At any number of points in Saint Francis of Assisi, the book’s writers make the point that the thirteenth-century Italian mystic and friar has been many things to many people over the last eight centuries.

For instance, Gabriele Finaldi, the director of the National Gallery in London, writes:

Francis continues to be an attractive and influential figure today for Christians and non-Christians alike, for pacifists and environmentalists, for those who clamor for social justice, for utopians and revolutionaries, for animal lovers and for those who work for causes of human solidarity.

Andre Vauchez, the author of the highly praised 2012 Francis of Assisi: The Life and Afterlife of a Medieval Saint, writes:

As we have seen, Francis of Assisi was and continues to be interpreted and appropriated in wildly divergent ways, depending on historical circumstances (and agendas). Not all of these have the same legitimacy. That said, we should recognize that his person, like that of Jesus or the Buddha, possesses a strength of contemporary resonance which permits him to have an impact on humanity up to our own time.

Vauchez goes on to end his essay with a quote from G.K. Chesterton’s 1923 biography Saint Francis of Assisi:

“Francis anticipated all that is most liberal and sympathetic in the modern mood; the love of nature; the love of animals; the sense of social compassion; the sense of the spiritual dangers of prosperity and even of property.”

Even more eloquent

Even more eloquent about the myriad perceptions of Francis are the scores of artworks and other images that fill Saint Francis of Assisi — showing Francis preaching to the Sultan and to the birds, taming a wild wolf and wedding Lady Poverty, reaching his arms wide to accept the stigmata of Jesus’s wounds on his own body and to hug the whole of creation, founding the Franciscan religious order and embracing the poorest of the poor.

Even more eloquent about the myriad perceptions of Francis are the scores of artworks and other images that fill Saint Francis of Assisi — showing Francis preaching to the Sultan and to the birds, taming a wild wolf and wedding Lady Poverty, reaching his arms wide to accept the stigmata of Jesus’s wounds on his own body and to hug the whole of creation, founding the Franciscan religious order and embracing the poorest of the poor.

Saint Francis of Assisi is the catalogue for a three-month exhibit at the National Gallery in 2023 in which more than thirty works of art and historical artifacts were on display. It also includes dozens of other paintings, drawings, photographs and even movie posters that were not in the exhibit.

The authors of the book are Finaldi and Joost Joustra, the associate curator of art and religion at the gallery. Vauchez contributed his essay, and providing some catalogue entries were three gallery staff members — Susanna Avery-Quash, Laura Llewellyn and David Sobrino Ralston — as well as two other scholars, Ayla Lepine, an expert on theology and the history of art, and Jennifer Sliwka, a specialist in Italian Renaissance art.

“As a mother would”

Saint Francis of Assisi is a rich resource for scholars of religion, culture and art history. And, for the general reader, it’s a treasury of art that is evocative and arresting. Francis the man who lived nearly eight hundred years ago was not a serene figure, and his story has been stirring things up ever since.

