If you pick up a copy of Daniel G. Brinton’s Rig Veda Americanus: Sacred Songs of the Ancient Mexicans, originally published in 1890 and now again in print from Northfield-based Amika Press, you’ll find a hymn, addressed to the Mother of the Gods, that includes the verse: “Hail to the goddess who shines in the thorn bush like a bright butterfly.”

“O, friends,” begins one to another deity, “the quetzal bird sings, it sings its song at midnight to Cinteotl [the God of Maize]./The god will surely hear my song by night, he will hear my song as the day begins to break.” Meanwhile, there’s a hymn to the goddess of the child-bed that ends with birth: “Come along and cry out, cry out, cry out, you little jewel, cry out.”

Brinton was one of those gadabout 19th-century amateurs who got his fingers into a lot of stuff, often with interesting and important results. A surgeon, historian, archeologist and ethnologist, he spent his final years as an advocate for anarchy.

His Rig Veda Americanus was the first English translation of 20 Aztec hymns, and this review has two stories to tell:

- first, how the book provides piquant and, at times, gruesome insights into the religious faith of those Mesoamerican people, six centuries after their culture was snuffed out by invading Spaniards, and

- second, how the small Amika Press came to republish the book.

Let’s deal with the publishing story first, and that means talking to Sarah Koz, one of the three owners of Amika, a publisher that has produced some fifty titles since 2000, most of them works of fiction.

“A Passion for World Myths and Religions”

It all began, she tells me in a phone interview, about 15 years ago when she was studying at International Academy of Design and Technology in the Loop and was given an assignment by her teacher Nathan Matteson to take an out-of-copyright book and design it into a printable book.

She chose Brinton’s obscure work, already more than a century old, because “I really had a passion for world myths and religions.”

It was a complex task, Koz explains, since Brinton presented his English translation of each of the 20 hymns in the book with three parallel, related items — his commentary, the original Nahuatl language version and a gloss or annotation in that language, apparently by Rev. Bernadino de Sahagun who gathered the hymns in the first place.

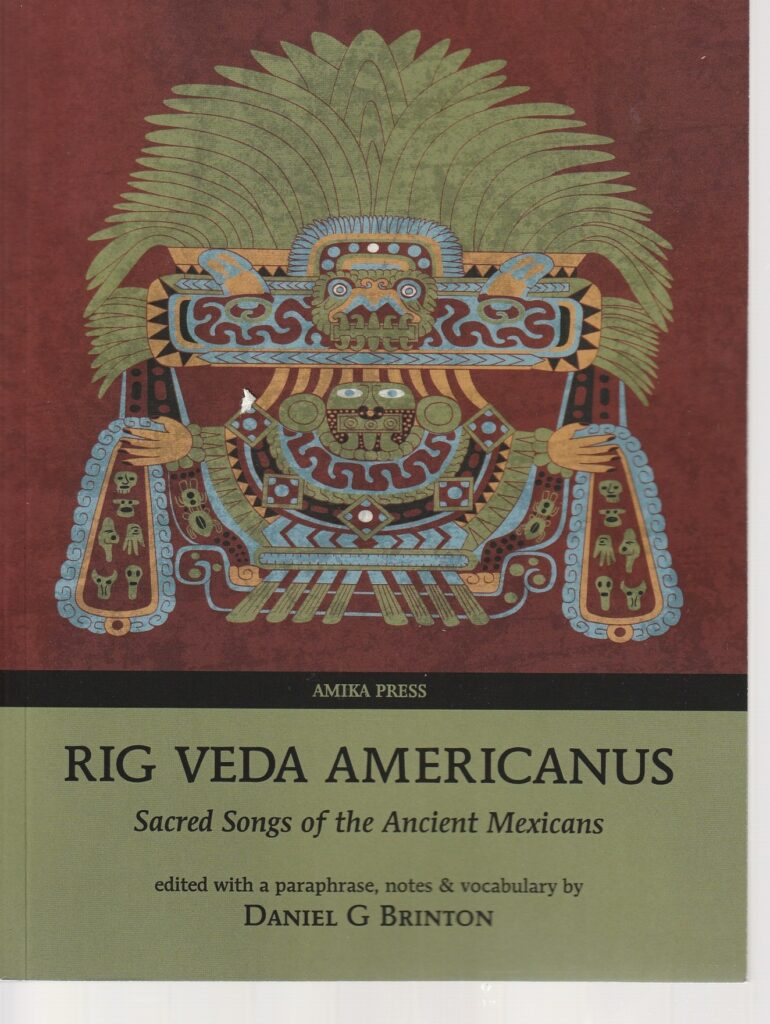

To make this four-part package readable, Koz laid out each hymn on a two-page spread. She also designed a layout for Brinton’s glossary of terms and for his index as well as recreating four images of Aztec art, one of which depicts the Great Goddess of Teotihuacan and is featured on the cover.

