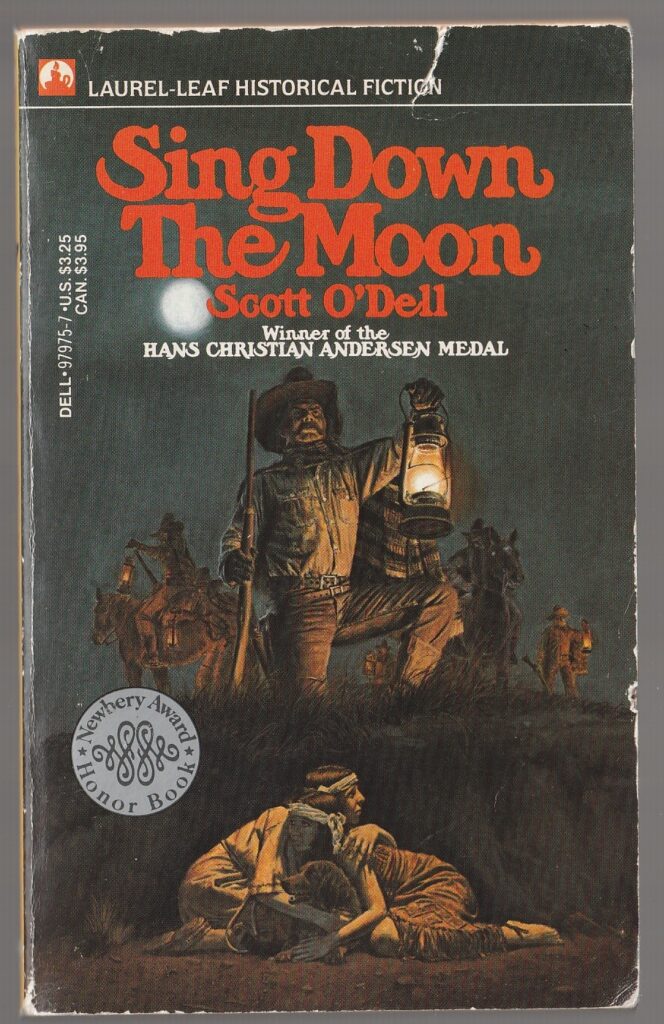

Scott O’Dell’s 1970 spare, steady and poignant novel Sing Down the Moon has a happy ending, but it tells a tragic story.

In the final pages of this story — written for teens and young adults but fitting and compelling for readers of any age — a sixteen-year-old Navaho mother and her husband Tall Boy have gotten away from the Bosque Redondo reservation outside of Fort Sumner in what is now central New Mexico.

They have retraced the Long Walk of three hundred miles that their people were forced to make to the camp where thousands of Apache and Navahos are interned with little food and no sheep, no hunting and little to do.

As the novel ends, the young couple have found a home for themselves in their tribe’s ancestral lands in what is now northeastern Arizona. Their son is born there, and they have found lost sheep.

My son touched the lamb once before the two moved away from us. He looked up at me and laughed and I laughed with him.

Rain had begun to fall. It made a hissing sound in the tall grass as we started toward the cave high up in the western cliff. Tall Boy had finished the steps and handholds and now stood under the cave’s stone lip, waving at us.

I waved back at him and hurried across the meadow. I raised my face to the falling rain. It was Navaho rain.

Her name

The story — told many years later by the mother — begins when she is fifteen and is kidnapped by Spanish slavers. She is taken to a nearby town and put to work for a white family.

She escapes with two other Indian girls and is about to be caught when Tall Boy, a strong vibrant youth a couple years older, kills the leader of the slavers with a lance. Moment later, however, Tall Boy is shot in the right shoulder and is never able to use his right arm again.

Throughout the novel, the name of the narrator is not given until very near the end — Bright Morning. It is as if O’Dell is saying that, until the young woman, now pregnant, is ready to escape the reservation, she isn’t ready to take on her name in all its fullness.

The tragedy

The “Navaho rain” in the book’s final sentence is a sign that Bright Morning, Tall Boy and their son have found a place where they can lead a rich life.

The tragedy of Sing Down the Moon is that the Navahos and Apache back at the reservation are facing futures that are barren and idle.

In a postscript, O’Dell explains that his novel focuses on what happened to the Navahos from 1863 to 1865, from being driven out of their villages, forced on the Long Walk and held at Bosque Redondo.

Bright Morning’s people were held captive at Fort Sumner until 1868, and some 1,500 hundred Navahos died during this time from smallpox and other diseases.

Then, they were set free with few supplies in a wind-swept desert with little rain, their permanent reservation.

Homes, orchard and fields

What the Navahos lost when they lost their ancestral village is detailed in three pages of O’Dell’s novel.

The Navahos, knowing that the Long Knives are coming, flee and hide up in the mountains. The soldiers try to find them and drive them out but fail. Nonetheless, the soldiers remain camped next to the village.

Then, as Bright Morning and a friend are watching from cover up above, they see a puff of smoke rise slowly above the village.

“Our homes are burning!”

The word came from the lookout who was far out on the mesa rim, closest to the village. It was passed from one lookout to the other…

“We will build new homes,” [her father] said.

Then the soldiers went to the tribe’s peach orchard.

Swinging the hatchets as they sang, the soldiers began to cut the limbs from the peach trees. The blows echoed through the canyon. They did not stop until every branch lay on the ground and only bare stumps, which looked like a line of scarecrows, were left.

Not only that, but the Long Knives stripped the bark from the stumps so that the tribe would have nothing to eat when they were starving. “Now they will go and leave us in peace,” said her father.

But they didn’t.

They spurred their horses into a gallop and rode through the cornfield, trampling the green corn. Then they rode through the field of ripening beans and the melon patch until the fields were no longer green but the color of red earth.

Now, her father said, they will leave. But they didn’t. They remained and remained until the tribe’s food ran out and the Navahos had to come down from their hiding place and surrender. And begin the Long Walk.

Sing Down the Moon is a tragic story.

Patrick T. Reardon

5.21.25

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.