Reader:

This review is going to deal with Mark Twain’s 1885 novel The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and, because of that, it will include a particular term that, today, is highly offensive.

If that makes you too uncomfortable, please don’t read any further.

Also, for comparison purposes, I will mention D. H. Lawrence’s 1928 novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover where another word, viewed as offensive for other reasons, is frequently used.

Finally, in writing about Huckleberry Finn, I am writing as a white American. I know that an African-American would read this book with a different set of experiences, sensitivities, interpretations and insights than I bring to the task.

The word

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain uses the word “nigger” 214 times. When I read the book, I kept track of the number of pages on which the word appeared, and that came to 71, or about 31 percent of the total 230.

By contrast, in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, published eight years earlier, Twain used the word “nigger” only nine times — on five of the book’s 161 pages, three percent.

I’m certainly no expert on Mark Twain, but I have a theory about Huckleberry Finn.

Readers today are uncomfortable to read the word “nigger” used on so many of the novel’s pages. My suspicion, though, is that readers in the 1880s were also made uncomfortable by the word.

Yes, I know it was a word commonly used at the time by many American whites. Still, even then, I believe, it was seen as somewhat uncouth language, especially in the North.

Consider the other American writers of the time. None of them used the word, as far as I know or can determine — not William Dean Howells, or O. Henry, or Sarah Orne Jewett. Certainly not Henry James. Not even the Southern writer Joel Chandler Harris in his many Uncle Remus stories.

Consider the other American writers of the time. None of them used the word, as far as I know or can determine — not William Dean Howells, or O. Henry, or Sarah Orne Jewett. Certainly not Henry James. Not even the Southern writer Joel Chandler Harris in his many Uncle Remus stories.

Again, I have to admit that I’m not an expert. Still, I’d be surprised if someone were able to show me another popular late-19th century American novel that used the word “nigger” at all, much less more than two hundred times.

Again, for contrast, consider that, in 1928, D. H. Lawrence caused a huge literary uproar when, in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, he used the work “fuck” or derivative versions 26 times. Readers were shocked.

I think Twain meant to shock his readers.

The uncouthness and the setting

This shock of uncouthness had a purpose, as did the setting of the novel.

Because the events of the book take place in 1850s America, three decades in the past — before the Civil War, before the abolition of slavery, before whites throughout the nation found themselves living with millions of free blacks — the reader of the book when it was first published had a kind of deniability: “What’s happening here on the page is something that occurred a long time ago. It has nothing to do with my present-day life.”

In a similar way, the uncouthness of Huck’s language, particularly the use of the word “nigger,” gave readers of the time a frisson of transgressing the rules of polite language. Again, there’s deniability since the reader isn’t the transgressor, it’s that playful rube Huck.

More important, the use of “nigger” distracted the reader then — and distracts the reader today — from feeling the full impact of Twain’s deeply subversive main theme in Huckleberry Finn.

That theme could be stated this way: good people can be silly, bad people can be pitiable, rich people can be stupid, white people can be wrong, and black people can be noble.

No person is defined by his or her spot on the ladder of society. No person is without sin or redeeming humanity. No person can be written off.

And a black and a white can be friends.

“Awful cruel”

Case in point: The Duke and the King, also called the Dauphin. These men are scoundrels of the first order, going from town to town with cons and scams, trying to bilk, for instance, the newly orphaned Wilks nieces out of their inheritance and even going so far as to sell Huck’s black friend and their helpmate Jim back into slavery.

Their actions are truly despicable. And they are truly, as Huck says, “rapscallions.” Yet, for Huck — and for Twain — these two men are human beings, despite their chicanery. And, in one of the most poignant scenes in the novel, Huck tells of walking with Tom Sawyer into town at night:

“…here comes a raging rush of people with torches, and an awful whooping and yelling, and banging tin pans and blowing horns; and we jumped to one side to let them go by; and as they went by I see they had the king and the duke astraddle of a rail—that is, I knowed it was the king and the duke, though they was all over tar and feathers, and didn’t look like nothing in the world that was human—just looked like a couple of monstrous big soldier-plumes.

“Well, it made me sick to see it; and I was sorry for them poor pitiful rascals, it seemed like I couldn’t ever feel any hardness against them any more in the world. It was a dreadful thing to see. Human beings can be awful cruel to one another.”

It’s a measure of Twain’s skill as a writer that in just a few lines he could turn the Duke and the King from entertainingly humorous swindlers into figures of sorrow — “poor pitiful rascals.”

And it’s a measure of his insight as a social critic that he could recognize how wrong-headed it is to be so “awful cruel” to other human beings, even those deserving of punishment.

