The young woman and Sulien, an older man from another part of the world, are talking about birds and their movements together.

“It’s just amazing to me how they moved, almost like water. How were they able to flock together like that? Was there a leader guiding them?”

“Nope. No leader. It was all a coordinated, collective effort. Each bird followed the seven birds closest to it.”

“What do you mean?”

“Instead of focusing on the movement of the whole flock, each bird would try to make their moves sync with its seven neighbor birds. That’s why it looks like water ebbing and flowing in the sky. Because there’s a delay between each bird following its closest seven.”

The beauty and mystery of bird flight, a commonplace wonder in the lives of human beings, all the way back to when humanity began.

But notice: The young woman and Sulien are talking in the past tense.

A year or so before this conversation, the birds disappeared.

A story about another story

At our present moment in history, there seems to be a leaning among American writers toward fiction that tells a story about another story — toward stories that, in some way, are fables or fairy tales or legends or myths or parables or allegories.

Consider three recent novels. David Mamet’s Chicago (2017) is a myth that tracks its central character’s odyssey through a hyper-Chicago of the 1920s in search of truth. The Queen of Steeplechase Park by David Ciminello (2024) is a wild and wacky foul-mouthed fantasy about free-spirit Belladonna Marie Donato and her circle of boundary-breaking friends in the tight, sad world of the 1930s Depression in New Jersey and at the beach at Coney Island.

Paradise Close by Lisa Russ Spaar (2022) is a complex novel — told in three parts, spanning 1970 to 2017 — of psychic wounds suffered that continue throbbing down the years, never fully scarring over. Seemingly separate and distinct, the first two parts come together in the third in an ending that echoes the closed loop of a fairy tale — the witch pushed into her own oven, the sleeping beauty kissed, the clicking of ruby slippers at the end of The Wizard of Oz.

Mamet uses his mythic city to get behind the sparkly aspects of the life we live to what is of deep value. Ciminello plays out a what-if — what if someone could be as free and happy as Belladonna — not just in the 1930s but, even more, today. Spaar’s fairy tale-ish story suggests that, amid our modern feeling of isolation and aloneness, all human connections, when seen from the right perspective, from the right distance, are loops that close in some way.

Fable now fact

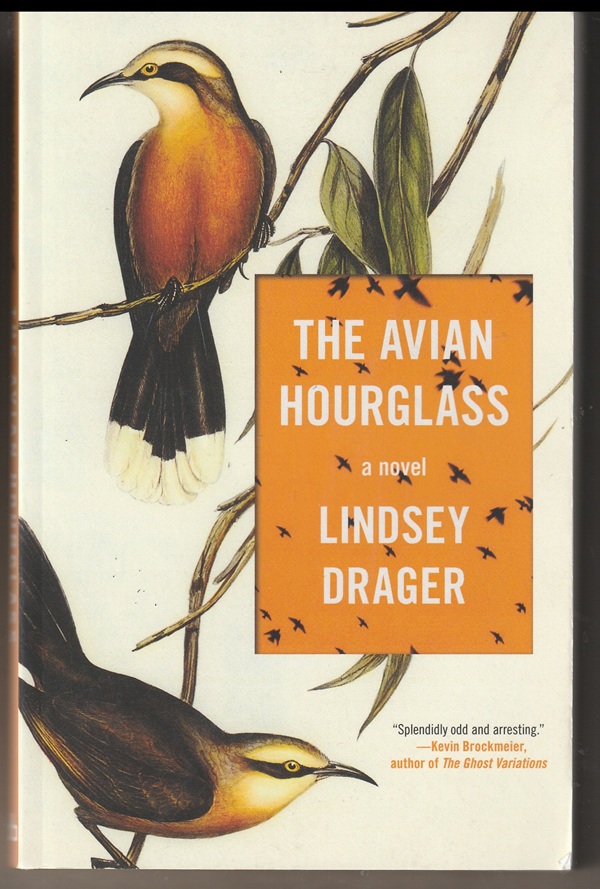

Lindsey Drager’s The Avian Hourglass (2024) is any number of stories about a story — a core story about how humans live in a world that seems beyond our control; that, in fact, may not be in our control at all; that seems to be and probably is beyond our understanding; that is, at once, mysterious and routine.

Call it, maybe, a parable of parables. Or an allegory of legends. Or a layering of yarns and epics and fables.

There is even a fable that is mentioned, described, re-told throughout the novel, Girl in Glass Vessel. It goes like this:

There’s a girl and she’s in a glass vessel. It’s tight in there. Sometimes the glass stretches and the orb gives her some room and she can walk around a bit, and sometimes the vessel gets really snug around her body, like an egg….The girl and her glass vessel exist inside a planetarium, so she can’t see the real night sky. She tells her story alone in her transparent world, thinking she is in charge of what is heard, but the whole story is curated and governed by the ghost of birds.

But, then, the planetarium splits open, and the girl sees the real night sky. But, then, it rains and dissolves the glass vessel. And, then, the rain dissolves the girl. And, over a much longer period of time, the planetarium falls apart and dissolves.

Now, at this moment, in the town and in the world where The Avian Hourglass takes place, this long-told fable has become fact.

