I’m tempted to say that Lisa Russ Spaar’s novel Paradise Close has a fairy-tale quality to it, but I’m afraid that would give the wrong idea.

That might suggest that there is a lightness about it, a simplicity, even a childishness. But Paradise Close is nothing like that.

This is a complex novel of psychic wounds suffered that continue throbbing down the years, never fully scarring over. It is a story of deep emotional connections found and then lost. A story of living through and then living after great trauma. Of love made and then not made.

A book of just 219 pages, the novel spans more than a century of life, from 1914 to 2017, during which multiple characters approach, dance around and touch one another lightly or deeply. And everyone ends up alone, for at least long periods if not into old age.

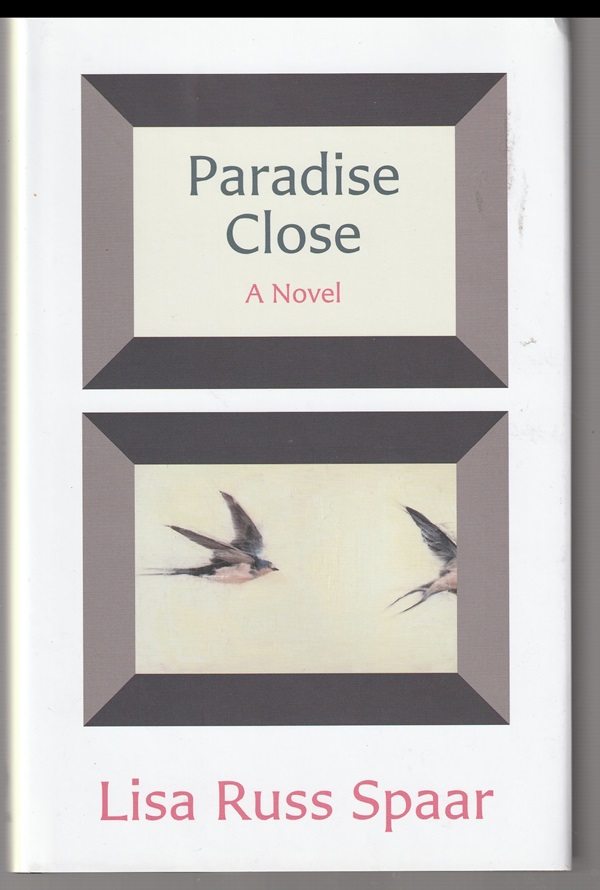

Spaar is a poet, the author of ten collections over the past four decades, and Paradise Close, her debut novel, has the intensity, conciseness and observational richness of poetry. Originally published in hardcover in 2022 by the New York-based Persea Books, the novel is now released as a paperback.

“Her own frail vest of bone”

It is a story told in three parts. The first, set in 1970-71, centers on Marlise Schade, a 14-year-old anorectic orphan who must leave her treatment at a psychiatric hospital in Philadelphia because her trust fund money has run out. Maruice, her godfather, affectionate but distracted by his own life, sends her to live at the virtually abandoned Paradise Close, her great-great grandparents’ homestead in rural Bucks County, PA.

It was a place of former prosperity — corn fields, orchards, a vineyard — where Marlise had once been carried in the arms by her mother, Beatrice Schade, the mythic Bea, with a family hybrid peach named for her, the Beatrice Cross, though Marlise could not remember her long-dead mother, except as she surfaced in one photograph Marlise possessed of her, with its white border and date stamp, 1955, skeptical eyes flickering in heart-shaped face, a parasol balanced over her shoulder as she squinted into sunlight.

During this section, Marlise recalls events and interactions at the Institute, particularly with her one friend Silas Newman, a 20-year-old emotionally troubled artist who will soon be too old for the facility.

Alone in the house, Marlise nibbles on Saltines and feeds nearly all the other food delivered for her to barn cats and birds.