“Kill them!”

Similarly, Huck really likes the Grangerfords, the rich aristocratic family who take him in:

“It was a mighty nice family, and a mighty nice house, too. I hadn’t seen no house out in the country before that was so nice and had so much style. It didn’t have an iron latch on the front door, nor a wooden one with a buckskin string, but a brass knob to turn, the same as houses in town. There warn’t no bed in the parlor, nor a sign of a bed; but heaps of parlors in towns has beds in them. There was a big fireplace that was bricked on the bottom, and the bricks was kept clean and red by pouring water on them and scrubbing them with another brick; sometimes they wash them over with red water-paint that they call Spanish-brown, same as they do in town. They had big brass dog-irons that could hold up a saw-log.

“There was a clock on the middle of the mantelpiece, with a picture of a town painted on the bottom half of the glass front, and a round place in the middle of it for the sun, and you could see the pendulum swinging behind it. It was beautiful to hear that clock tick.”

The Grangerfords have a great life. They have it made. But being rich and comfortable and savvy at business doesn’t save them from the family’s fatal flaw — its feud with the Shepherdsons.

They can’t save themselves from themselves, and the result is constant bloodshed and violence, as Huck finds one day when, in an orgy of killing, the head of the Grangerfords and two of his sons are slain, and the young son Buck, Huck’s good friend, is on the run as Huck watches from a tree:

They can’t save themselves from themselves, and the result is constant bloodshed and violence, as Huck finds one day when, in an orgy of killing, the head of the Grangerfords and two of his sons are slain, and the young son Buck, Huck’s good friend, is on the run as Huck watches from a tree:

“All of a sudden, bang! bang! bang! goes three or four guns—the men had slipped around through the woods and come in from behind without their horses! The boys jumped for the river—both of them hurt—and as they swum down the current the men run along the bank shooting at them and singing out, ‘Kill them, kill them!’ It made me so sick I most fell out of the tree. I ain’t a-going to tell all that happened—it would make me sick again if I was to do that. I wished I hadn’t ever come ashore that night to see such things. I ain’t ever going to get shut of them—lots of times I dream about them.”

In a late 19th-century American society in which the upper classes were seen as, well, better than everyone else, this section of the novel must have been particularly unsettling. As it is today.

“Mooning around”

And then there are Uncle Silas Phelps, a gentle preacher who “trusts everybody,” and Aunt Sally, two good, good-hearted people, the salt of the earth. They have accepted responsibility to keep Jim, identified by the Duke and King as a runaway slave, locked up until his master can be found.

And they are so compassionate that, as Jim tells Huck and Tom Sawyer, “Uncle Silas come in every day or two to pray with him, and Aunt Sally come in to see if he was comfortable and had plenty to eat, and both of them was kind as they could be.”

Yet, for Twain, even the saints among us can be silly, as is Uncle Silas when he gets caught up in Huck and Tom’s increasingly complex lies in the final Marx-Brothers-like chapters of Huckleberry Finn.

At one point, after the two friends let rats get the run of the Phelps house, Aunt Sally blames Uncle Silas for failing to block up the rat-holes in the basement. Huck and Tom, feeling guilty, decide to do a good turn and block them up for him, but that ends up leaving Uncle Silas very confused:

There was a noble good lot of [rat-holes] down cellar, and it took us a whole hour, but we done the job tight and good and shipshape. Then we heard steps on the stairs, and blowed out our light and hid; and here comes the old man, with a candle in one hand and a bundle of stuff in t’other, looking as absent-minded as year before last. He went a mooning around, first to one rat-hole and then another, till he’d been to them all. Then he stood about five minutes, picking tallow-drip off of his candle and thinking. Then he turns off slow and dreamy towards the stairs, saying:

“Well, for the life of me I can’t remember when I done it. I could show her now that I warn’t to blame on account of the rats. But never mind—let it go. I reckon it wouldn’t do no good.”

“Cared just as much”

And then there’s Jim.

Throughout The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Jim is constantly called “nigger,” as is any other black person, whether slave or free.

Oddly, the word “slave” or “slavery” is rarely used in the novel, only 11 times. To use the word “slave” is to emphasize the complete domination of the person by the master. In this context, is it more respectful to refer to the person as a “nigger”? I’m not sure that’s true. But I’m not sure it isn’t.

I am sure that Jim is one of the richest, most human characters in Twain’s novel.

Yes, he is painted at many points as superstitious and gullible. But so is Huck. Yes, he is willing to take orders from a white, even a white boy of 13. But, in Jim’s world, whites were the ones who had the power and the education to know stuff that Jim didn’t.

