There are a goodly number of alternative-history novels that imagine what life would have been like if Hitler had won World War II, and I’ve read my share.

Three of the better ones are The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick (1962), Fatherland by Robert Harris (1992) and SS-GB by Len Deighton (1978).

Dick’s novel is set 15 years after Capitulation Day in 1947 focuses on how various Americans cope in a partitioned United States where Japanese and Nazi leaders are jockeying for advantage.

The Harris book is set in Germany in 1964, nearly two decades after the end of the war in which Germany conquered Europe and Great Britain while the U.S. beat Japan and remains allied with the Soviet Union. The story involves a Berlin detective and an American reporter who work together to document the Holocaust.

While, in both, the war is long over, that’s not the case in Deighton’s SS-GB.

As the story opens, Britain’s defeat by the Germans is still fresh and painful for the English.

This gives an unusual emotional edge to the novel that distinguishes it from Deighton’s many other best-selling suspense books, such as The IPCRESS File and

Funeral in Berlin.

Douglas Archer, the detective at the center of SS-GB, has to deal with convoluted events involving crime and spies and secrets, but, even more, he has to do so while carrying the burden, like all other Britons, of having lost the war and their nation to an occupying, totalitarian invader.

“He’d do his work”

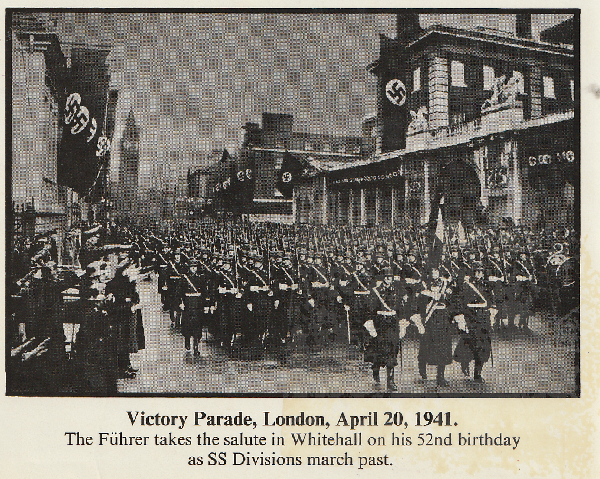

It is November, 1941, just nine months after government officials signed the instrument of surrender. Instead of staying on the continent as he did in real life, Hitler went ahead and invaded the island nation, crushing all opposition.

Detective Supt. Archer is a tall, thin, Oxford-educated 30-year-old, known as “Archer of the Yard” for his skill at solving murders. His assistant is the middle-aged veteran Sgt. Harry Woods, “a policeman of the old school, scornful of paperwork, filing systems, and microscopes. He liked to be talking, drinking, interrogating and making arrests.”

The two men make an odd team in Scotland Yard’s Murder Squad, but Archer would never have gone into police work if it hadn’t been for Woods. Harry was the copper walking a beat in Archer’s childhood who befriended the lonely rich boy whose father had been killed in the Great War.

For Harry, the fighting would never end. His generation, who’d fought and won in the filth of Flanders, would never come to terms with defeat.

But Douglas Archer had not been a soldier. As long as the Germans let him get on with the job of catching murderers, he’d do his work as he’d always done it. He wished he could get Harry to see it his way.

The King in the Tower

Archer’s desire to lose himself in work is rooted in his own deep grief. His wife was killed during the street fighting that demolished the couple’s home as well as the neighbor’s house in which she had taken refuge. Their young son Douggie was at school at the time.

Now, father and son live in a room in the home of Mrs. Sheehan, the mother of one of Douggie’s classmates and wife of a British soldier being held in a POW camp.

Archer is going about his daily business when he’s notified that a man with what look like sun-burned arms has been found murdered at a likely safe house for the Resistance, and, as Archer goes into his investigation, he finds himself being caught up and battered about by large forces.

Such as the interservice rivalry between the SS, Gestapo, Abwehr and the German Army which was given the plum assignment to run Great Britain while holding King George VI in the Tower of London. (Winston Churchill has already been shot by a firing squad.)

No Colonel Klink

And such as the internal SS conflict between two of Archer’s bosses, General Fritz Kellerman and a Nazi Standartenfuhrer named Oskar Huth. Deighton describes Kellerman as a man whose

enthusiasm for good food and drink provided a rubicund complexion and a slight plumpness which, together with his habit of standing with both hands in his pockets, could deceive the casual onlooker into thinking Kellerman was short and fat, and so he was often described.

He’s a champion chess-player and a skilled equestrian, but many, including Archer, tend to underestimate him. Indeed, Deighton may have been consciously working to bring to the reader’s mind Colonel Klink of the Hogan’s Heroes TV show.

However, Kellerman is no fool as Archer — and Huth — find out.

