I read a paperback copy of David Hare’s 1995 play Skylight that I found in one of the dozens of free little book boxes scattered across the neighborhoods I frequent on the Far North Side of Chicago.

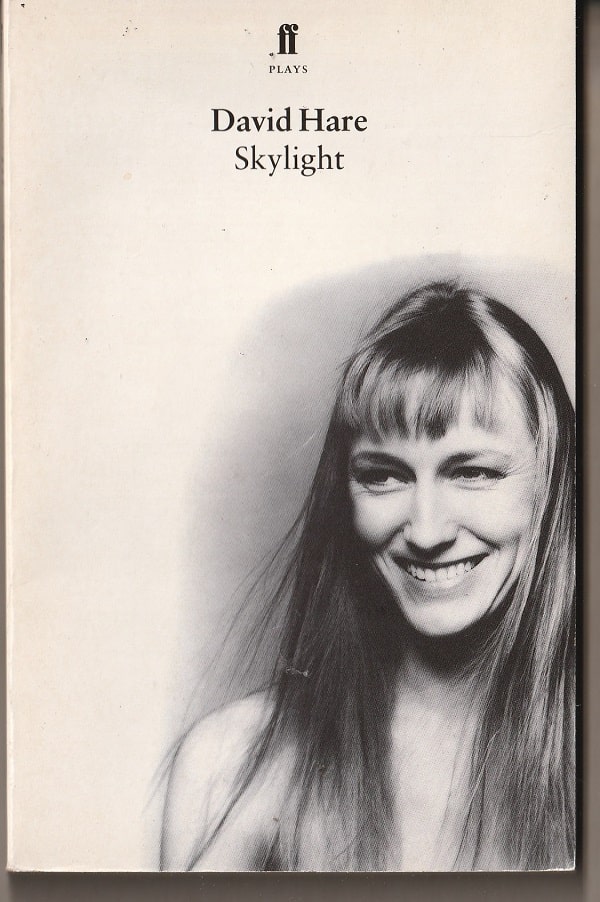

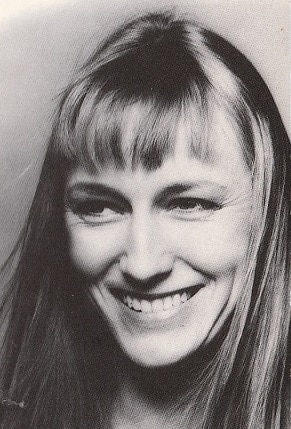

When I saw it in the book box, I was arrested by the white cover which featured, in the mid- and lower-right half a black-and-white photograph of a young woman with long hair, bangs and a wide smile. It stopped me for a moment, but I don’t read many plays, so I left it there.

Until the next time I looked in the book box. It was still there with its striking cover. And this time, I took it home.

Who, I wanted to know, was this interesting-looking woman? Did she have any connection to the play? Or was the image simply an illustration of a pretty woman?

I looked around the internet a bit and found that she was Lia Williams, the actress who created the character of Kyra Hollis when Skylight premiered at the Cottesloe Theatre of the National Theatre in London. In fact, the photograph was used for the cover of the playbill for that first run.

Williams starred across from Michael Gambon, taking the role of Tom Sergeant. The third actor was Daniel Betts as Tom’s son Edward. Williams and Gambon recreated their roles in a Broadway production in 1996 that garnered many Tony Award nominations. In London, Skylight won the Laurence Olivier Award, the British equivalent of a Tony, as the best play of the year.

The first meeting

It is an affecting drama detailing the first meeting of two lovers — the fiftyish Tom and the thirty-year-old Kyra — after three years apart.

For nine years, the two had worked closely together as Tom built his wealthy string of restaurants. During this time, Kyra lived with Tom’s family, becoming a friend of his wife Alice and a babysitter for their two children Edward and Hilary. And, for six years, she was Tom’s lover until Alice found out and Kyra abruptly walked out, cutting off contact.

The play is set in Kyra’s flat in a seedy neighborhood in North London. Edward, now eighteen, appears in scenes at the start and end of the play, but the heart of the drama is in two long scenes in the center in which the former lovers verbally dance around each other and their unsaid — and then said — feelings.

Too attractive?

Of course, Skylight is a play and would be much better to see on stage. That’s what I’m going to do if I get the chance. But the paperback of Hare’s script is well worth reading.

I’m left wondering, however, about that photo of Williams on the cover. Can the cover of a book be too attractive?

Anyone who does much reading knows that the cover of a book is an odd landscape. There’s a reason for that old saw about not trusting a book’s cover.

For instance, titles are anything but straight-forward. James Joyce named his great novel Ulysses not because it has a character by that name but because he’d written a modern version of Homer’s Odyssey.

Consider the bestseller and Pulitzer Prize finalist There There by Tommy Orange. It’s a novel about urban Native Americans, but the title doesn’t say that. You have to look at the back cover where the blurbs from famous writers clue you in. The role of the title here, as with most modern novels, is to entice the potential book buyer, to pique interest.

Many older novels, such as David Copperfield and Moby Dick, are more direct. But not all. When Pride and Prejudice was first published, how could you tell much of anything about the story it would tell?

The publishers of non-fiction books try to have their cake and eat it. They will choose an evocative title, and then add a subtitle that seems to give a clearer idea of what’s inside. But reader beware; The subtitle can easily promise more than the pages on the inside can deliver.

The cover package

As with the title and the subtitle, the image on the cover as well as the cover itself send a message to the would-be buyer. The cover of a light frothy novel, for instance, is likely to be colorful and bright while a book with a brooding or gloomy story will tend to have a lot of dark brown and black.

The photo on the jacket of a history of World War II will likely be a scene of war. The memoir of a celebrity is going to have that celebrity’s photo on the cover.

The goal of the cover package — title, illustrations, text, photos — is to get a reader to pick the book up and look inside. Or, online, to get a reader to look at the words of the publicist and of reviewers on the page.

So, the photo of Lia Williams got me to take Hare’s Skylight out of that book box, scan its pages and take it home. Mission accomplished.

Left wondering

I wonder, though, what happens when the cover doesn’t match the pages inside.

For me, this happens most often when I’m reading a non-fiction book and realize that I was hoodwinked by the promise of the subtitle. It leaves a bad taste in my mouth.

This can happen with the image or images on the cover although, in the case of Skylight, my feelings are somewhat ambiguous.

The photo of Williams seems to me to indicate that a woman is the central character of the play. And the publicity department at Faber and Faber would surely assert that she is.

But I was surprised, as I read Skylight, that Kyra isn’t the central character. She’s one of two central characters along with Tom. Yes, the play is set in her flat. And, yes, Edward’s there at the start and the end for a visit, and the meat of the play takes place when his father shows up there to see her after their long separation.

Tom is as important to the play as Kyra is. The cover doesn’t indicate that.

The Faber and Faber pr people, on behalf of all publishing pr people, would say that a book’s cover doesn’t have to — and can’t — fully encapsulate the story. Which is true.

Still, I’m left wondering.

And glad that the photo of Williams enticed me to read Skylight which I found compelling and captivating — and would never have read otherwise.

Patrick T. Reardon

11.22.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.