After completing the assignment, she set her Brinton design aside until recently when she noticed how an entire subgenre has developed in which specialized publishers take out-of-copyright works and just pour the text into an ebook format. That may be fine for a digital copy, but it can make for an incredibly messy print-on-demand book for anyone who orders a paperback version.

Koz got the idea of using the Brinton book design to produce for Amika a royalty-free book that would be readable when printed as a paperback. Not that she expected a lot of readers when it was published on February 22.

“I didn’t expect any sales ever,” she acknowledges. But, to her surprise, she says, “I’ve made $1.53 from four sales already!”

So, what began as a lark has actually resulted in a handful of readers, and now Koz is thinking she’ll produce a series of redesigned out-of-copyright books, such as perhaps a novel by a now-forgotten 19th century English woman or maybe a book about Chicago from the past.

“Painted with Serpents’ Blood”

Those subjects are more likely to attract readers than Brinton’s Rig Veda Americanus. Indeed, how many modern readers will recognize that the title is a reference to the Rig Veda, an ancient canonical Hindu text that is a collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns?

Nonetheless, if you have an interest in poetry or in comparative religion, you’re likely to find Rig Veda Americanus fascinating on several levels.

Consider, for instance, the start of this hymn to Cihuacoatl, also called Quilaztli, the mythical mother of the human race:

“Quilaztli, plumed with eagle feathers, with the crest of eagles, painted with serpents’ blood, comes with her hoe, beating her drum for Colhuacan [the place of the old men]./She alone, who is our flesh, goddess of the fields and shrubs, is strong to support us.”

Cihuacoatl is the mother of fertility — but also of violence as some later verses make clear:

“Our mother is as twelve eagles, goddess of drum-beating, filling the fields of tzioac & maguey like our lord Mixcoatl [god of hunting and of the tornado]./She is our mother, a goddess of war, our mother, a goddess of war, an example and a companion from the home of our ancestors.”

There are references in a couple of the hymns to Aztec ballplaying, such as the final verse in “Hymn to Mixcoatl” which reads: “In the ball ground I sang well and strong, like the quetzal bird; I answered back to the god.”

Ballplaying was part of the religious culture, as was ritual violence and murder. “The War Song of the Huitznahuac” includes the verse:

“Ho! Youths for the Huitznahuac, arrayed in feathers, these are my captives, I deliver them up, I deliver them up, I deliver them up, arrayed in feathers, my captives.”

That seems harmless enough until you read Brinton’s commentary. It apparently was, he writes, the custom at a particular annual festival to take “the slaves who were to be sacrificed,” divide them into two teams and set one against the other “to slaughter each other until the arrival of the god Paynal put an end to the combat.”

“Serpents and Frogs”

This new publication of Rig Veda Americanus by Amika Press is a kind of historic artifact. Brinton’s translation of the 20 hymns represented what was known and understood about them in 1890. Undoubtedly, there has been more research and insight developed over the past century into the Aztec culture and probably better, more rigorous translations of the hymns. Koz made no attempt to fit Brinton’s work into the present state of scholarship. It is simply what it is.

Still, for the non-scholar, it’s likely to be enough, especially at the cost of $4.44.

Any window into another culture, particularly one from so many hundreds of years ago, can broaden the reader’s perspective. In Brinton’s book, the reader comes to know, in a modest way, a religion that involves playing ball and setting slaves to slaughter each other. And not only that.

In his commentary, Brinton notes that “The Hymn sung every Eight Years when They Fasted on Bread & Water” was for a festival at which there was one exception to the fasting. He quotes from Rev. Sahagun that “certain natives called Mazateca swallowed living serpents and frogs, and received garments as a recompense for their daring.”

What sort of garment? Even more, what sort of serpent? Rig Veda Americanus is a glimpse into quite a different culture.

Patrick T. Reardon

5.24.22

This review originally appeared at Third Coast Review on 4.14.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.