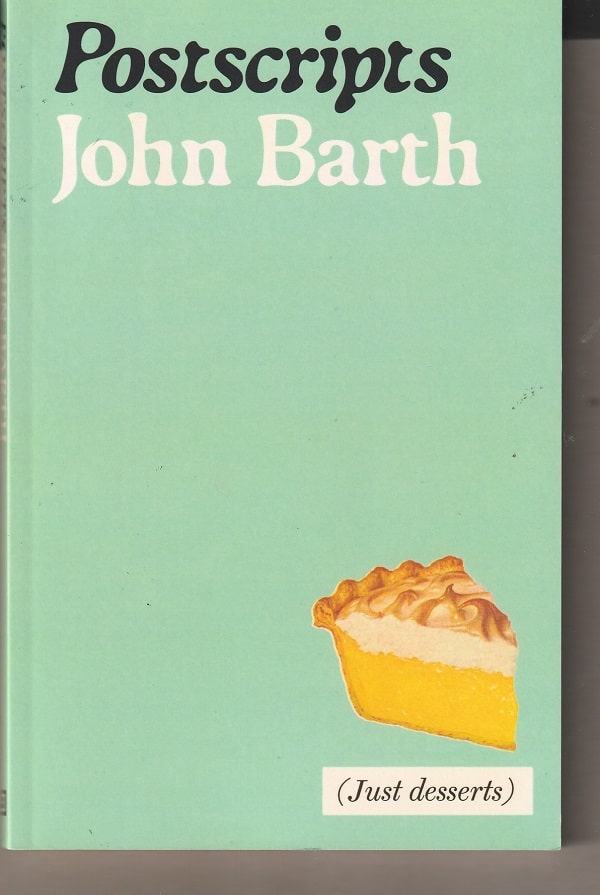

The words aren’t there on the cover of Postscripts (or Just Desserts), but they jumped out at me when I turned to the title page:

“Some Final Scribblings.”

That’s not something you want to see acknowledged by a writer whose work you’ve enjoyed deeply through many books.

Say it ain’t so, John Barth!

I came to Barth late — blame a lack of adventurousness on my part — but, since I found him, I have enjoyed his wildly inventive, clever, sprightly, playful, interconnected meta-fictions — from Chimera (1972) to Every Third Thought: A Novel in Five Seasons (2011), from The Sot-Weed Factor (1960) to The Last Voyage of Somebody the Sailor (1991), from The Development: Nine Stories (2008) to Coming Soon!!!: A Narrative (2001).

But, really, what did I expect?

Barth was a huge presence in American literature in the 1960s and 1970s — indeed, throughout the second half of the 20th century. Now it’s the 21st, and I didn’t even know about Postscripts, published last year, until I stumbled over an obscure mention of it on the internet, and, well, Barth, born in 1930, will turn 93 on May 27.

It’s melancholic for me, this book and what it means.

It doesn’t seem to bother Barth, though.

Wit, lightness, friskiness

What he’s assembled in a book of 143 pages are 49 very short pretty much non-fiction pieces, many of them in the nature of observations. In a foreword, he writes:

Now in my nineties, having perpetuated eleven novels, two novella-triads, four short-story series and three essay collections, I find myself attracted to the even shorter form of mostly one-page jeux d’esprits…

Jeux d’esprit is a French term for a witty comment or composition, and that’s what Barth is after here — wit, lightness, friskiness even. He notes at many places throughout the book that his muse has always been one with a grin, not a grimace.

Although many of these deal with or touch on his advanced age and approaching death, his tone is far from gloomy. Barth seems to find life, as he always has, endlessly fascinating, and he obviously still enjoys word play and joyful mind games.

“Meta-crap”

For the most part, he’s not up to his old meta-fictional tricks. One exception is the story that he titles “This Is Not A Story,” just as Rene Magritte produced a large painting of a pipe above the French words “This is not a pipe.”

Barth mentions that painting in the seven-page story about a story that just can’t get started. Along the line, the writer attempting to make a story happen is identified as Manfred Zilch, and the false starts begin to add up, and Zilch finds that he has managed,

against all odds, to have thus far perpetrated three pages of yadayadayada while waiting for our dormant-if-not-deceased Muse to get off her sweet lazy butt and

KNOCK KNOCK!

Who’s there?

NOBODY

Nobody who?

Nobody in her/his mind will put up with this meta-crap much longer….

Steering the course

Barth uses a four-page piece titled “Navigation-Stars” to talk about the four works of literature that he has used to steer his literary course:

- Homer’s Odyssey, the travels of Odysseus and the resourcefulness of Penelope, holding down the home front and awaiting his return.

- The Arabian Nights, anonymously written, featuring Scheherazade as a storyteller for 1,001 nights to save her skin from the mad (as in angry and as in insane) king who is bedding her.

- Don Quixote by Cervantes, in part because of Barth’s participation in a Great Books class at Johns Hopkins University and his particular classroom insight into the book that resulted in “a moment especially felicitous for a callow undergraduate like my then self.”

- And, of course, Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn — “the raffish, mischievous, juvenile, and very American equivalent of Odysseus and Quixote….While Huck is not half-crazy like Quixote, not dealing with monsters, gods, and demons like Odysseus, and not yarning to save the show like Scheherazade and Homer’s Penelope, he epitomizes adolescent rebelliousness in its American flavor.”

Wordsmithery

As I mentioned, Barth deals in several places in these pieces with his advanced age and nearing death.

In the final piece, titled “Out of the Cradle,” he takes a wandering stroll through such subjects as his youthful tendency to rock himself to sleep, rocking chairs, other sorts of rocking, the Hoagy Carmichael song “Old Rockin’ Chair’s Got Me,” teenage masturbation, the source of the term “off one’s rocker,” his tendency to rock in his desk chair while working, and, finally, on the last page, his preoccupation with his eventual death.

This, he writes, is a preoccupation “that, while often sharpening the pleasures of a many-blessinged life, sometimes dulls their edge and threatens to pre-empt my professional imagination.”

It is, he writes, “quite chilling” to consider death “or, worse, one’s own or one’s mate’s approaching infirmity, dependency, bereavement, and the rest.”

There it is.

How then come to terms with The End, except — small comfort, but doubtless better than none — by fashioning sentences, paragraphs, pages out of its inexorable approach, while not for a moment imagining that such worthsmithery will delay by even 1.5 seconds the thing’s arrival?

I rock and consider, in pensive (though not wordless) vain…

With this book, Barth has continued his wordsmithery. For whatever it’s worth. Which seems to be not nothing.

Patrick T. Reardon

3.30.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.