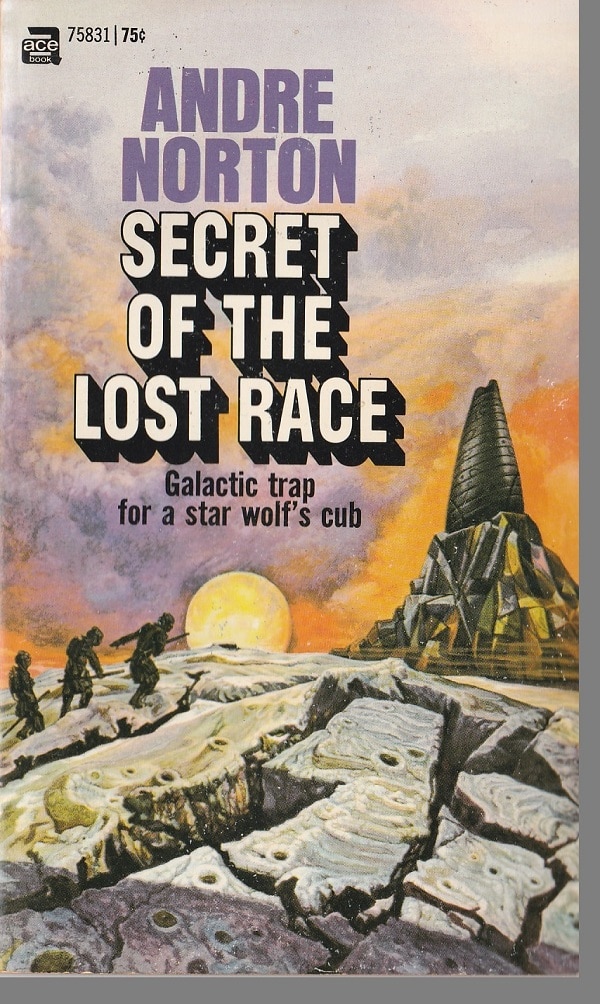

It turns out, in Andre Norton’s 1959 Secret of the Lost Race, that the secret about the survivors of the much earlier civilization is pretty eye-popping, biologically speaking.

But, because it is the twist at the very end of the novel — it comes on page 122 of the 125-page book — it would be unfair of me, to future readers, to disclose the surprise here.

Suffice it to say that it opens up some pretty interesting philosophical questions. And it works within the universe that Norton has created, even if my sense of science, admittedly sketchy, raises questions about its likelihood in the real Cosmos.

“I like puzzles”

Secret of the Lost Race is the story of Joktar, a youthful-looking card dealer in a casino called SunSpot in JetTown, the port of N’Yok, on Terra, run by a savvy operator named Kern.

Fifteen years earlier, Joktar’s mother stumbled into the SunSpot and promptly died. Kern took the “smart brat” in, and now Joktar, adept at maneuvering the JetTown streets, is something of an advisor to the owner as well as a cipher. He’s thought to be 18 but looks even younger.

“Why did you keep me here, Kern?”

“Well, boy, I like puzzles and you’re about the best I’ve ever got my hands on. You grow a little bigger, but slow, and you keep looking like a kid, yet you’ve got a brain that ticks fast and straight and you don’t get smart ideas.”

But, then, Joktar gets shanghaied to work the mines in Fenris, a cold dangerous world with a winter that lasts three-quarters of the year.

Was this happenstance or by design? Throughout the novel, Norton interrupts her narrative to insert secret messages inside various organizations of unclear purpose, dealing with Joktar’s whereabouts and future.

“The sensation of loneliness”

Meanwhile, Norton goes to great lengths to emphasize how alone her character feels. In part, this is because of the unforgiving world he finds himself on. More, though, he feels separate from others and knows that his earliest memories have been blocked through some sort of mind manipulation.

When he is the only survivor of an accident on the road, he must find a way to keep alive: “Now he stood alone, buffeted by the moaning wind.”

Later, after he kills a cat-bear, called a zazaar, and lives through a blanket storm — think blizzard, but much worse — Joktar is searching for shelter.

Underfoot the snow creaked. The eerie stillness was somehow more nerve twisting than the onslaught of the storm. He was one small living thing in that white cup where only a poisonous flag of steam waved. And the quiet brought down on him once more the sensation of loneliness.

Later, the feeling returns:

In all the white immensity he was the only moving creature. No bird quartered the sky, and if any animal skulked there, Joktar could not spot it. Loneliness ate into him and he redoubled his struggles to reach the cliffs.

A sequel?

There’s a reason that Joktar feels so lonely, and it’s not just the harsh landscape.

He learns that reason after he joins an outlaw group of trappers who ally with others to capture a space ship and fly to a nearby planet.

That’s where the shadowy people keeping tabs on Joktar finally come into the light and reveal who he is and why he’s so interesting.

In other Norton novels, such revelations tend to bring joy or peace, but, for Joktar, they raise difficult questions about what the future holds for him.

It would have been interesting if Norton had done a sequel to Secret of the Lost Race, but, even as I write that, I think the novel worked because of the punch of surprise at the end. A sequel probably would have been anticlimactic.

Patrick T. Reardon

4.12.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.