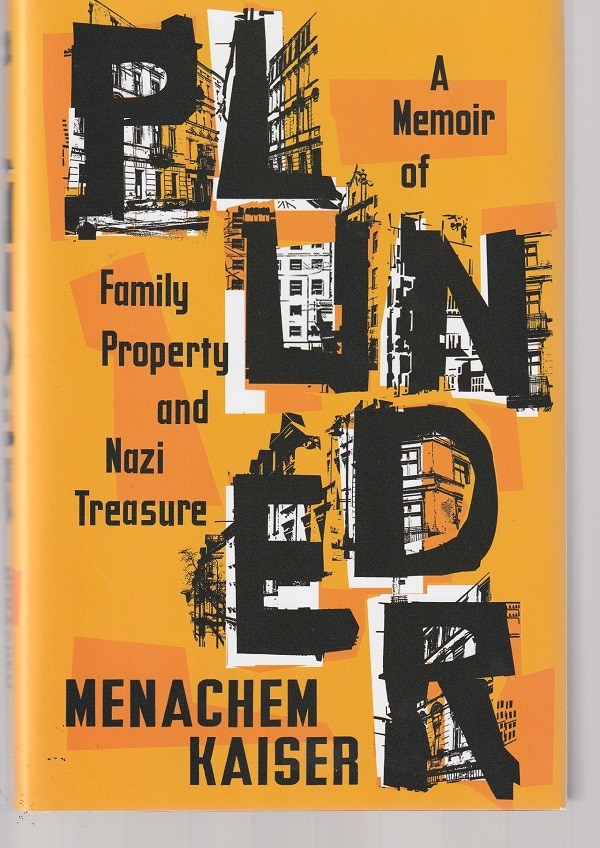

The cover of Menachem Kaiser’s book features several line drawings of large apartment buildings on an orange and white background that gives the appearance of having been Scotch-taped in place. Each apartment building image is covered for the most part by what looks like a large black graffitied letter.

The letters combine to form the word: PLUNDER.

The full title of Kaiser’s book is Plunder: A Memoir of Family Property and Nazi Treasure, and, with that name and its cover, the book appears to be the latest installment in what has become a genre of memoirs in which modern-day descendants of Jews murdered in the Holocaust return to Europe and attempt to regain their family’s stolen and/or lost possessions.

Indeed, at one point, Kaiser underlines the savage reality of what it means that there have been so many such memoirs:

“Anyone who spends time with the genre will quickly apprehend the ancillary tragedy that it’s a genre: these mind-shatteringly horrific stories are common enough and familiar enough that they can feel ordinary, even banal, sometimes even cliched.”

In general, such memoirs are presented as a righteous crusade in the name of fairness, virtue and justice. Not only did the Nazis/Germans/Poles/whoever kill my family members, but they stole/destroyed/gave away/whatever our family’s art/money/factory/building/something of value, and I’m here to get it back, even if — especially if — you won’t help me recover it.

The descendant is depicted as being clearly on the side of goodness, and anyone who was involved in taking the valuable stuff away from the family or is involved in keeping it away from the family is, to one extent or another, seen as being on the side of evil. They plundered our valuables, and now I’m here to get them back.

Except, in Kaiser’s book, he writes of himself as a plunderer.

“The unknowable space”

A few pages from the end of his book, Kaiser, a Brooklyn writer, explains that he doesn’t trust the genre in which Plunder fits, a genre that is “too certain, too sure-footed,” one in which “meaning is too quickly and too definitively established,” a type of book that makes “no acknowledgement of the abyss, the void, the unknowable space between your story and your grandparents’ story.”

These memoirs, he writes, are framed as missions, but that’s false “or at least not the truest truth.” And he goes on:

“ ‘Mission’ suggests the possibility of completion, redemption, catharsis, but there can be no completion, redemption, catharsis, because our stories are not extensions of our grandparents’ stories, are not sequels.

“We do not continue their stories; we act upon them. We consecrate, and we plunder.”

“Questions that cannot be formed”

By this point in his book, Kaiser has already made it clear that his own effort to recover an apartment building in Poland — one that his grandfather owned when he was forced into the concentration camps where all but one other member of his family died — was exceedingly complex from an array of personal, moral, social and historical perspectives.

His Zaidy (Yiddish for grandfather) survived the camps, settled eventually in Canada and died in April, 1977. Kaiser never met him. He was born eight years after his grandfather’s death and given his grandfather’s name, Meir Menachem Kaiser.

Early on in Plunder, Kaiser examines his motives for undertaking this effort. Part of it, the start, was happenstance. He was in Poland on a Fulbright scholarship.

