Throughout the 20th century, postcards were an easy, cheap way to keep in touch. Often, they were sent home by tourists, but postcards were also sent to memorialize or comment on or proclaim events closer to home.

You could make a postcard of any photo, and an astonishing variety of subject were treated this way. Perhaps the darkest was the use of postcards to record lynchings, the subject of the chilling book, Without Santuary, published in 2000.

In that context, it’s not surprising that it’s possible to trace the course of the waves of the Russian Revolution through postcards, as the Bodleian Library does here with nearly 90 cards, all but two from the huge collection of John Fraser.

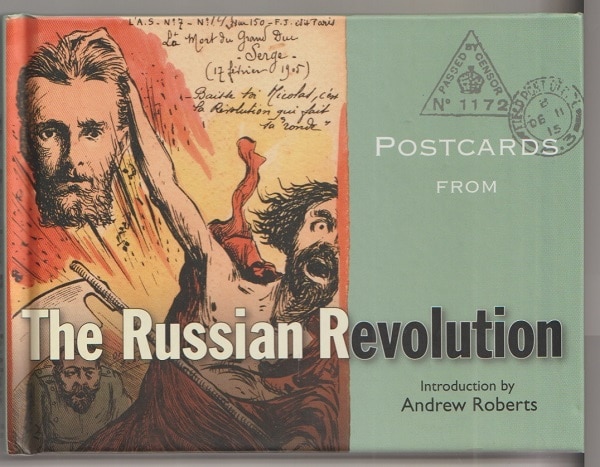

In an introduction to Postcards from the Russian Revolution, published in 2008, Andrew Roberts writes:

“Maxim Gorky, Leo Tolstoy, Catherine Breshkovsky (‘the mother of the Revolution’), Alexander Kerensky, Lenin in close up, a jolly, pipe-smoking Stalin, and many other identifiable individuals are all depicted, either in photographic or drawing or cartoon form, but so is an elderly, white-beared man who turns out to be Almighty God himself, as satirized by the anti-religious Soviet propaganda machine.

“The sheer comprehensiveness of the collection, and lack of political bias in the choice of what was amassed, makes this remarkable and attractive volume a fascinating visual snapshot of political events in Russia from the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5 right up to the Bolshevik victory in the Civil War seventeen years later.”

Here are some of the images

The Tsar

Tsar Nicholas II has always seemed a tragic figure to me, a guy who had no aptitude or training for his job, too timid and small-minded, a guy who only got the job because his father was assassinated, a guy in way over his head and, through personality and upbringing, totally unable to acknowledge that.

The “priest”

George Gapon (in the light robe) was a Russian Orthodox priest and working-class organizer — and, most important, a secret police agent. His treachery discovered, he was hung a year after this photo was taken.

The demonstration

The resolve, good feeling and even joy of the outbreak of revolutionary activity in 1905 is palpable here, in a photo taken only a short time before some 1,000 marchers were killed or wounded when soldiers fired on the crowd.

The assassination

In a French cartoon postcard, the figure of Revolution holds up the head of the assassinated Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, the young uncle of Nicholas II who cowers in the background.

The mastermind

It’s an avuncular-looking Lenin who is seen here chatting with British writer H.G. Wells who later wrote: “Lenin has a quick-changing brownish face with a lively smile and a habit (due perhaps to some defect in focusing) of screwing up one eye as he pauses in his talk; he is not very like the photographs you see of him because he is one of those people whose change of expression is more important than their features.”

The children

A few years after this photo was taken, these children of Nicholas II, along with their parents and some servants, were shot and bayoneted to death in a basement.

Patrick T. Reardon

2.5.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.