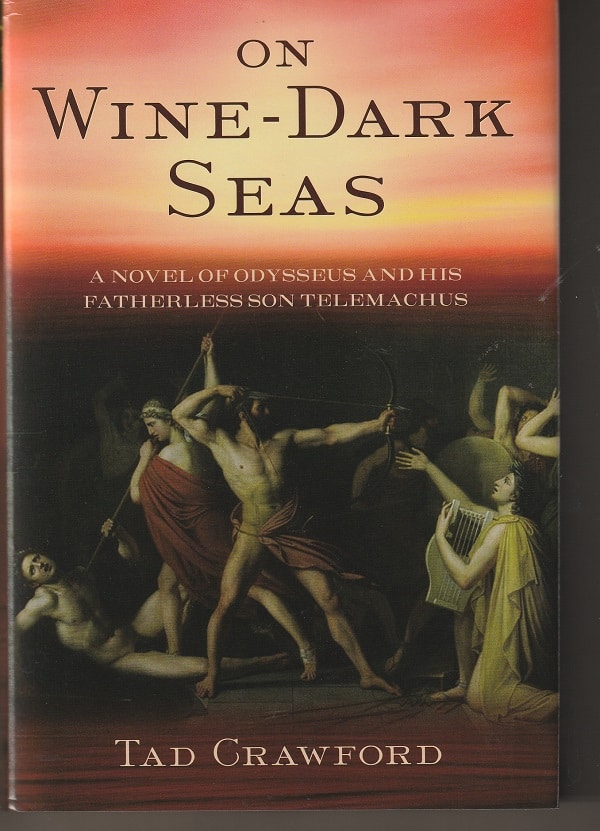

Odysseus’s episode inside the cave of the cyclops Polyphemos plays an outsize role in Tad Crawford’s On Wine-Dark Seas: A Novel of Odysseus and His Fatherless Son Telemachus.

Telemachus, the narrator of this novel, is telling his story of life with and without his father. His audience is the bard Phemios who was an eyewitness to and a survivor of the bloodshed and violent death that Odysseus wreaked, with the help of Telemachus and two loyal workers, on the 100-plus suitors as well as their slave-girl lovers upon his return to Ithaca.

Despite the subtitle, Telemachus was never technically “fatherless.” But he grew up without Odysseus for the first 20 years of life, and then, upon his father’s return, he found himself unsure of how to interact with this man who was and remained for all intents and purposes a stranger. Indeed, at one point, Telemachus reports:

Embracing Odysseus, I wept that this man to whom I clung could never give me all I wanted. In my pain, I felt I would always be Nobody’s son.”

Of course, in that cave episode, Odysseus told Polyphemos that his name was Nobody. The cyclops, the son Poseidon and Thoosa in Greek mythology, had discovered the hero of Troy and his men in his lair, and he was eating those men, one after the other, like small snacks, promising Nobody that he’d eat him last.

When the relatives of those who had gone with Odysseus to Troy came to Odysseus to learn what had happened to their sons and fathers, he told them — in great detail. For instance, the family of Eurybates heard this:

According to Odysseus, the giant Polyphemos took heavy-shouldered Eurybates in one massive hand and devoured him feetfirst. The herald’s screams echoed from the cavernous mouth until his bloody carcass vanished in a single swallow.

“Puny Nobody”

Odysseus blamed his wanderings after Troy on the anger of Poseidon over his blinding of Polyphemos in that cave. So, after his massacre of the suitors and the slave-girls, he followed the instructions of the spirit of the blind prophet Tiresias to make an elaborate sacrifice of oxen and goats to the sea god to lift the divine anger.

In his prayer to the sea god, however, Odysseus is anything but placatory:

“Poseidon, take this wine from a holy grove of Apollo. As it sings in your gullet, remember I, puny Nobody, fed wine like this to your child Polyphemos. He slept like a baby until we Ithacans drilled out the jelly of his eye. Fathomless, blue-maned monster, where were you when that eye sizzled and your giant cried for his daddy?…

“If prophesy is true, I’ll live a long and peaceful life despite your cruelty. So I curse you, Poseidon, as you cursed me.”

Fathers and sons

On Wide-Dark Seas imagines the life of Odysseus after Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, employing as source material the tiny scraps and sketchy summaries of six other epics that, in ancient times, made up the Trojan Cycle.