The Resistance and nuclear secrets

Huth — “a powerful muscular figure with an energy in his stride and demeanor that believed the hooded eyes that made him seem half-asleep” — aims from his arrival as a personal representative of Heinrich Himmler to undercut Kellerman. A man harsh and brutal in his dealings with others, Huth has soon gathered files of documents showing how the General has personally profited from his high position.

Yet, even as Huth and Kellerman are clashing, diehard Resistance fighters, including Archer’s secretary and former lover Sylvia Manning, are working — weakly and essentially with little hope — to disrupt the occupiers.

And, to complicate matters even more, those four rival arms of the German military-police-intelligence operation are working against each other in the effort to develop nuclear weapons.

And the Resistance is hoping to use the existence of atomic secrets to tempt the Americans — fighting the Japanese in the East, but on the sidelines in the European conflict — to covet them for their own military use.

Meanwhile, with the King locked up in the Tower, efforts to establish an accepted British government in exile are failing.

“You’re English”

Finding himself in the middle of all of these power struggles, Archer no longer has the luxury of simply going about his police business without having to think about the darker aspects of daily existence.

At one point, when Huth orders the headmaster at Douggie’s school as well as all of its teachers and older boys to be trucked away to a detention camp, the headmaster grabs at Archer:

“Tell them. You’re English, I know you are…Tell them I’m innocent.”

Douglas went rigid with shame. A soldier prised the headmaster’s fingers away.

“Clap your hands”

Then, in one of the novel’s most poignant scenes, one of the teachers in the lorries is trying to comfort an older schoolboy.

A grey-haired man with bent spectacles smiles at the boy and in a thin piping voice began to sing:

“If you’re happy and you know it, clap your hands.”

He clapped his hands. The wavering tuneless voice could be heard in the parade-ground silence of the school yard. A second voice joined in the old Boy Scout song,

“If you’re happy and you know it, clap your hands,”

And there was the sound of a dozen or more hand claps, and now the child joined in, still crying. The Germans looked round for orders to stop the singing but when no such order came, did nothing.

But, of course, Brits would respond with a stiff upper lip to the terrifying experience of being dragged out of their school building and facing the prospect of a camp imprisonment. They respond with a coping mechanism from their own pleasant culture that is beyond inadequate before the hard-faced efficiency of the brutal German military bureaucracy.

It’s enough to break your heart.

“A deep, dark vortex”

And it seems to break Archer’s heart. And, for that matter, Deighton’s, as well.

Archer turns away from the school for the walk home, holding his son’s hand “as if it was the only thing in the world he had.” And he faces a new realization:

Until now, he’d found it possible to work with the Germans. After all, he’d been hunting murderers and he’d not had to search his conscience about that. But increasingly he found himself being drawn down into a deep, dark vortex, moving at a snail’s pace, as things always happen in a nightmare. And yet he had no way of escape.

Sharp and bitter

Deighton, who was born in London in 1929, has lived abroad since the age of 40. So, he’d been an expatriate for nearly a decade when he wrote SS-GB.

Nonetheless, while the book exhibits his usual compelling and highly readable suspense story, it also has the unusual subtext of the adaptation that Britons would have had to make in the face of a German occupation. Like the scene of the teachers and school boys singing, “If you’re happy and you know it,” every mention that Deighton makes of such adaptations is sharp and bitter.

Here, for instance, is a savage paragraph that describes part of the scene that Archer takes in when he attends a black-tie party at the mansion of a shady art importer:

Here too were the men of Whitehall; top-ranking bureaucrats whose departments continued to run as smoothly under the German flag as they had under conservative and socialist governments. There were nobility too, placed in the guest list with that seemingly artless skill that a gardener uses with a few blooms that flower in the heart of winter; nobility from Poland, France and Italy as well as the home-grown variety. And always there were businessmen; individuals who could get you a thousand pairs of rubber boots, or a hundred kilometres of electrified fencing; three crosses and nine long nails.

“Three crosses and nine long nails”

If you’re ripping through the novel as a page-turning suspense reader, sprinting along with the plot, you might miss the reference to Calvary and the Passion of Jesus.

There are others. As an office decoration, Huth pulls out Piero della Francesca’s fifteenth-century Flagellation of Christ, described by one critic as “”the greatest small painting in the world.” No mention is made of where he got the priceless artwork.

At the party Archer attends, he spots a grouping of guests around a Crucifixion by one of the Cranach family.

Later, in the room of a German soldier, Archer notices on the wall “a small antique crucifix, the taut and angular Christ unmistakably German in its stylized agony.”

A near thing

“Stylized agony” — there’s another phrase.

Deighton knows how to write a popular novel that will sell a great many copies and make him and his publisher a lot of money. That’s what he does in SS-GB.

Think of that as the style in which he exhibits the agony. Think of that as the setting in which he offers a heartfelt lament for what he and other Britons would have had to have gone through if Hitler had invaded Great Britain as planned.

It was a near thing.

And SS-GB lets us know the pain and suffering that might easily have been inflicted on the British. It’s more than a bit harrowing.

Patrick T. Reardon

3.7.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.