When Jane Austen wrote The Beautifull Cassandra at the age of 12 in 1788, she added the subtitle: A Novel in Twelve Chapters.

That’s a big claim for a work that, Austen expert Claudia L. Johnson notes, contains “only 465 occasionally misspelled words.”

We tend to think of novels as somewhat heftier, but The Beautifull Cassandra was the work of a young author in training. It is among a group of her writings that Austen scholars have called “juvenilia” or “minor works” or, more recently, “Teenage Writings.” Johnson, a Princeton University English professor, writes:

Variously described — by Austen herself — as novels, tales, odes, plays, fragments, memoirs, and scraps, the juvenilia consist of twenty-seven pieces written from 1787 to 1793, when Austen was between the ages of eleven and eighteen.

To put these pieces in context, it was nearly a quarter of a century later, in 1811, when Austen, then 35, published her first actual novel Sense and Sensibility.

From one to four sentences

The twelve chapters in Austen’s “novel,” which range from one to four sentences each, average about 35 to 40 words. Here, for instance, is Chapter The Eighth:

Thro’ many a Street she then proceeded & met in none the least Adventure till on turning a Corner of Bloomsbury Square, she met Maria.

Although, in this, Austen seems to promise an Adventure, such hopes of the reader are dashed in Chapter The Ninth:

Cassandra started & Maria seemed surprised; they trembled, blushed, turned pale & passed each other in a mutual silence.

A charming book

Published in 2018 by Princeton University Press, The Beautifull Cassandra is a charming book. It tells of a walk that the sixteen-year-old Cassandra takes one day in London, wearing “an elegant Bonnet” that, on a whim, she appropriated without asking from her mother’s shop.

In one chapter, she takes a coach to Hampstead and back, and, when the coachman demands payment, “She placed her bonnet on his head & ran away.”

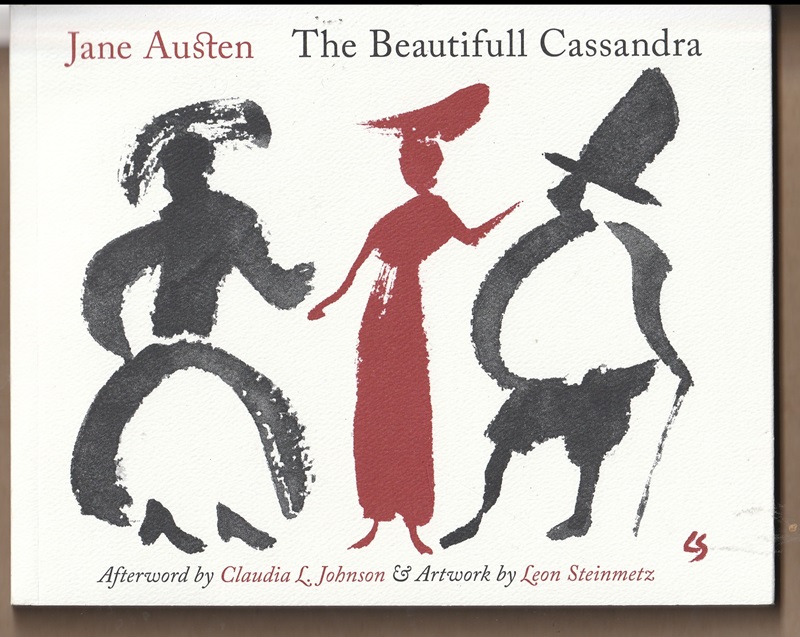

Adding to the appeal of the small, attractively designed book are Leon Steinmetz’s engaging drawings, executed with a large Chinese calligraphy brush.

Johnson writes that Steinmetz doesn’t try to represent Regency period fashion:

Maintaining their own contemporary character, [Steinmetz’s drawings] are instead a series of conversations with the text. As conversationalists, Steinmetz’s drawings and Austen’s novel are splendidly well-suited to each other.

They are each masterpieces of economy, with only a few sentences on one side, and a few brushstrokes on the other.

Fulsome praise at its most fulsome

Johnson has devoted much of her long scholarly career to Austen and her work, publishing Jane Austen: Women, Politics, and the Novel in 1988 and Jane Austen’s Cults and Cultures in 2012 as well as 30 Great Myths about Jane Austen in 2020 and The Blackwell Companion to Jane Austen in 2005 (both with Clara Tuite).

In addition, she has prepared editions of Austen’s Mansfield Park, Sense and Sensibility, Northanger Abbey and (with Susan Wolfson) Pride and Prejudice.

No wonder Johnson is much taken with this pre-teen’s “novel.”

I agree with her that Austen’s whimsical words and Steinmetz’s playful drawings go together well. Those drawings are done with subtle art and yet also suggest the sketchy, simplistic work of a child.

Are they, as Johnson writes, “masterpieces of economy”? That seems a bit of an overstatement to me.

I have even more trouble with her assertion that The Beautifull Cassandra is a “masterpiece of novelistic minimalism” that “deserves to be read by everyone who loves Jane Austen, by everyone who loves novels, by everyone who possesses a keen sense of the absurd, by every parent to every child in the interests of cultivating an ear for the cadences of English prose, by everyone who loves a laugh.”

This is fulsome praise at its most fulsome.

Overselling?

Johnson is the expert, and she’s reading The Beautifull Cassandra in the light of the true masterpieces that came later, such as Pride and Prejudice and Emma.

She sees a book that parodies the literary conventions of the day. And one that “shows us how exquisitely tuned Jane Austen’s ear was” to the rhythms and sentences of English prose.

I see a book written by a talented 12-year-old who is having a high time stringing together a series of fairly unconnected non-events.

Indeed, this doesn’t so much remind me of Austen’s Emma as it does the sort of run-on story that children from the age of three to, well, 12 are wont to tell: “….and then this happened….and then this happened….and then this happened.”

To my mind, Johnson oversells the significance of The Beautifull Cassandra.

The mind, heart and talent

Which isn’t to say the “novel” is insignificant.

It provides a window into the mind, heart and talent of a girl who would become one of the great English novelists.

Even more, it’s a lot of fun. In her “novel,” Austen tells a silly story. It is in the form of something literary, but, at its heart, it is play.

And play, for all the happiness it can provoke, is serious work. Austen set out to tell a story that, by its mix of the mundane and the absurd, would spark smiles and laughter.

She succeeded back in 1788 in her family circle, I’m sure. And, in this edition from Princeton University Press, she succeeds anew more than two centuries later.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.10.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.