The birds have disappeared, and the sky has so clouded over and been distorted by light effects that the night sky is never seen, not even in the rural areas away from city lights.

Her and the seven

The discussion that the young woman is having with Sulien about the movement of birds is taking place while they are putting together a makeshift planetarium to enable the young children of the town to know what the night sky used to look like.

The discussion that the young woman is having with Sulien about the movement of birds is taking place while they are putting together a makeshift planetarium to enable the young children of the town to know what the night sky used to look like.

When she hears that each bird would sync their flight with seven neighbor birds, she thinks of the seven humans with whom she syncs her life: Sulien, Uri, Luce. The triplets. The Only Person I’ve Ever Loved.

The young woman, who seems to be in her early twenties, narrates The Avian Hourglass. Her name is never mentioned. In occasional transcriptions of conversations, she is simply “Her.” That’s what I’ll call her.

The Only Person I’ve Ever Loved is a young woman, about six months older than Her, who moved away from the town in their teens. In the novel, she returns for a short time and leaves again. Her name is never mentioned.

The names of the triplets are never mentioned. In the conversation transcripts, they are One of the Triplets, Another of the Triplets and the Third of the Triplets. Her gave birth to them what seems to have been about four years ago.

Her was a gestational surrogate for their parents — “I was merely the flesh shell in which the triplets were being incubated” — but the parents were killed in a car crash five weeks before the babies were born. Her decided to keep and raise them. In this, she is helped by Uri, the brother of their dead mother, who took an early retirement and lives next door to Her and the triplets in a duplex.

Luce is the twin sister of Her’s father who died of a heart attack about ten years ago after many mental health problems. Sulien is a town resident whose partner also seems to have died after mental health problems.

Uri, Luce and Sulien are all about twice as old as Her. On the last page of the novel, Her mentions that their names all mean “light.”

Her is an only child. Her mother is never mentioned.

Perspectives

The story of Her and her seven is the shell story through which Drager raises her core questions about how humans live in a world that seems beyond our control; that, in fact, may not be in our control at all; that seems to be and probably is beyond our understanding; that is, at once, mysterious and routine.

Girl in Glass Vessel is something like a mirror in which Her and her seven look at their lives.

Drager’s novel looks at her core questions from a galaxy of angles and perspectives — and always from the individual viewpoint of Her.

YES, NO and The Crisis

The name of the town where these characters live is never mentioned. It is connected to the world through the internet, but there is no mention of anyone coming to or leaving the town with the exception of The Only Person I Ever Loved.

The town and the world are living in The Crisis. This seems to be an environmental calamity. Peninsulas have turned into islands. Islands have disappeared. Some places have become uninhabitable. The birds have disappeared, and the night stars cannot be seen.

For the past four decades, the town has had a weekly gathering, called variously The Demonstration or The Rally or The March. There are always two sides: YES and NO.

My heart lies in neither side but it is part of the local culture to participate so in the interest of fairness I demonstrate for both. When on the YES side, there is optimism and hope which the NO side says is false and misleading. When on the NO side, there is cynicism and fact-facing which the YES side says is not productive in inaugurating change.

The truth is I believe we are all really hurting because of the Crisis, especially since the last bird disappeared. I believe when we reached the end of birds — birds, whose genetic code outlived dinosaurs — people realized we were at the precipice of a whole new paradigm of being.

Sad, confused, unsettled

This novel is not the sort of a fable that lends itself to the search for a key. Her and her seven and everyone in their town spend the book hunting for answers but only reap questions.

It’s not the sort of allegory that fits snug. It’s dozens of allegories simultaneously, and they clatter and clack together in a clashing non-harmony.

Her and her seven and everyone in their town are sad in the face of the mysteries of their existence. And confused. And unsettled.

The birds are gone. The stars are hidden. What next?

Beyond that, what does it all mean? What does any of it mean?

A courageous novel and novelist

The Avian Hourglass is not an environmental novel, warning of what the human race faces in the future. Its action occurs in the context of a global disaster, yet its questions are those that every generation of humans — every human — has faced, will face. Faces today.

It is a courageous novel that wrestles with the idea of God although the word God is never mentions.

Luce is talking about quitting her work at the Factory that used to be the Farm. Her tells her to do what Luce’s fathers — Her’s grandfathers, Granddad and Papa, who loved each other deeply — did. They custom-made globes for all sorts for people.

“Make globes,” I say, just like that. “Make worlds,” I say, and my blood aches with the knowledge that everything is aligning just the way whoever is in charge — which is not me, not me by a long shot — everything’s aligning as whoever is in charge thinks it should.

The Avian Hourglass wrestles with the interrelation of Nature and humanity, of the Cosmos and the Earth, of parallels (like twins and triplets) and incongruities.

It is also courageous in its complexity. And in Drager’s willingness to raise deep, dark questions in a story that doesn’t answer them.

This is not a usual book. It is a rich work of art for those who are willing to open themselves to Her and the triplets and Luce and Uri and Sulien and The Only Person I Ever Loved — and to the aching, hurting, bruised world in which they live. (Which is ours, only under a different name — never mentioned.)

Patrick T. Reardon

4.11.25

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.