It’s not a simple task. The fragmentary nature of those six epics give only glimpses into their stories, and those stories are often contradictory. To include as much as possible and yet keep his novel coherent, Crawford opts for a variety of storytelling strategies, including dreams that depict alternative life paths.

Tying the novel’s disparate parts together are its many father-and-son duos.

At the center are Odysseus and Telemachus as well as Odysseus and his father Laertes. Then, of course, Poseidon and Polyphemos. And then all those fathers from Ithaca and other Ionian islands whose sons were slain in the killing spree of the returning hero.

Hated, shunned and threatened with stoning

Not that the residents of Ithaca or those other islands see Odysseus as a hero.

The fathers and families of the murdered sons, in Crawford’s telling of the story, are out for Odysseus’s blood despite his glory at Troy. They have to be bought off with all of the treasure he has brought back to Ithaca.

Then, Odysseus, even though he curses Poseidon, slaughters hundreds of his oxen and goats to the ocean deity and leaves himself, his wife Penelope and Telemachus nearly destitute, forced for the rest of their lives to live hand-to-mouth.

And not only destitute but also shunned by other Ithacans. For one thing, the returning warrior’s stories about his ten years after Troy — the stories in Homer’s Odyssey — seem like fairy tales to his neighbors. And, then, there are those tales he provides of the suffering and deaths of their menfolk.

And, then, there is the effort, led by the fathers of the slain Ithacan suitors, to drag Odysseus before the assembly to face the threat of being stoned to death for leveling his curses against Poseidon and potentially bringing disaster to Ithaca.

The testimony of Aigyptos

At the assembly, after a series of speeches against Odysseus, Lord Aigyptos, the leader of the gathering, breaks tradition by speaking rather than just presiding. He talks of his two dead sons, one of whom was Antiphos who accompanied the Ithacan leader to Troy and on the homeward journey:

“Odysseus told me that Polyphemos — a Cyclops, a giant — devoured my son. How I raged against Odysseus and cursed him for a liar. Why couldn’t Odysseus have returned after my death, after the deaths of all of us who fathered the sons given to Troy? What gratitude I would have felt to learn Antiphos lived as a pirate or even a slave….

“When Odysseus said this monster devoured my son last, I wished the gods had dulled the monster’s appetite.”

And then Aigyptos speaks of his other son, Eurynomos, one of the suitors for Penelope slaughtered by Odysseus, Telemachus and their two servants:

“When Eurynomos spent day after day in the hall of Odysseus, I lightly imagined the master long dead. To myself I rebuked his widow for mourning more than seven years.”

Yet, the grieving father does not lash out at Odysseus. He recognizes that the fathers of Ithaca “sent our sons to Troy, not Odysseus. We let our sons plunder another man’s home.” And, so, he says:

“I thank Odysseus for leading my boy Antiphos to Troy. If any man could have saved Antiphos and brought him home, that man is Odysseus.

“As for my other son, Eurynomos, I thank Odysseus for letting him die like a man. Who will ever say a weakling killed him, when his slayer was Odysseus, plunderer of cities?”

Whose son?

Near the end of On Wine-Dark Seas, the rhythm of stories dealing with fathers and sons takes a sharp, surprising turn.

Odysseus is recounting his efforts to reach Ithaca and Poseidon’s efforts to block him when, seemingly, he is visited by a sudden thought:

“Sometimes I think Polyphemos wasn’t Poseidon’s son at all. If he had a divine father, why did he lose his eye to me? No, I think Polyphemos had a heathen giant for a father and that I was the son of Poseidon.”

This statement astonishes Telemachus. What about Laertes? Oh, of course, Laertes is his father, too, Odysseus says. But he goes on:

“Poseidon punished me like a father. His strength showed me my own limits, the outer boundary separating man and god. On that night when Laertes and Anticlea conceived me, who can say the spirit of Poseidon was absent?”

It’s a striking way for Crawford to bring his story of Odysseus and Telemachus to its end.

Is this from one of the lost books of the Trojan Cycle? Or is this Crawford’s elaboration on, extrapolation from, those fragmentary stories?

It doesn’t matter.

On Wine-Dark Seas works well as a sensitive imagining of the post-Odyssey Odysseus and of all those in his circuit. It wrestles with the mystery of the Trojan hero and avoids easy answers.

In its relentless examination of the relationship of fathers and sons, it is deeply resonant of the human experience.

Patrick T. Reardon

3.16.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.