Seven Smith’s girlfriend Joy asks him about Jim Flood. “You speak of him with affection, yet he’s done such terrible things.” What kind of guy is he?

Seven, a 21-year-old Texas Ranger, once a greenhorn but now a veteran, isn’t sure how to answer. He tells her:

“I can talk about ‘im, all right, but I can’t guarantee to make a clear picture of him. Maybe it sounds dumb, but he’s kind of like the moon up there. Cold, but warm at the same time. Big. Alone. Over everythin’ else. And the only one of his kind.

“I’d trust him with anything I had, knowin’ at the same time he might turn on me at any minute.”

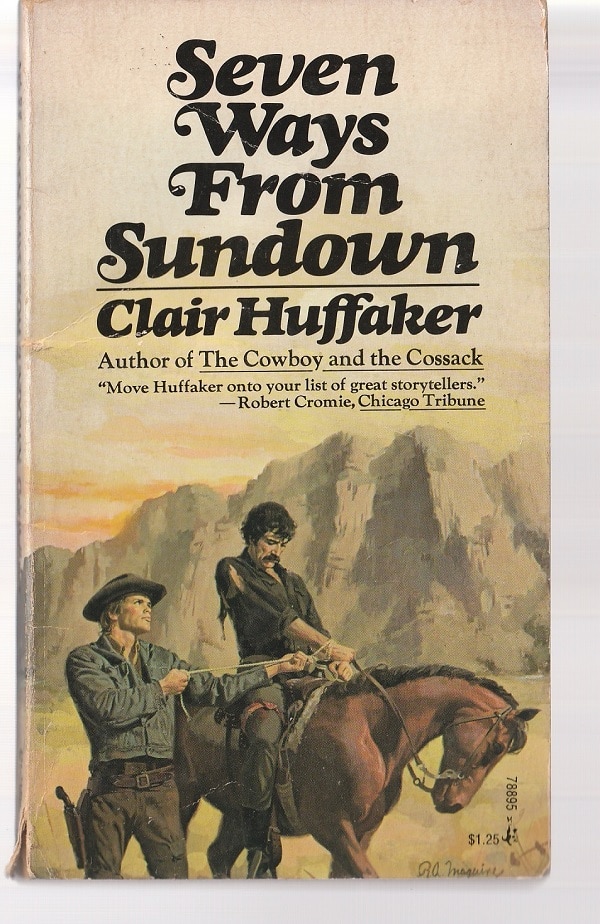

This comes near the very end of Clair Huffaker’s 1960 Seven Ways from Sundown, and it’s not the usual way a western ends, especially one that involves a lawman tracking down, capturing and bringing in a dangerous outlaw.

Quirky and cinematic

Huffaker, though, isn’t your usual western writer. His books are often quirky and have a cinematic quality.

In fact, several were turned into movies, often with Huffaker as the screenwriter. His novel Badman (1958) was filmed as the 1967 movie The War Wagon, starring John Wayne, and Nobody Loves a Drunken Indian (1967) as the 1970 film Flap, featuring Anthony Quinn.

For my money, Huffaker’s best novel is The Cowboy and the Cossack (1973), the story of more than a dozen Montana cowboys who are driving 500 longhorns across a 1,000 miles of Siberia, all the while feuding with their escort of Cossacks. It’s a collision of cultures that, eventually, is bridged. What’s amazing to me is that the story has never been filmed.

The first of Huffaker’s screenplays to reach the screen was his adaptation of Seven Ways from Sundown which arrived in theaters only a few months after the book was published.

Two Hot to Handle

As the novel opens, it’s 1884, and Seven Smith is a new recruit Ranger, sent out to join a detachment under Lt. Walter Herly.

On the second page of the book, the reader finds out that the title is more than just a figure of speech. Seven has reported to Sgt. Hennesey who, looking over the young man’s papers, notes that he’s been in the Rangers for a full nine days.

“How came you by the name Seven, Smith?”

“Pa didn’t wantta bother with fancy names. So he called us by the number of our comin’. There was One, and Two, and Three, and so on up to Thirteen. I was Seven. But Ma liked fancy names, so she always prettied ‘em up a little. Oldest boy was One for the Money. The next one was Two Hot to Handle. My honest-to-God name is Seven Ways from Sundown. But Seven is shorter.”

As I said, Huffaker is pleasantly quirky as a storyteller.

A charming one

Seven quickly gets on the wrong side of Lt. Herly because he takes a shine to Joy Harrington, the daughter of the trading post owner, and she takes a shine to him, and that ticks off the officer because he wants to court Joy himself.

By this point, it’s already clear to the reader that the lieutenant is a bad one after a scene in which, for no good reason, he shoots and kills two Indian children.

Then, to get Seven out of the way, Herly sends the young man and Sgt. Hennesey after the stone cold killer Jim Flood.

Eventually, it ends up that Seven alone has to track the killer down, and he does so with a little bit of luck and a lot of grit. But Flood isn’t your run-of-the-mill violent sociopath.

I mean, he’s still a sociopath, but he’s a charming one. And, for one reason and then another, he and Seven work together to survive a snowstorm, and they develop a friendship, even though Flood is virtually always tied up and Seven has to move heaven and earth to get the outlaw back to Texas, a thousand-mile journey.

Very last pages

Seven Ways from Sundown is a straight-arrow kind of guy, and he serves as a nice foil for the highly skilled and engagingly amoral Flood.

Seven Ways from Sundown is an engaging read with a lot of twists after that first one about Seven’s name.

Right up until the very last pages.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.31.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.