Still, in perhaps the most poignant scene in the novel, when Jim pines for his family, only the coldest-hearted reader could be unmoved. It starts on the raft when Huck wakes up to find Jim “sitting there with his head down betwixt his knees, moaning and mourning to himself.” Huck doesn’t mention this to Jim because:

“I knowed what it was about. He was thinking about his wife and his children, away up yonder, and he was low and homesick; because he hadn’t ever been away from home before in his life; and I do believe he cared just as much for his people as white folks does for their’n.”

This may be the key sentence in the book. It dawns on Huck that, even though Jim is black, “he cared as much for his people as white folks does for their’n.”

This is a clear, firm recognition of Jim’s full humanity.

Indeed, Huck is amazed at his recognition of the human Jim:

“It don’t seem natural, but I reckon it’s so. He was often moaning and mourning that way nights, when he judged I was asleep, and saying, “Po’ little ’Lizabeth! po’ little Johnny! it’s mighty hard; I spec’ I ain’t ever gwyne to see you no mo’, no mo’!” He was a mighty good nigger, Jim was.”

“I bust out a-cryin”

The poignancy of this scene is heightened when Huck gets Jim talking about his wife and children, and Jim tells Huck how conscience stricken he is that he treated “my little ’Lizabeth so ornery.” He explains that she was only four-years-old and had just gotten over scarlet fever when he told her to shut the door.

Jim tells Huck, “She never done it; jis’ stood dah, kiner smilin’ up at me. It make me mad; en I says agin, mighty loud, I says: “‘Doan’ you hear me? Shet de do’!’” Elizabeth still did nothing so, Jim says:

“I fetch’ her a slap side de head dat sont her a-sprawlin’. Den I went into de yuther room, en ’uz gone ’bout ten minutes; en when I come back dah was dat do’ a-stannin’ open yit, en dat chile stannin’ mos’ right in it, a-lookin’ down and mournin’, en de tears runnin’ down. My, but I wuz mad! I was a-gwyne for de chile, but jis’ den—it was a do’ dat open innerds—jis’ den, ’long come de wind en slam it to, behine de chile, ker-BLAM!—en my lan’, de chile never move’!

“My breff mos’ hop outer me; en I feel so—so—I doan’ know HOW I feel. I crope out, all a-tremblin’, en crope aroun’ en open de do’ easy en slow, en poke my head in behine de chile, sof’ en still, en all uv a sudden I says POW! jis’ as loud as I could yell. She never budge!

“Oh, Huck, I bust out a-cryin’ en grab her up in my arms, en say, ‘Oh, de po’ little thing! De Lord God Amighty fogive po’ ole Jim, kaze he never gwyne to fogive hisself as long’s he live!’ Oh, she was plumb deef en dumb, Huck, plumb deef en dumb—en I’d ben a-treat’n her so!”

The image of Jim weeping out of his love for Elizabeth and his shame for slapping her is the heart of Twain’s story. This is not a novel about Huck’s adventures. It’s a novel about a man who is as much a person as any reader. Regardless of color.

“All right, then,…”

About 50 pages later, Huck has pangs of conscience about helping Jim escape Miss Watson — “stealing a poor old woman’s nigger that hadn’t ever done me no harm” — and decides to write her a letter, saying: “Miss Watson, your runaway nigger Jim is down here two mile below Pikesville, and Mr. Phelps has got him and he will give him up for the reward if you send. Huck Finn.”

About 50 pages later, Huck has pangs of conscience about helping Jim escape Miss Watson — “stealing a poor old woman’s nigger that hadn’t ever done me no harm” — and decides to write her a letter, saying: “Miss Watson, your runaway nigger Jim is down here two mile below Pikesville, and Mr. Phelps has got him and he will give him up for the reward if you send. Huck Finn.”

Initially, Huck feels “all washed clean for sin.” He’s done the right thing as white American society would have it. He’s upheld this white woman’s property rights.

But he sets the letter down and begins to thinking:

“And got to thinking over our trip down the river; and I see Jim before me all the time: in the day and in the night-time, sometimes moonlight, sometimes storms, and we a-floating along, talking and singing and laughing. But somehow I couldn’t seem to strike no places to harden me against him, but only the other kind. I’d see him standing my watch on top of his’n, ’stead of calling me, so I could go on sleeping; and see him how glad he was when I come back out of the fog; and when I come to him again in the swamp, up there where the feud was; and such-like times; and would always call me honey, and pet me and do everything he could think of for me, and how good he always was; and at last I struck the time I saved him by telling the men we had small-pox aboard, and he was so grateful, and said I was the best friend old Jim ever had in the world, and the only one he’s got now; and then I happened to look around and see that paper.”

