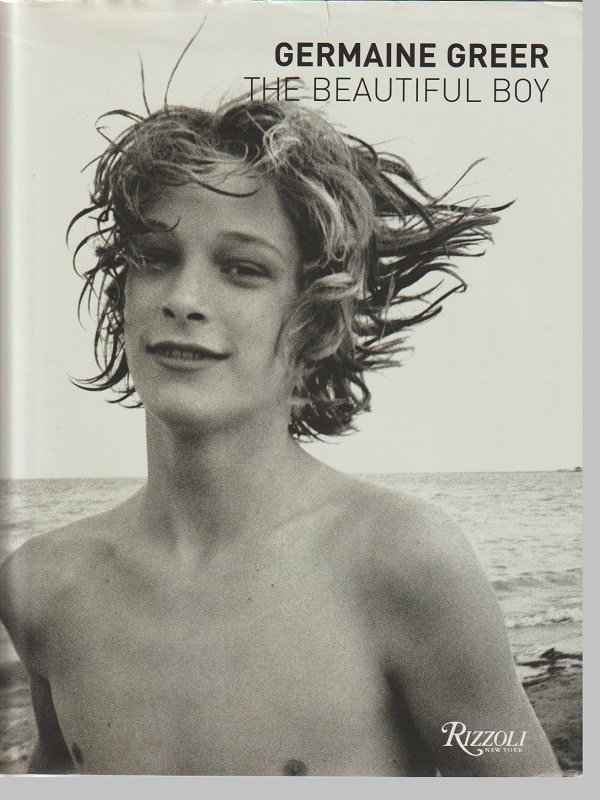

With its photo of the hair-blown actor Bjorn Andresen on the dust jacket and its striking, in-your-face, black-and-white photographs of penises at the beginning and end of the book, Germaine Greer’s The Beautiful Boy is designed to be unsettling.

At first glance, the temptation might be to dismiss the 2003 book as a soft-core volume for gay men.

Yet, Greer, provocative as usual, argues that beautiful boys are simply beautiful, and that such beauty can be admired and enjoyed esthetically by women and heterosexual men —by any human being with eyes to see.

As evidence, she trots out nearly two hundred paintings, prints, photographs and sculptures from 2,500 years of art in which nude or near-nude boys cavort, preen and exhibit a wide range of feelings — such as arrogance, distress, joy and desire — in scenes that, often, also feature fully dressed females.

Beyond that, Greer’s other goal — her primary goal — is assert the female gaze and its own sexual pleasure at beholding such beauty.

The erotic interests of girls and older women are seldom acknowledged by the mainstream culture, which allows itself to presume that the images of the most outrageous flirtatiousness will pass unnoticed….

Part of the purpose of this book is to advance women’s reclamation of their capacity for and right to visual pleasure.

Boys being beautiful boys

Starting in the 1800s, the rules of Western society shifted, for a variety of reasons, and only men were permitted to lust. Women were expected to have no interest in sex, and those who expressed such an interest were written off as depraved. With the various waves of feminism, that has changed.

By the end of the twentieth century female appetite for sexual stimulus had been recognized and platoons of male strippers mobilized to take commercial advantage of it.

Such craving, though, doesn’t have to be limited to such crass outlets, Greer asserts. It can be enriched by seeing the object of lust in the context of art, an art that, prior to the nineteenth century, was more than willing to let boys be beautiful boys.

As with girls in their teens and on the verge of becoming women, an essential element of a boy’s beauty is his youth and its fragile impermanence. As Greer writes:

Delight in the boy can only be sharpened by the pathos and irony of his condition of becomingness. What we see in life is gone before we have had time to appreciate it. It is only in art that the compellingly evanescent charm of boyhood can be preserved against the ravages of time.

Celebrated the body

In 1888, when Dorothy Tennant painted The Death of Love, she was tightly constricted by the constrictive expectations of her time. While the female figure bending over the dead Cupid is “a voluptuous arrangement of modelled curves,” the boy-god’s corpse “is flattened and all anatomical detail bleached out.”

