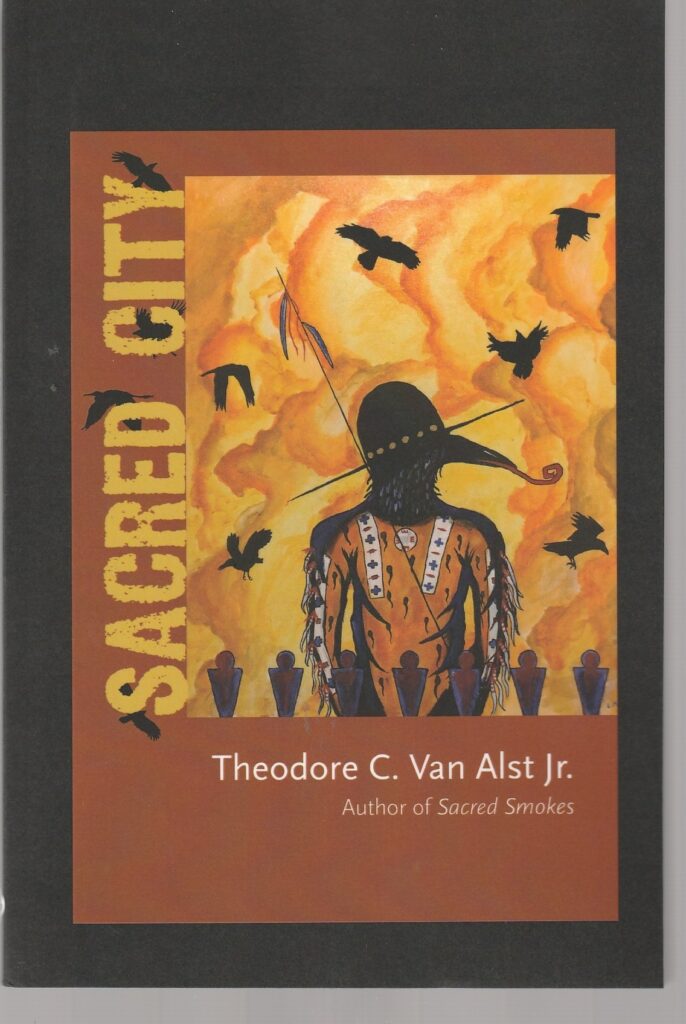

The Teddy in Theodore C. Van Alst Jr.’s new short story collection Sacred City has a way of telling a tale that starts here and ends up there after a lot of twists and turns.

Such as in a paragraph, midway through his story “Lamb,” when he is explaining how his family, descendants of converted Indians, would attend St. Margaret Mary’s Catholic Church, up near Touhy and Western.

He starts the paragraph off by mentioning that, one time, as a nine-year-old, he was given some coins to put in the collection plate. He wanted to keep them, but didn’t because he knew his seven-year-old brother would turn him in. And then he relates:

We would walk up Seeley Ave. to get to the church, and on the way there was a picture of a white-white Jesus in the window of this old lady’s apartment. It was the white Jesus with the eyes, the ones that look like a deer’s but really are more like a judgy assistant principal’s.

The brother is terrified of Jesus “with his judgy fingers.” Teddy is terrified of their father — and the tendency of his brother, “a goodie-goodie little shit,” to rat him out. Which leads to the end of the paragraph:

We went to run away once, and as I was walking out the door, blanket, food, spot picked out, he went in to tell my ma goodbye. Jesus.

“White-white Jesus”

The full “Lamb” story is the same way, a lot of this direction and that direction. It starts with Teddy, also called Midget, hanging out with JD and some other teenage friends at the apartment of Jimmy1’s family. (Teddy also has friends Jimmy2 and Jimmy3.) He decides he wants to tell them a story:

Teddy and JD are in the living room of an apartment, looking for stuff to steal. Well, that, and JD has made himself a bologna and cheese sandwich. “I forgot he ate a sandwich every time he did a burglary. Ya poor-ass bastard. Some of these white boys are hardcore.”

And, now, as he always does during a burglary, JD is taking a shit.

It’s at this point that Teddy goes on that tangent about going to church and walking past the “white-white Jesus.”

And, then, well, the burglary goes bad in eighteen different ways, but not before Teddy tries to visualize the life of the people who live in the apartment, “a sad couple,” who, he is sure, would benefit if he set fire to all of their stuff and burn out their crappy memories and “make them make some new ones, remember life is short and that’s why it’s so precious.” But he decides against it, figuring they’d just go out and buy the same old crappy stuff.

