There are two types of Christians, according to French philosopher-theologian Emmanuel Mounier. There are those who see their faith as an adventure, a lively zestful engagement with the fullness of life, vibrant in the midst of the hustle-and-bustle and chaos and butt-and-ram of living. And there are the others.

Truth for them is a thing learnt within the strict limits of tranquility and utility. That it might be looked upon as an adventure irritates them. The Christian mystery is too huge for them, the Christian anguish too heavy. Nonetheless they desire the beneficence of certitude and the reassurance of the public triumph of faith. They love, too, the remnant of somnolent faith they still possess, for faith is always agreeable and they are not monsters, anything but monsters.

These are Christians, he writes with a “fear of freedom, fear of truth, fear of living.” Theirs is a “Christian feebleness.” They have “a servile taste for dependence and irresponsibility.” Theirs is a stunted Christianity.

Mounier, an important Catholic thinker and one of the guiding spirits of the twentieth-century personalist movement, dissects the two sorts of Christians in L’Affrontement Chretien (The Christian Confrontation), a 48-page essay he wrote in French in 1944.

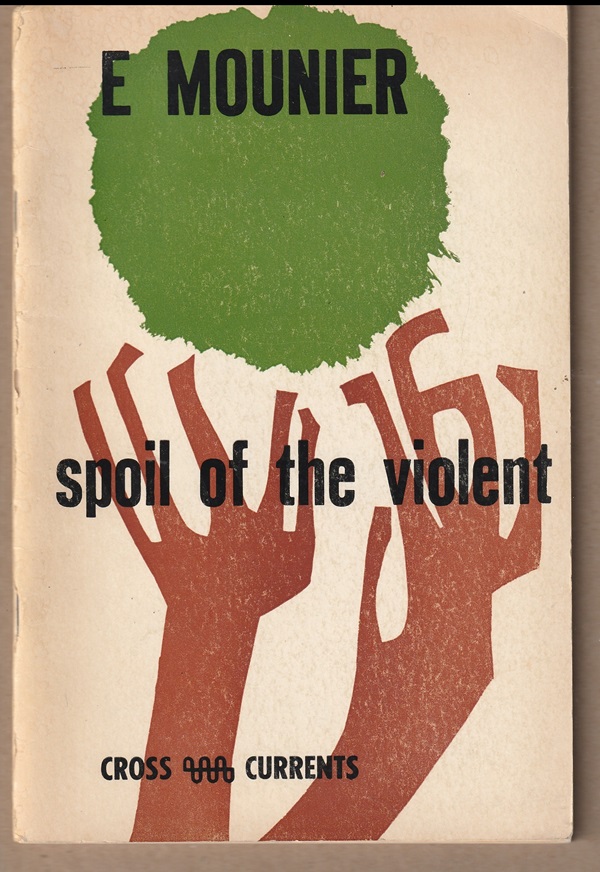

An English translation by Katerine Watson was published in 1955. It was republished in 1961 in CrossCurrents, an American journal committed to social justice and ecumenical understanding, and then published as Spoil of the Violent, a paperback pamphlet along with a second Mounier essay on Christian faith and civilization.

I am not sure how to understand the title Spoil of the Violent. It seems to me that the English version of Mounier’s French title, The Christian Confrontation, would have been much better.

Two confrontations

I say that because Mounier — whose thinking was an important influence for many progressive Christians, including Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin, the founders of the Catholic Worker movement — frames his essay as a dialogue with Friedrich Nietzsche.

Throughout the essay, Mounier offers italicized quotes from Nietzsche’s works about Christianity which the German philosopher saw as timid, tame and impotent, and then responds to them. The essay, in other words, is something of a confrontation between Nietzsche and Mounier over the nature of Christianity.

However, Mounier uses the essay, even more, to create a confrontation between the adventurous sort of Christian and the complacent, contented kind. In fact, Mounier implicitly argues that the Christians despised by Nietzsche are those who seek smallness and comfort, not the ones with a hugeness of real belief.

