One of my favorite poems in Haki R. Madhubuti’s new, career-spanning collection Taught by Women: Poems as Resistance Language is “Big Momma,” originally published in 1970.

Back a half century ago, Madhubuti was still known as Don L. Lee, and, at 28, he was a leading artistic, political and social revolutionary, a member of the Black Arts Movement that asserted, in contradiction to the White mainstream, the richness of Black life.

Black art, Black history, Black thought — the Black struggle to find meaning in existence, long denigrated by the White power brokers and thought-shapers in academia and throughout American society — not only had intrinsic value, he and other activists asserted, but also had something to offer to people of all races.

Not just in terms of playing basketball with flair or singing the blues or tap-dancing up a storm — not just as privileged entertainers. Much more, as creators of beauty, as philosophers, as social theorists, as frontline reporters from the daily friction of America’s Black and White worlds.

The Big Momma of the poem, an older relative whom Madhubuti visited weekly, tells the young poet that she is puzzled by all the changes that have been going on since the Civil Rights Movement, and the Black Power Movement, and the Black Is Beautiful Movement:

she’s somewhat confused about all this blackness

but said that it’s good when negroes start putting themselves

first and added: we’ve always shopped at colored stores,…

Nonetheless, she’s candid about the drugs and other self-defeating activities of many Blacks who “fight each other over who get the mostest.” After leaving her and heading down the snowy sidewalk toward 43rd Street, the poet pictures Big Momma:

At sixty-eight

she moves freely, is often right

and when there is food

eats joyously with her own

real teeth.

Extraordinary

Haki Madhubuti is now 78, a decade older than Big Momma was when he wrote her poem.

Unlike many 1960s radicals, White and Black, Madhubuti remains a leading Black artistic, political and social revolutionary — a poet who still writes for other blacks about the Black experience from deep inside the community; the founder and still head of the 53-year-old Third World Press, the largest and oldest Black publishing house in the U.S.; and co-founder of an Afro-centric elementary school and a high school designed to provide African American children with a solid grounding in who they are and who they come from.

After a lifetime of activism, he isn’t slowing down although Covid-19 restrictions and cautions have ended, for the moment, his wide travels as a frequently requested speaker on Black life, Black empowerment and issues facing African Americans and their fellow White citizens.

Nonetheless, his new book represents a summing-up of his life and career, and, given that, it is extraordinary that he has decided to focus it on the impact of women in his life and to title it Taught by Women.

It is extraordinary because, of course, the history of the United States — well, of the world — has always been patriarchal. Women have rarely been permitted to exert leadership and rarely been accorded their due when they have influenced events.

This has been true in mainstream America — and also true among this nation’s radicals through the decades, White and Black. Ida B. Wells-Barnett is an example of a rare women who, through her urgency, intelligence and hard work, rose to become the major anti-lynching advocate in U.S. history.

Shaped him as person, poet, leader

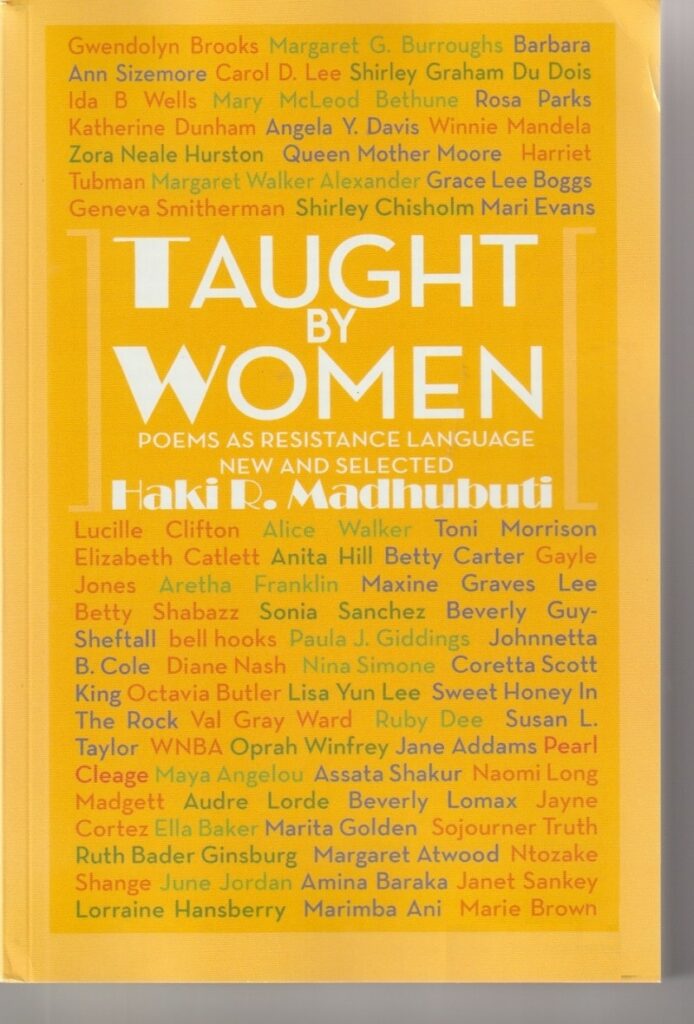

For Taught by Women, Madhubuti has filled the front and back covers, as well as the two inside covers, with the names of more than 100 women who have helped shape him as a person, poet and leader.

The first four are the most important: his wife Carol D. Lee, also called Safisha Madhubuti, a nationally recognized educator; his artistic mentor and mother-figure Pulitzer-Prize-winner poet Gwendolyn Brooks; and two women who were key in his development as a Black thinker, Margaret Burroughs, the Chicago writer, artist and founder of the DuSable Museum of African American History, and Barbara Ann Sizemore, the first African American woman to head the public school system in a major city (District of Columbia).