In a way, his endeavor and that of any relative of a Holocaust victim is like any family member’s genealogical searches, except “a thousand times more intense, given that most of the branches of the family tree terminate with horrific abruptness.” And, in another way, it is a means of moving a step closer to “an ineffable tragedy.”

The idea of a righteous crusade by a descendant to recover family property seems simple, but, as Kaiser observes and relates, it is much more convoluted:

“What are these descendants searching for? Sometimes it’s straightforward. Sometimes the questions are answered with a visit to an archive, or a conversation with an elderly local. But I think they are often searching for answers to questions they don’t know how to ask, questions that cannot be formed.”

Wrong-headed and fuzzy-headed

The great value of Plunder: A Memoir of Family Property and Nazi Treasure is not that Kaiser unravels horrifying, inspiring, angering poignant secrets. He doesn’t.

Indeed, as he clearly spells out, Kaiser goes about his task in a clumsy, time-wasting, frustrating manner. He is wrong-headed at times and fuzzy-headed at others — as he clearly spells out.

Indeed, his bumbling extends the process, and, as his book comes to an end, Kaiser has to acknowledge that the question of whether his family will be able to recover the building it once owned is still up in the air, still floating in the legalist fog of the Polish court system.

But his book’s great value is that Kaiser goes through this process — and brings readers along with him — with an openness to the moral complexities of everything that he is doing and of everything that was done to his family from the moment that his ancestors boarded their trains to the camps.

In this search, Kaiser doesn’t find much to help him connect with his grandfather — but he does find a great deal about a semi-famous camp survivor Abraham Kaiser, a distant relative of his zaidy.

He doesn’t connect with his grandfather, but he does connect in an odd, at times uncomfortable way with Polish treasure seekers who haunt a massive and unexplained system of Nazi tunnels and who use Abraham Kaiser’s Holocaust memoir as a roadmap in their search for anything of value, but particularly the long-rumored Nazi Golden Train.

“Site of death, not treasure”

The great value of Plunder is that Kaiser is open — and forces his readers to be open — to the confused lines of rationale exhibited by those treasure seekers and by others he met and, even more, by himself. At the height of the Gold Train fever, Kaiser writes, a deputy prime minister

“sought to remind everyone what this site actually was: the train, the gold, whether or not it existed, was incidental; much more important was the fact that thousands of slave laborers had died here. This was a site of death, not treasure, and we should act accordingly.”

Here and elsewhere in his book, Kaiser is not finger-wagging at those Polish treasure hunters, nor at those people who moved into the buildings left vacant by the deportation of his grandfather and other Jews.

He doesn’t wag his finger because, in his own acknowledged way, Kaiser is also a treasure hunter, seeking a monetary treasure, to be sure, but also a familial one and — he is a writer after all — a professional one.

At many points, Kaiser is honest enough in his story to recognize his complex ambitions. Indeed, after his father raises questions about his aims, Kaiser considers his motives and writes:

“The reclamation was an assertion of a relationship with my grandfather, and of a relationship of a particular sort, and the fact of the matter is — so my father was saying — that this was not the sort of relationship my grandfather would have cared about, or at least not the kind he would have prioritized.

“And my grandfather was — via my father, the rightful or at least most qualified spokesman — responding, The building? Who cares about the building? That’s not what I want us to share, that’s not what I wanted you to inherit.”

A complex book

Plunder is a book for a popular audience, but Kaiser goes out of his way to make his story as complex as possible — because it is complex.

He goes out of his way to make sure that the reader understands that a story of trying to recover valuables lost in the Holocaust can’t be simple. He doesn’t rasp away the rough edges, he doesn’t try to tell a story of good guys and bad guys.

Of course, everyone involved in carrying out the Holocaust was morally stained and everyone killed by that process was innocent. But Kaiser and those he encounters in Poland and elsewhere around the world exist six, seven decades after the fact.

He is honest enough as a reporter, as a memoirist, as a human being to recognize the complexity of the events and emotions that he stirs up in his quest to recover an apartment building.

The Holocaust

Plunder is a book, not so much about the Holocaust, but about families and memory and vulnerability.

And, of course, it is also absolutely about the Holocaust. Nothing Kaiser does in his book or writes in his book is without the recognition of the Holocaust.

But, in a real way, nothing in the present everyday world of 2021, anywhere on the globe, occurs without the knowledge, either conscious or suppressed, of the Holocaust and its tragedy.

In the face of the inhumanity of the Nazis, Kaiser has written a deeply humane book.

Yes, he is plundering his family history. Even more, though, through his honesty and openness, he is, as he writes, consecrating it.

Patrick T. Reardon

8.12.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.