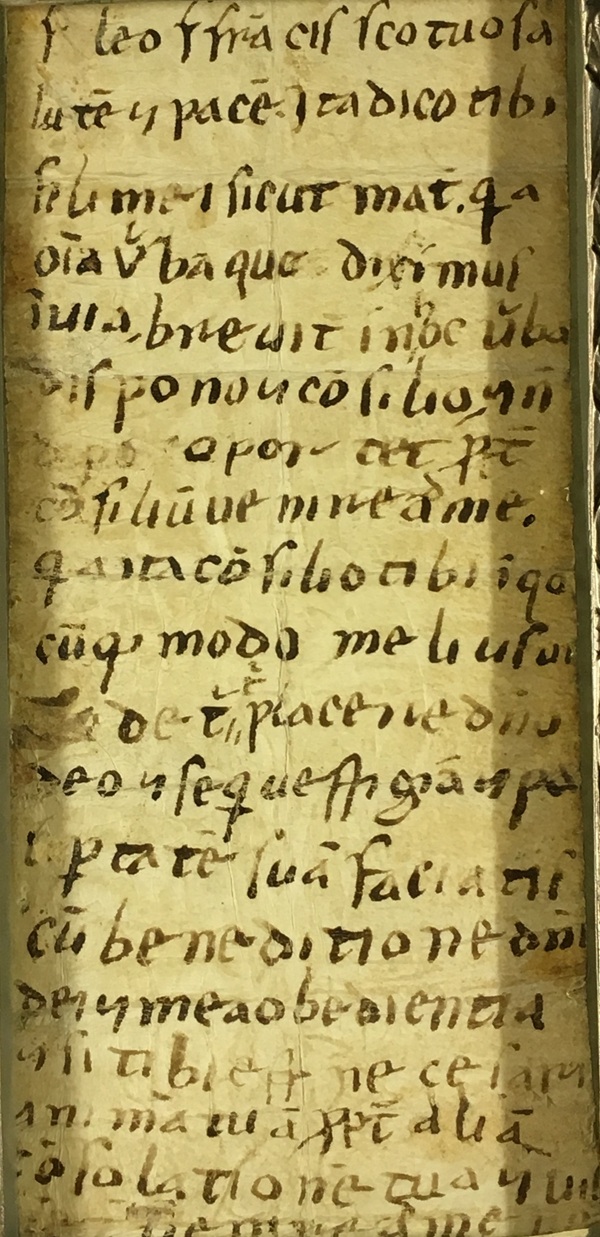

Each reader will respond to this book in a personal way. I was fascinated by two items in the catalogue which were hand-written by Francis. One is a tiny little letter (Catalogue 6) that he wrote to Brother Leo, his companion and confessor, between 1224 and 1226:

Brother Leo, health and peace from Brother Francis! I am speaking, my son, in this way — as a mother would — because I am putting everything we said on the road in this brief message and advice. If afterwards, you need to come to me for counsel, I advise you thus: In whatever way it seems better to you to please the Lord God and to follow His footprint and poverty, do it with the blessing of the Lord God and my obedience. And if you need and want to come to me for the sake of your soul or for some consolation, Leo, come.

Also in the book is a photograph of Francis’s woolen habit and hemp belt (Catalogue 30).

“Intoning the Canticle?”

The famous painting Francis in the Desert by Giovanni Bellini (late 1470s), now in the Frick Collection, was not included in the exhibit but is mentioned often in this book because it influenced many later works.

Francis stands barefoot and looks upward, and the marks of the stigmata can be seen on his hands. This has led some over the years to see this as the moment during which — or right after which — the saint was marked with the wounds by God.

However, another interpretation, writes Finaldi,

suggests that Francis is shown here intoning the Canticle of the Sun, his extraordinary hymn to the beneficence of God for having made the sun, moon and stars, water, fire and “Sister Mother Earth who nourishes and sustains us” as well as all living creatures and even “Our Sister Bodily Death.”

While in the Bellini painting Francis faces the viewer, he faces away in Giovanni Costa’s Brother Francis and Brother Sun (1878-85, Catalogue 17), looking to the east at the rising sun with his arms wide.

In this moment of love and openness, it’s easy to imagine the mystic reciting or singing the Canticle of the Sun.

“Rotund, bearded”

Modern images, while not as overtly reverent, can be just as affectionate, such as Stanley Spencer’s Saint Francis and the Birds (1935, Catalogue 22). Susanna Avery-Quash writes:

Spencer’s evocation of Saint Francis is quirky and memorable. A rotund, bearded elderly man with chin jutting heavenwards and flailing arms, wearing a dressing gown and slippers, leads a gaggle of hens and ducks down a sunny path, past a red-tiled building.

Although the painting sparked loud opposition, Spencer said that “the figure of St. Francis is large and spreading to signify that the teaching of St. Francis spreads far and wide.”