He thinks and he thinks and he thinks. Finally, he says: “All right, then, I’ll go to hell.” And he tears up the letter.

Most late 19th century white Americans had little, if any, social interaction with black citizens. Yet, in Twain’s subversive, transgressive novel, the reader has come to know Huck and Jim as friends, despite Huck’s constant use of the word “nigger.”

Huck is even willing to risk Hades because of his friendship with Jim.

“Risking his freedom”

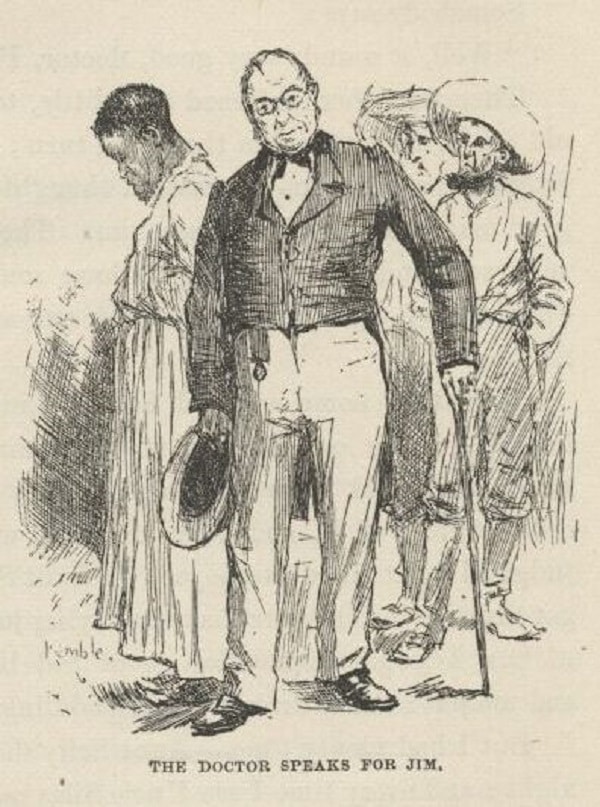

At the end of the novel, Huck and Tom help Jim escape. But Jim is soon recaptured. That happens when Huck sends an old doctor to the raft where the wounded Tom and Jim are hiding.

The men who bring Jim back to the Phelps house are giving Jim a hard time until the old doctor tells them:

The men who bring Jim back to the Phelps house are giving Jim a hard time until the old doctor tells them:

“Don’t be no rougher on him than you’re obleeged to, because he ain’t a bad nigger. When I got to where I found the boy I see I couldn’t cut the bullet out without some help, and he warn’t in no condition for me to leave to go and get help; and he got a little worse and a little worse, and after a long time he went out of his head, and wouldn’t let me come a-nigh him any more, and said if I chalked his raft he’d kill me, and no end of wild foolishness like that, and I see I couldn’t do anything at all with him; so I says, I got to have help somehow; and the minute I says it out crawls this nigger from somewheres and says he’ll help, and he done it, too, and done it very well.

“Of course I judged he must be a runaway nigger, and there I was! and there I had to stick right straight along all the rest of the day and all night…. So there I had to stick plumb until daylight this morning; and I never see a nigger that was a better nuss or faithfuller, and yet he was risking his freedom to do it, and was all tired out, too, and I see plain enough he’d been worked main hard lately. I liked the nigger for that; I tell you, gentlemen, a nigger like that is worth a thousand dollars—and kind treatment, too.”

If Charles Dickens had had a character in A Tale of Two Cities act in a similar self-sacrificial manner, the character would have been called noble.

Jim — in this scene and in this novel — is noble.

Undermine prejudices and expectations

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is a novel designed to undermine the prejudices and expectations of his time.

Even the saints among us can be silly. Even the scoundrels among us can be pitiable. Even the rich and mighty can be petty and stupid.

And even a white boy and a black man can be friends and exhibit the highest of human qualities.

No wonder this has been a powerful book for a century and a half. And part of its power has been its skillful use of a hated racial slur.

Patrick T. Reardon

2.17.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

Yep.

Amazing read. I was deeply moved as a child reading Twains works and I feel it resonates even more deeply now.

Yes. This is one of the all-time great novels. Pat

Oops- see above!

Very thoughtful and perceptive summary. I wish I’d read it as a child. Or if I had I would not have forgotten it.