There’s a tendency to think of great painters such as Michelangelo and Rembrandt as geniuses who worked alone. Of course, they’d have a lot of support staff, if only to pay the bills or sweep up or run errands, and maybe assistants to do some of the more routine brushwork.

However, for two centuries, a counter-trend took place in the Low Countries, a region that encompassed present-day Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. Between 1500 and 1700, painters not only created works on their own but also, routinely, collaborated with a second master to fashion paintings that took advantage of the individual skills of the two artists.

The greatest of these collaborations was between Jan Brueghel the Elder and Peter Paul Rubens, “the most eminent painters in Antwerp” at the turn of the 17th century and a team that produced about two dozen works together, according to Rubens & Brueghel: A Working Friendship.

The book by Anne Woollett and Ariane van Suchtelen is the catalogue for an exhibition in 2006-7, mounted by the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and the Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis in The Hague.

More than two-thirds of its pages deal with the commentary on and presentation of 13 canvases jointly produced by the two men. In addition, there are eight paintings by Brueghel with another artist, three Rubens collaborations with Frans Snyders, one work by Rubens alone and four by Brueghel alone.

Two artistic traditions

As Woollett explains in an opening essay, Brueghel and Rubens represented two artistic traditions in the city:

Brueghel’s exceptionally meticulous and graphic brushwork deftly described multitudes of people seen from a high vantage and details of the natural world, while Rubens captured emotion and corporeal energy with vigorous brushwork in large-scale history paintings.

Such cooperative work between Brueghel and Rubens, nine years younger, was common in their artistic milieu.

Collaboration, the process by which two or more artists work together to produce a single work of art, is virtually synonymous with painting in the Low Countries before 1700….Frequently, the principal artist would plan the composition, executing the most important areas himself, and engage the services of a second painter for the figures or details.

Rubens and Brueghel were close friends, and, Woollett writes, their collaboration seems to have been the result of a desire to work together as is evident from “the delight and wit that pervade many of their paintings.”

In the past, the assumption has often been that, in the collaboration, Rubens played the lead role. However, Woollett notes that “it is clear from the works assembled here that Brueghel played the largest part in developing and executing their joint works, particularly during the second half of the 1610s when their working method had become more streamlined and included Rubens’s workshop.”

Brueghel taking the lead

Of the 13 works by the two men, the catalogue indicates that Brueghel was the main artist in nine of them. For instance, in The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man, Brueghel “laid down the composition by means of an underdrawing, using only a few lines to sketch in the contours of the landscape on the primed panel,” writes Ariane van Suchtelen in an essay on the painting.

Using this outline, Rubens began to paint, rendering “the play of light on Adam and Eve’s skin with subtle nuances of his palette.” Then, it was back to Brueghel:

When Rubens had finished his part, Brueghel took over and applied a green tone as a basis for the landscape. Then he painted the sky….He went on the paint the larger animals and then worked up the landscape surrounding them…

Brueghel integrated Rubens’s contribution into the composition by applying small retouches along the contours.

Brueghel painted such paradise scenes in several works, creating, Van Suchtelen writes, “painted encyclopedias of the animal kingdom” with his depictions of the species “based primarily on empirical knowledge.”

Rubens taking the lead

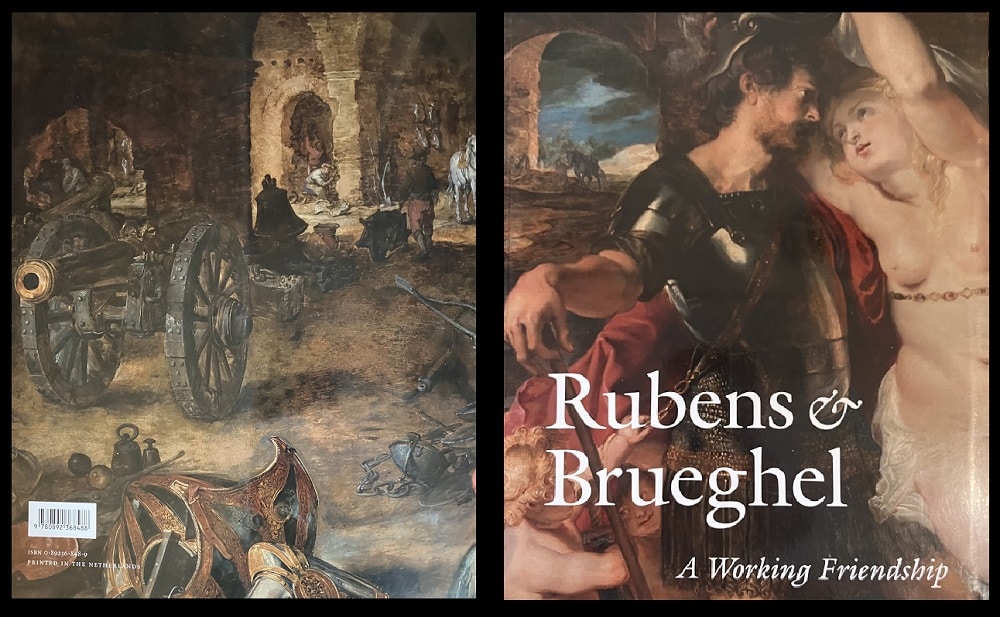

Rubens was a team leader in The Return from War: Mars Disarmed by Venus, a work that was unknown to art historians before it was acquired in 2000 by the Getty. The work is displayed across the back and front covers of the book:

Here, the initial work was done by Brueghel who, according to Woollett’s essay on the art, “painted the cavernous interior and the foreground accoutrements.” But Rubens had his own ideas, the main one being to change the subject from a Venus in Vulcan’s Forge to a depiction of Venus seducing Mars, an allegory for peace.

It’s a sign of the friendship and working relationship of the two men is that, when Rubens got the canvas from his collaborator, he proceeded to paint over some of the work that had already been done, taking more of the surface for the two figures he now envisioned. And Brueghel didn’t squawk.

Rubens’s substantial alteration was in keeping with his independent contribution to the commission. More than simply adjusting the subject with the addition of standing figures, Rubens eliminated extraneous attributes that did not support the new theme. As we shall see, there is every reason to believe that Rubens discussed the transformation of the theme with Brueghel, whose later contributions served to enhance it.

Back and forth with the canvas

In presenting the political allegory, the two men added “an additional, sensual, layer of meaning.” Woollett writes:

There are delightful visual puns, such as the phallic cannons to the left of Mars and the loose bridles, added by Brueghel after Rubens’s revision, hanging next to the aggressively seductive goddess….

While this painting’s exceptional tactility adds an additional dimension to the allusion to the sense of touch, it also clearly demonstrates how Brueghel’s graphic brushwork complements Rubens’s broad handling, creating a setting the envelopes the figures and enables them to inhabit space.

These two paintings are the richest and most beautiful of the book’s 13 cooperative works from Brueghel and Rubens. But great riches can be found in all of the other works presented here that the two men did together as well as the 16 works they did with other collaborators or on their own.

Rubens & Brueghel: A Working Friendship is a lush and luscious gathering of strikingly attractive works of art by two of the great artists in history.

Patrick T. Reardon

5.2.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.