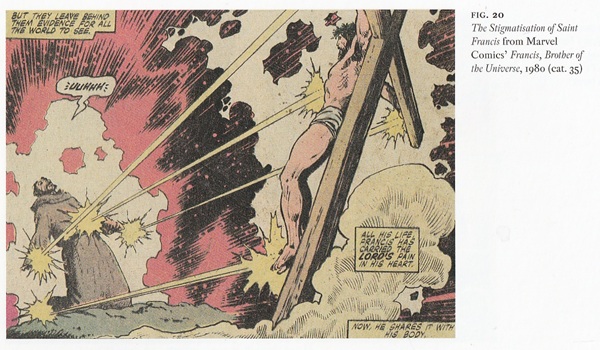

Another modern image envisions Francis as a sort of superhero, albeit one with faith and hope as superpowers — Francis, Brother of the Universe: His Complete Life’s Story, a 1980 Marvel comic (Catalogue 35). The scene of Francis’s stigmata is presented in, well, a Marvel Comics sort of way:

“His mother, his bride, and his lady”

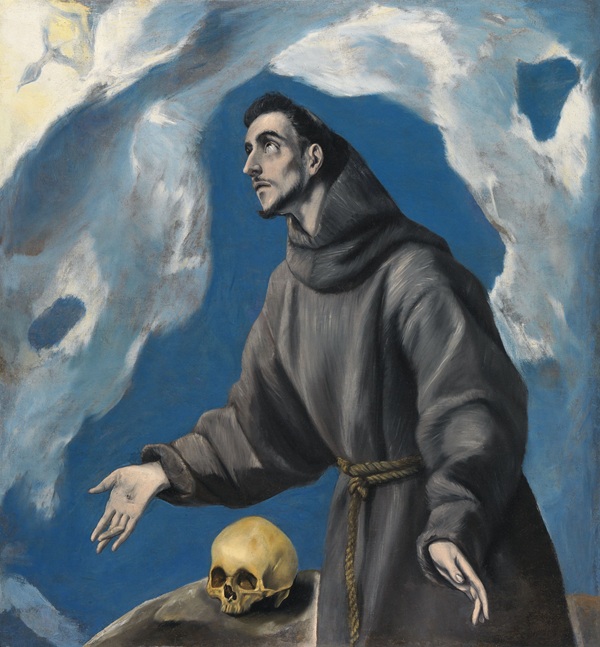

El Greco, who was also criticized by some of his contemporaries for his idiosyncratic style, painted Francis more than ten times, including Saint Francis receiving the Stigmata (1590-5, Catalogue 11). David Sobrino Ralston writes:

In this painting, El Greco has stripped away nearly every incidental detail of the setting in favor of an unremitting focus on Francis’s inner experience, a decision that emphasizes the saint’s asceticism and solitude on Mount La Verna.

A key interpreter of Francis was the fifteenth century Italian artist Sassetta who created Scenes from the Life of Saint Francis in 1437-44 (Catalogue 4).

The National Gallery owns seven of the eight charming and devout scenes which were part of a monumental double-sided altarpiece. One of the most delightful of the scenes is the Mystic Marriage of Saint Francis with Poverty, Chastity and Obedience which is included in the book although it was not in the exhibit. Joostra writes that the scene is based on episodes in two early biographies:

On his way to Siena, Francis encountered three women personifying the three Franciscan vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. It is Poverty who is shown accepting Francis’s ring, “his mother, his bride, and his lady,” in [one biographer’s] words.

What’s wonderful about the scene for me is the elegance of the encounter on the road and then the elegance of the three women floating off to heaven.

Fanciful and reverent

One final image was created as few as fourteen years after Francis’s death in 1226. It’s in the Chronica Maiora II, a bound vellum manuscript that was an attempt at a universal history of the world. While he was expanding the work, Matthew Paris, a Benedictine monk in England, included a marginal drawing of Francis.

Although contemporaries, Paris and Francis lived a thousand miles apart and never met, so Paris’s image of the saint is fanciful. Yet, it’s that fancifulness and clear reverence that makes the drawing so compelling. By the way, those birds have been identified as a heron, a crane and probably a hawk as well as two generic songbirds.

Patrick T. Reardon

4.25.25

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.