The girl walks down to the lake to the spot where she and her father fish. A goose and gander and five goslings are there, making a home for the summer for themselves.

The girl is ten. As she approaches the water, she startles the geese. The goose shepherds the goslings into the water as the large gander comes at the girl, stabbing her leg with his beak and then striking again, wounding the arm she puts before her face.

In a few days, when her arm and leg feel better, the girl goes back to the water with her bow and arrow.

The gander was no more than ten yards away. It saw the girl emerge from her cover and squawked at its mate, then raised its head and body to full height, thrust out its wings and neck, and rushed at the girl….

Then the girl released the arrow and sent it straight through the gander’s chest at near point-blank range.

She nocked another and moved toward the water, where the mother goose had opened her wings in one last effort to cover her young, … She drew the arrow and fired in one swift move, hitting the goose square in the back and pinning it to the bottom of the shallows.

Useful

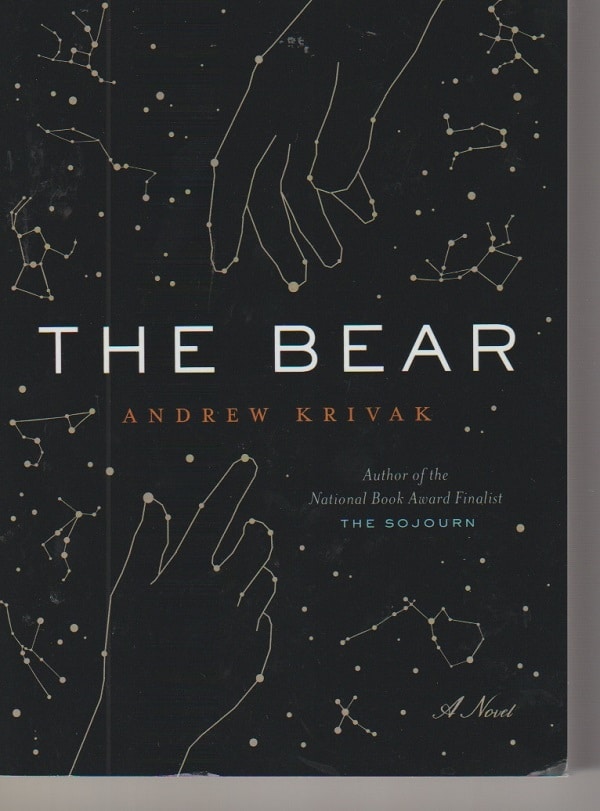

Andrew Krivak’s The Bear is a sharp-edged parable about life and death, about ends and beginnings, about journeys and sitting in place, about humanity and Nature, about what it means to be alive.

In his first sentence, Krivak tells the reader, “The last two were a girl and her father who lived along the old eastern range on the side of a mountain they called the mountain that stands alone.”

These two, the last of humanity, far beyond the need for modern civilization, exist in rhythm with the forest and the seasons, with the stone of the mountain and the wanderings of animals and the uses of berries and plants, with the stars and the mud.

These two, the last of humanity, far beyond the need for modern civilization, exist in rhythm with the forest and the seasons, with the stone of the mountain and the wanderings of animals and the uses of berries and plants, with the stars and the mud.

But, as the scene of the girl with the geese shows, theirs is no dreamy sentimental encounter with the natural world.

The geese had taken over the fishing area of the girl and her father. To leave them alone would mean finding another place to fish. Besides, the goose meat and feathers would be useful.

“As if to fly”

Krivak’s prose seems to fit with some natural rhythm, as well. It appears simple. There are few complex sentences. Yet, there is running underneath the words a poetic complexity that mirrors the subtle complexity of the interaction of the man and the girl with Nature.

Consider this scene from a long journey that the girl, now 12, must make alone, a trek that takes up fully half of The Bear. She has been walking through heavy snow from the first fall of winter and finds herself at a river that she must cross.

She brushed back the snow cover on the surface, the ice cloudy and grainy between, and lay down on her belly to spread her weight and listen…She rose on all fours and crawled out another five steps on her knees. Then she stood and walked out three more…. She knelt down to look once more at the surface, then stood….

She took four more steps toward the shore, put her arms out as if to fly, and set out across the ice, first at a trot, then running as fast as she could over the snowpack that shrouded the river.

A world they don’t rule

This is a beautiful example of Krivak’s simplicity of language. These few, short words describe the girl’s actions but also hint at other layers of meaning.

The movement of the girl to lay down on her belly on the ice says something about the visceral ways in which she and her father have woven themselves into the fabric of their landscape and environment.

Similarly, this scene suggests the humbleness that the girl and her father bring to living in their world.

Unlike moderns (and probably civilized people going back down all the centuries), these two recognize that this is a world they don’t rule. As the girl was with the geese, so is Nature with them. They are frail biological mechanisms that have only themselves to keep themselves alive. The wrong decision can result in death.

Nonetheless, she is still a girl, and elation is still a feeling that all animals, including humans, feel — especially the elation of being able to run on a flat surface after spending three days slogging through deep snow.

“Exploded”

Immediately after the description of the girl running across the ice, there is the usual space between that section and the next. And the new section begins:

There was no crack, no movement, no sound like a moan. The ice exploded and she fell through as though she were a stone, a gasp of surprise the only air she took with her as she shot down.

Again the simplicity of language, but used now not to describe the girl’s caution but her shock.

The initial sentence is flat and simple, almost dull — like the ice. Then, in one sentence, Krivak makes the reader feel the ice exploding under the feet of the girl and her falling like a stone, “shooting down.”

Will you hold me?

I am a city boy. I’m anxious any time I’m away from sidewalks and toilets and other accouterments of civilization.

Krivak’s novel describes an existence that is very foreign to me, as if it were a science-fiction novel about living on a strange new planet.

Of course, the world that the girl and her father live in is the same one where I live. I’m just far removed from the rhythms and aromas and languages of this natural landscape.

When the girl gets down to lay on the ice, she is testing its weight-bearing abilities. But she’s also asking it a question: Will you hold me?

The mystery of existence

From the little I know of people who spend a lot of time away from civilization, there is a communication like this that goes back and forth on many levels between a human being and the natural world.

Nature talks. It tells things to a human if the human is able to look and listen.

This is a very nitty-gritty language but also mystical. I have no experience in this, but I can see what people mean when they talk about communicating with nature.

So, in The Bear, when the girl has conversations with individual animals, I understand this in a way. But it is very foreign to me.

It’s also foreign to me when saints describe their ecstatic union with God. It’s foreign to me when I see an artistic creation — Picasso’s Guernica or Shakespeare’s King Lear — and know that, in some unknowable way, this object has been created through a process that involves much more than thought and reason.

Krivak’s The Bear seems so simple. Yet, it is submerged in the mystery of existence.

In this novel, the girl and her father don’t pretend they have this mystery explained. They approach it with humility and respect.

That is the moral of this parable.

Patrick T. Reardon

4.9.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.