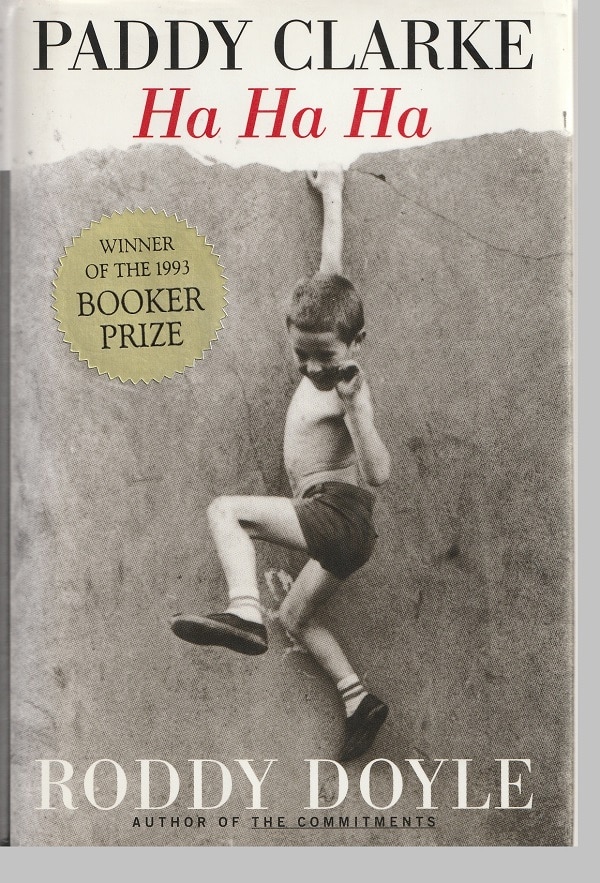

Paddy Clarke is a nine-year-old, lower middle-class, small-town Irish boy who turns ten somewhere during the course of Roddy Doyle’s hilarious, revelatory and achingly tender 1993 novel Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha.

The oldest of four children, he is the book’s narrator, describing life as he lives it and as he finds it from a perspective that is, at once, childish and knowing. He is innocent and violent in the way of children, but also has a child’s awareness of important and incompletely understood events happening at the edges.

He is constantly trying to figure things out, trying to understand how things fit together, trying to plumb all the mysterious knowledge that adults clearly have.

“The crust”

For instance, near the middle of the novel, Paddy, out of the blue, starts talking about scabs, revealing his fascination with the stuff that happens to his body:

I was good at waiting for the scab to be ready. I never rushed. I waited until I was sure it was hollow, sure that the crust had lifted off my knee. It came off neat and tidy and there was no blood underneath, just a red mark; that was the knee being fixed. Scabs were made by things in your blood called corpuscles. There were thirty-five billion corpuscles in your blood. They made the scabs to stop you from bleeding to death.

Clearly, here, as in other places in the novel, Paddy’s comments are colored by something he’s read and retained, at least for the moment. He’s very familiar with how his body forms and then drops away scabs, and he’s wedded that to bits of knowledge he’s picked up about blood.

He likes the clarity of it all — the scab lifting off the knee at just the right time, the knowledge of the exact number of corpuscles in the blood — and the clear reason for it: “to stop you from bleeding to death.”

“The only one who knew”

Suddenly, though, on the next page, again out of the blue, Paddy is facing something that’s filled with ambiguity, uncertainty and anxiety. His brother Francis, called Sinbad, a year or two younger, is usually his ally, accomplice and acolyte, but not in trying to understand and deal with this threat:

Sinbad didn’t notice the way I did. There had to be shouts and screams and big gaps between them before he knew anything. When it was quiet it was fine; that was the way he thought. He wouldn’t agree with me, even when I got him on the ground.

I was alone, the only one who knew. I knew better than they did. They were in it; all I could do was watch. I paid more attention than they did, because they kept saying the same things over and over.

—I do not.

—You do.

—I do not.

—You do, I’m afraid

Ma and Da

Anyone who knows children knows that they experience and feel and know much more than adults give them credit for.

Paddy hadn’t gone looking for problems between his Ma and his Da, but he’s felt the emotional vibes of tension between them and then started to recognize evidence of that tension. (This is, in a way, what childhood is all about, getting an idea of how life works and then gathering evidence to test that idea.)