For instance, he writes that intellectual leaders of this “relaxed Christianity,” aim simply to “transform the call of adventure in the life of the Church into an inventory” and to turn “the human drama into a family outing and burning problems into a school exercise.”

“Security, economy, limited ambitions”

This state of mind he identifies as “bourgeois,” that is, middle-class and materialistic. He writes:

Christianity was evacuated with full official honors in order to install under the same name, and unobserved by the gapers, a utilitarian religiosity more or less dependent on commercial policy.

Faith, hope and charity gave place in the heart of the churchgoer-trader to the taste for security, economy, limited ambitions and social immobility….

The more Christianity became conservative, defensive, sulky, afraid of the future, the less it received that invigorating sap which comes to a society from its aggressive elements, its youth and its advance-guard.

This go along-get along approach to life honors calmness and placidity above all else. Calling it charity, such Christians seek “not to contradict and not to be contradicted; not to cause suffering and not to suffer; to offend nothing and not to be offended.”

It is an attitude that, Mounier writes, translates into “a code of moral and religious propriety whose chief concern seems to be to discourage outbursts of feeling, to fill up all chasms, to apologize for audacity, to do away with suffering, to bring down the appeals of the Infinite to the level of domestic conversation, and to tame the anguish of our state.”

“Violent leaps”

Real Christianity, however, asserts Mounier, is a muscular, brawny endeavor, anything but calm and placid:

Spiritual time is not a continuous unfolding of consolation, a happy and spontaneous flowering. It beats in the category neither of happiness nor of progress. It is made up of violent leaps, of crises and nights, interrupted by rare moments of fullness and peace.

It resembles more the poet’s time than the time of the engineer.

An engineer finds answers. A poet asks questions. That’s the confrontation that Mounier presents — the confrontation between navel-gazing and embracing the hurly-burly of living:

The humblest Christian life beats with the pulse of the universal community; it breathes the air of great spaces alike in the little dressmaker’s workroom and the local government official’s office.

“Waiting upon the Extraordinary”

Real Christianity is not about systems and stasis. Indeed, it turns its back on those. It turns its back, “not on every Christian philosophy, but on every Christian philosophical system; not on all certitude, but on any permanent dwelling within certitude; not on every Christian temporal order, but on every Christian temporal utopia; not on joy, but on happiness; not on peace, but on tranquility; not on plenitude, but on satisfaction.”

Real Christianity is the antithesis of satisfaction. It is about movement and engagement. And Mounier goes on:

It does not make of the Christian life a life substantially anguished, but it insinuates the thorn of anguish into the heart of every blessedness, save only the last blessedness of all….

One cannot conceive of the Christian life which did not carry in its heart this obscure and anxious waiting upon the Extraordinary.

“Transfiguration, not domestication”

In talking of a “thorn of anguish,” Mounier is recognizing the pain of living, even with faith. He is recognizing that the search for a life of comfort is refusal to live. Indeed, Mounier writes much about attempts to domesticate Christians, to isolate them from the kaleidoscopic diversity of living, to find a safe place for them. But, he writes, “domestication is not a proud fate for a Christian.” And he goes on:

St. Francis did not castrate the wild beasts, he subdued them; they came up to him to rub their muzzles in the skirts of his monk’s robe, still quivering and ready, I imagine, to leap and race in his service. This resilient step, this restrained vigor and this vibrant willingness to be used should be the fruit of instinct disciplined by ascesis. Transfiguration, not domestication…..

That, at its heart, is Mounier’s argument: Christianity is about a world in which transfiguration takes place. That doesn’t happen in a tame world.

One last note: Mournier died of a heart attack in 1950 at the age of 44. His essay is densely argued and poetically envisioned. Nonetheless, he was a person of his time, and modern readers should be warned that he portrays the domestication of Christians as a feminization. It is the sort of metaphor that would not be used today.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.23.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.