to the plot of Old Mali and the Boy, but those are secondary to the love of the two characters from the beginning of the novel to its end.

Patrick T. Reardon

8.6.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.