That was how it was at the end of the 19th century when the viewer was expected to be a male who would be interested in the female body, not that of a male.

Yet, consider two examples from the history of art in the prior centuries when beautiful boys, often nude or semi-nude, were everywhere to be seen — as angels, as gods, as martyrs, as servants, even as soldiers.

These two sculptures of David, after the slaying of Goliath, one by Michelangelo (1504) and the other by Donatello (1440s), have been revered art works since their creation in the Renaissance.

And the bodies they present are anything by flattened. Indeed, far from bleaching out anatomical detail, the sculptors have celebrated the boy’s body — its muscles and sinews, smooth skin, pleasing proportions and its penis.

Didn’t shy away

Over the centuries, going back to the Greeks and Romans, artists didn’t shy away from depicting the genitals of beautiful boys. Caravaggio is an example, such as in his Love Triumphant (about 1599):

Here, Cupid, clearly male, younger than a teen, is depicted as anything but innocent, anything but flattened. (Compare this to the Tennant painting.)

While others have read the painting as a reference to homosexual pedophilia, Greer counters that the musical instruments and other props suggest, instead, a story of a man and woman who “may have been playing and singing in consort and retired to make love, hence, Cupid’s victory.” He is, after all, the god of adult intercourse.

A smirking and a sleeping god

Although known for austerity and high moral purpose, Jacques-Louis David portrayed in 1817 the smirking sunburnt boy-god, in Cupid and Psyche, as he slips out of a bed where his blazingly white, sated consort dozes.

In this image, Cupid’s penis is discreetly covered by a blanket. But it’s clear what’s just occurred.

The same is true in Venus and Mars, painted more than three centuries earlier, by Botticelli.

Mars is out cold in a post-coital sleep, and his genitals are draped by a white sheet. But his body is beautifully rendered. Across from him is the thoughtful and fully dressed Venus.

Saints and angels

The gods of Rome and Greece, however, haven’t been the only ones depicted as beautiful boys in various stages of undress. So have saints, such as in St. Sebastian by Mantegna (1458) and The Martyrdom of St. Florian by Albrecht Altdorfer (about 1515):

Even angels, for example, this all-but-naked one who is playing music in the book that St. Joseph holds while, to the right, Mary cuddles Jesus. The work is Rest on the Flight into Egypt (1597), painted by Carivaggio.

Even Jesus.

There are myriad images of Jesus as a baby and as a full-grown man, but few as a boy. One of those few is Sleeping Christ with John the Baptist by Guido Cagnacci (1640).

Cagnacci has emblematized the fragile beauty of the unconscious boy by the parallel of the bowl of roses on the table beside him….Christ’s arm is lifted above his head and his fingers are sunk in his curly hair.

Public figures

In more modern times, public figures in their teens and early 20s have been also shown as beautiful nudes.

One was a 13-year-old boy named Francois-Joseph Barra who, during the French Revolution, was killed by hoodlums in a robbery. Rewriting the facts, Robespierre transformed him into the victim of royalist troops and a hero of the Republic who died clutching the tricolor cockade close to his heart.

The boy had been fully dressed at the time of his murder, but, in The Death of Joseph Barra (1794), Jacques-Louis David portrayed him fully nude, except for the revolutionary ribbon in his hand.

Jumping ahead to our own times, young male entertainers of all sorts have parlayed their beauty into greater publicity and fame, particularly actors and popular musicians.

An early example of this is the 1972 Annie Liebowitz photo of a 21-year-old David Cassidy for Rolling Stone magazine. At the time, Cassidy was the highest paid performer in the world.

The image of the nude singer, down to his thick pubic hair (but no lower), gained great notoriety.

A pleasure

Whether the beholder is female or male, straight or gay, The Beautiful Boy is a pleasure to read and ponder.

In its way, Greer’s book is a manifesto against the 200-year tendency to want to turn boys into manly men. That has begun to change in these times, but being a football player, even if not the quarterback, still brings higher status to teen boys than dancing ballet, even if a lead.

Greer gives herself and her reader permission to see boys being beautiful boys.

Beauty is beauty.

.

Patrick T. Reardon

12.29.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.