And, for Paddy, nothing could be more threatening for him as a nine- and ten-year-old, as the oldest of four children, as a child who knows the comfort and consolation of home, than trouble between the two people responsible for that home and for that family, two people he loves deeply, his Ma and his Da.

As the tension escalates to the novel’s climax, Paddy is ever more frantic to find a way to block a future he can’t even consider.

I watched. I listened. I stayed in. I guarded her.

Everything he does is focused on the here and now, on keeping the quiet fighting from occurring, often through magical thinking — if he stays up all night in his bed, if he stands watch in this way, they won’t squabble, and life will be safe.

He smiled at me.

I loved him. He was my da. It didn’t make sense. She was my ma.

Neither parent is aware — no one is — of what Paddy is doing to keep them from fighting. He really is alone.

“Swayed like snow”

The plaintive nature of Paddy’s confusion, fear and feeling of duty to solve a problem beyond his imagining is heightened by the earlier indications of his deep innocence and enjoyment at the unfolding of his life.

Consider, for instance, the nostalgia of the nine-year-old for a time and a place several years earlier:

Under the table was a fort. With the six chairs tucked under it there was still plenty of room; it was better that way, more secret. I’d sit in there for hours. This was the good table in the living room, the one that never got used, except at Christmas. I didn’t have to bend my head. The roof of the table was just above me. I liked it like that. It made me concentrate on the floor and feet. I saw things. Balls of fluff, held together and made round by hair, floated on the lino….

The sun was full of dust, huge chunks of it. It made me want to stop breathing. But I loved watching it. It swayed like snow.

That was then. Now, though, he is bigger.

I couldn’t do it any more. I could get under the table but my head pressed the top when I sat straight and I couldn’t sit still; it hurt, my legs ached. I was afraid I’d be caught. I tried it a few times but it was stupid.

The burden of growing older.

“So they could graze”

For a long time, Paddy and his friends ignored bicycles, preferring instead to run through their neighborhood and the construction site of new homes being built along the edge of Barrytown. Then, older, now nine and ten, the crowd of boys found bikes a wonderful addition to their haunting of the half-built homes and roads.

We charged through on our bikes. Bikes became important, our horses. We galloped through the garage yards and made it to the other side. I tied a rope to the handlebars and hitched my bike to a pole whenever I got off it. We parked our bikes on verges so they could graze.

The rope got caught between the spokes of the front wheel; I went over the handlebars, straight over. It was over before I knew. The bike was on top of me. I was alone. I was okay. I wasn’t even cut.

“Til you go up?”

Paddy had a sister Angela who was stillborn and immediately baptized “otherwise she’d have ended up in Limbo,” instead of heaven.

When his mother told him this, he wanted to be sure “the water hit her before she died.” Yes, his mother said.

I wondered how she managed, a not-even-an-hour-old baby, by herself.

—Grandma Clarke looks after her, said my ma.

—Til you go up?

—Yes.

As a parent, I’ve been in the middle of conversations like that, such as when my eight-year-old son told me that he was going to take my art books when I died, but he hoped it wouldn’t be for a long time, maybe, 17 years. (That was 27 years ago.)

“Only horses and zebras and small monkeys”

It’s clear that, for Paddy, it’s comforting to think that, in heaven, his mother will be there to take care of him and his sister Angela. Much better than Limbo:

Limbo was for babies that hadn’t been baptized and pets. It was nice, like heaven, only God wasn’t there. Jesus visited there sometimes, and Mary his mother as well. They had a caravan there. Cats and dogs and babies and guinea pigs and goldfish. Animals that weren’t pets didn’t go anywhere. They just rotted and mixed in with the soil and made it better. They didn’t have souls. Pets did. There were no animals in heaven, only horses and zebras and small monkeys.

Such is the innocent logic of the boy Paddy, taking things that have been said to him and that he’s read and that he’s reasoned out and synthesized them into an understanding of this aspect of living.

He is wide-eyed and artless and oh-so-yearning to figure out life. And his reasoning about Limbo will do him fine now, and he won’t need to change it much as he grows older.

Some parts of life, however, don’t bend so easily to a child’s reasoning, as Paddy, to his sorrow, learns.

Patrick T. Reardon

5.31.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.