Sometimes in the dark, in bed, inside one of the nightgowns that was in the box of clothes that had come from Maurice soon after she’d arrived, cast-offs, she guessed, from some step-daughter or another, she’d hear geese lowering over the rooftop toward the river, their migratory thonking coming from right up inside her own frail vest of bone.

She is floating through her days, starving and near death, when an intruder breaks in.

“Deep, fruit-perfumed kisses”

The second section tells of Trey “Tee” Hardy, a red-headed assistant professor at a Virginia university who, in 2000, has just published a book of poetry. He needs cover art, and, on the recommendation of a colleague, he meets Emma Miles, a professor in the university’s Studio Art department who is married and has a teenage daughter.

The second section tells of Trey “Tee” Hardy, a red-headed assistant professor at a Virginia university who, in 2000, has just published a book of poetry. He needs cover art, and, on the recommendation of a colleague, he meets Emma Miles, a professor in the university’s Studio Art department who is married and has a teenage daughter.

They fall in love — or, at least, into an intensely sensuous affair. They can’t get enough of each other. On one occasion, they drive out to orchards with natural springs bathhouses two hours away.

They held hands, something they could rarely do out in the open air. She sang a nursery song, apples, peaches, pears. Feeling better, Tee sang also, off-key, about a bird that flew, tangled up in blue. He had a terrible voice, but Em loved it. Deep, fruit-perfumed kisses, mixed with the egg-tainted bathwater, her hair and collar still wet with it. A breast in his hand. Nipple stippling. Fragments of Spanish spoken somewhere, faint laughing, a pure clang now and then, an engine rumbling, deep within the bladed, diesel-scented, darkening and fragrant aisles.

Then, they have a fight. And never see each other again — at least, in part, because of circumstances.

The Hole

One of those circumstances is that, in 2001, Tee, mournful over his loss of Em and preoccupied with her memory, decides to leave the university and teaching and move into a mansion in Bath County, VA, newly available after the death of a great-uncle’s wife. It was known as Handel Hall. As a visiting teen, Tee renamed it Handel Hell. Now, he called it The Hole.

From a high spot nearby, he looks down upon his new home, even if he occupies only a small part of it:

From there he could see, by late October, if he squinted, the six chimneys of the old house, his house, inherited fifteen years ago from a great uncle, and which, despite its immensity, was partially hidden even in winter by swells and thick mesh of treetops, enisled by its own vast acreage amidst miles of state and national forests in an area known for lightning strikes, chalky screes of iron ore, and hot springs.

It is now 2016, and Tee is past sixty, going about the routines of his melancholy life. And then — like a lightning strike — he discovers in one of the many unused areas of the mansion an intruder, a younger woman who can’t remember her name or how she got there.

Fairy tale quality

The first section of Paradise Close is 112 pages; the second, 88. They lead up to the must shorter third section, 29 pages. It is this final section that, as I suggested earlier, gives the novel its fairy tale aspect.

There is a fairy tale quality to the parallels in the stories of Marlise and Tee that are apparent by this point — their solitary existences on old family properties, their burdens of psychic damage, their loss of parents in childhood, their aimlessness, their intruders. And there is a fairy tale quality to the action as it unfolds in this section.

It is now January, 2017, and an art exhibit in Manhattan brings together, like multiple arrows in flight, the novel’s century-worth of characters, of hidden love and loss, of moving close and pulling away, of aching loneliness and flickers of connection.

Closed loop

The playing out of this third section echoes the tight, closed loop of a fairy tale — the witch pushed into her own oven, the sleeping beauty kissed, the clicking of ruby slippers at the end of The Wizard of Oz.

And, like many a fairy tale, this is a story that suggests a moral. Or, better put, since this is a novel that reads like a poem, a story that suggests many possible morals. Such as:

The intruder may be deadly or open a door to life.

Or:

You can never know all the connections of all the people who brought you to this moment.

Or:

We are all lost souls, and, sometimes, we find each other, if even for a moment.

Patrick T. Reardon

3.18.25

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.