And, then, well, a lot happens.

An electric nervy-ness

Sacred City, with its 23 stories, is a lot like “Lamb” and a lot like that church paragraph.

As a storyteller, Van Alst has a restless vigorous intelligence. His refusal to tell a story in a straight line is rooted in a hyper-awareness of the interconnections of things, of people, of actions and accidents, of past and present and what will come.

There’s a jumpiness to his prose, an electric nervy-ness. It crackles with hard-and-fast realities, with facts, set amid a baseline of context, of history, of geography, very local geography.

Such as the Rogers Park of the 1980s where Teddy is a teenager, chilling at Pottawattomie Park on Rogers Avenue, taking part with the Simon City Royals in dustups with other neighborhood gangs that usually don’t involve guns, shoplifting in the Zayre’s (today the Chicago Math and Science Academy) and dining on a tuna melt deluxe at the Gold Coin Coffee Shop on the southwest corner of Howard and Clark (now a small park).

Anyone familiar with Rogers Park will recognize the physical landscape in which Teddy operates, even though some of the landmarks of his generation have disappeared.

Anyone who was an American teenager will recognize a lot of what Teddy relates, particularly the clannishness of adolescents. His teen years, though, are set within a hardscrabble world in which a band of whites, blacks and Indians are raising themselves, for better or worse, enjoying the attractions of petty crime, enjoying their comradeship, and not really expecting to live past 30.

“An indescribable horizon”

I have no idea how closely the Teddy of these fictional stories resembles Van Alst, a professor and chair of Indigenous Native Studies at Portland State University. Certainly, the feel of 1980s Rogers Park and the roving teenage boys on its streets seems on target enough to signal someone who was there then. And, in some of the stories, it’s an older Teddy, now an academic, who is maneuvering in the larger world but still with roots on those teenage streets.

Indeed, in “Forever Young,” Teddy, attending an academic conference in Minneapolis, finds himself in a bar, sitting across from another academic, but one from the Gaylords, a rival gang back in their teen years in Chicago.

Me and this Ojibway GL watch each other, meaning we watch each other’s eyes. That’s where the violence happens, hints at its own oncoming escalation and arrival.

Teddy knows his Indian history, and, in four of the stories, he has a visit from Indian leaders of the past — Simon Pokagon, Techumseh, Tenskwatawa (also known as The Prophet) and Black Hawk. In each case, he gives a tour of modern-day Chicago, to the surprise and, usually, chagrin of the leaders.

In “Black Hawk Goes to the Zoo,” the Sauk leader hates the cages at the Lincoln Park Zoo — and he does something about them. The result is freedom, freedom, freedom, and the story ends:

Hundreds of bird eyes roll up to an indescribable horizon, pour through now-open space, take flight in a riot of flapping wings.

He smiles.

Look at this, grandson.

“Its own sense of time”

Teddy seems surprised that he’s survived a couple decades past 30. Maybe he made it because he was the sort of thief who would also steal a paperback novel during a burglary or read a Tolkien book before a fistfight.

Or maybe it’s because Teddy, for all the grittiness of his growing up, has an eye for beauty, such as this description of a moment during the toddling flight of an infant down a church aisle:

It’s one of those moments that takes on its own sense of time, slo-mos down to heartbeat speed. Light streams through the stained-glass windows and down onto the red carpet, the light pouring through the lurid stigmata even redder on the floor, yellow and blue jewels of roman helmets and rugged crosses diffuse on the faces of the parishioners and [the infant].

Not nihilistic

Hardscrabble childhood and street gang membership often lend themselves to a nihilistic view of life. Not for Teddy, though, as this collection of stories from Van Alst shows. After all, in the midst of a burglary, Teddy is thinking: “Life is short and that’s why it’s so precious.” And there’s the one night when he and his father talked.

Teddy’s father was a drunk who was so rowdy that, even though he was more than 60, he still found himself in jail once. “My old man drank himself to death.”

One night, Teddy tells the reader, he and his father drank together, “and he told me things….So much pain. So much that could have been passed down. And wasn’t.”

Teddy has pain in his life, but he is not poisoned by it. Maybe that’s because his drunk father was not just a drunk. In that one conversation:

He told me one thing I remember clear as a bell.

He told me

“I was a bad father. I’m sorry.”

It is a moment of grace and generosity and atonement. And of beauty.

Patrick T. Reardon

12.16.21

This review was originally published at Third Coast Review on 10.31.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.