Most of the women on the book’s covers are African American. Some names will be familiar to White readers, such as Anita Hill, Michelle Obama, Shirley Chisholm and Coretta Scott King. Many more, though, should spur searches at Wikipedia or elsewhere online, such as Audre Lorde, Mamie Till-Mobley, Nikole Hannah-Jones, Jackie Taylor, Ann Petry and Barbara Smith.

White, Hispanic, Asian and Native American women, perhaps 20 or 30, are featured, among them Margaret Atwood, Joy Harjo, Jane Addams, Elizabeth Warren, Arundhati Roy, Sandra Cisneros, Jill Lepore and the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

In listing these women, Madhubuti is saying that he has learned from them, even from those he has never met. For some, he is tipping his hat in thanks for public deeds and public words. For others, he is recognizing a more immediate impact.

Three of the listed women are, in another unusual acknowledgement for a male leader, his three daughters: Laini Madhubuti, Regina Alcantar and Mariama Richards.

And one name on the front cover is a recognition of a woman whose life provided deeply agonized lessons for Madhubuti — Maxine Graves Lee, his mother.

“Music unemployed”

Taught by Women is a second installment of Madhubuti’s autobiography. The first was YellowBlack: The First Twenty-One Years of a Poet’s Life, published in 2006. A mix of poetry and poetic prose, this memoir is an achingly painful account of growing up acutely poor as the son of a beautiful, light-skinned woman who, through the men who lusted after her, fell into drug addition, physical abuse and prostitution.

Eight poems about his mother are included in Taught by Women, including “Helen Maxine,” which features these lines:

My mother was so beautiful that she not only stopped

cars, she stopped buses…

She was music unemployed.

She wrapped her body in clothes that refused to hide

the nature of her desires…

Her clothes got in the way of men

taking them off.

Another poem “Helen Maxine: Three” tells of how the teenaged Don L. Lee would, at times, have to go out in the neighborhood to search for his missing mother. This resulted in confrontations with men who had paid her for the night.

I, at 6’1”, 131 pounds, did not inject too much

fear in the hearts of men much larger than me.

This was my advantage: I carried a lead pipe in

my belt and could use it and the language of

the streets with a righteous certainty that

would force most men to stand down before

confrontation.

“Saving my life”

In a short introduction to Taught by Women, “Why Women?” Madhubuti writes that he has learned to be “pro-girl and woman” and that it “requires serious listening and specialized learning, advanced thought, care, action and language that highlights Black music, poetry and visual art which I received from my mother — a woman who worked and died in the sex trade of the 1950s.” He goes on:

Black ignorance, enslavement and anti-religious thought killed her; I, her only son, am able today and tomorrow to act and state with finality, stop. And again thank you to Black women and the world of women for saving my life.

“Enough said”

A goodly number of the poems in Taught by Women are lighter in tone, many of them celebrations of love, often verses to recognize a marriage or an anniversary of a male and female couple.

However, Madhubuti, who earlier in his career was critical of homosexuality, has mellowed and learned from women, including lesbians, and he writes in a section of the 2009 poem “Liberation Narratives”:

janet liked girls

and told them so,

robert liked boys

and kept it a secret.

both grew into teenagers

still liking girls,

still liking boys.

each kept their desires to themselves.

in the 21st century parts of the world

began to mature and finally

understood why

janet loved women

and

robert loved men.

they were born that way,

enough said.

One playful and endearing poem is “Laini,” an eight-line work about his daughter heading off to New York City and then coming back home for a visit. Madhubuti, a vegan, ends it this way:

I cried when she returned

whole & enlarged & well,

still avoiding vegetables & housework.

“As the women go”

Lest those lines give the reader the idea that Madhubuti, whose life has been defined by speaking truth to power as well as truth to his community, has turned into a softy, forget it.

Taught by Women is subtitled Poems as Resistance Language for a reason. The controlled anger and clear-sighted vision that has fueled Madhubuti’s writing for six decades is on display on virtually every page of the book, even and especially in celebratory poems.

For one thing, speaking up on behalf of women — indeed, acknowledging their importance — is as counter cultural in modern-day America as you can get. For instance, in the face of patriarchal western civilization, he begins “Magnificent Tomorrows” this way:

flames from sun

fire in during rainbow nights.

the women are colors of earth and ocean —

earth as life,

the beginning waters,

magnificent energy.

as the women go, so go the people,

determining mission,

determining possibilities.

“Debt is owed”

The oppression of women is part and parcel to the repression of others — all people of color, LGBTQ people, anyone whom the white male American power structure has deigned to be less than human — such as in the U.S. Constitution which identifies a Black man as 3/5 of a White man.

In the four-page poem “Reparations: The United States’ Debt Owed to Black People,” Madhubuti details the myriad ways that African Americans have been abused, violated, oppressed, cheated, enslaved and raped.

Then, midway through, he opens the poem up to include Native Americans, victims with Blacks of “two genocides” by Whites.

Debt is owed to First Nations People and Black people forced:

to laugh when there is nothing funny,

to smile when they are in pain,

to demean themselves on stage, in film, television and videos,

to dance when their hearts hurt,

to accept delusion as truth…

to see clearly and act as if they are blind,

to act stupid in the eyes of a fearful rulership,

to say yes when they really mean No!…

Madhubuti ends this poem with a question that goes to the heart of the Black Lives Matter movement and the waves of unrest across the nation over the routine killing of unarmed black people by police: “What does America owe First Nations ‘Indians’ and Black people?”

And here is how he estimates the debt:

What is the current worth of America? Or

count the stars in all the galaxies and multiply in

dollars by 100 billion,

for a reflective start.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.20.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.