Chester Himes published his hardboiled crime novel The Big Gold Dream more than sixty years ago, and, for a present-day reader, it is something of a time capsule.

It depicts New York City’s Harlem at a time when it was seen by mainstream society as an African American slum, far from the gentrifying neighborhood of the twenty-first century. And it focuses on the petty criminals, working hard to keep their heads above water through the numbers racket, drug sales, prostitution and assorted other schemes and dodges.

In the opening scene, Alberta Wright is among six hundred white-clothed converts filling 117th Street as they await baptism from Sweet Prophet Brown:

Her big brown cowlike eyes cast a look of adoration across the gleaming white sea of kneeling worshippers upon Sweet Prophet’s exalted black face.

Sweet Prophet tells the crowd, “Faith is so powerful it will turn this dirty black pavement into gleaming gold….Put your trust in the Lord!” At which, Alberta jumps up to announce that she did trust the Lord and He sent her a dream.

“I dreamed I was baking three apple pies. And when I took them out of the oven and set them on the table to cool the crusts busted open like three explosions and the whole kitchen was filled with hundred-dollar bills.”

And then two things happen:

Alberta dies, except she doesn’t. She’s just unconscious, but enough out of it that she’s sent to the morgue.

And a mad dash — several mad dashes — begin to take place all across Harlem to find the money that many lowlife criminals, including her husband Rufus Wright and her boyfriend Sugar Stonewall, think she has hidden somewhere.

Quirky oddities

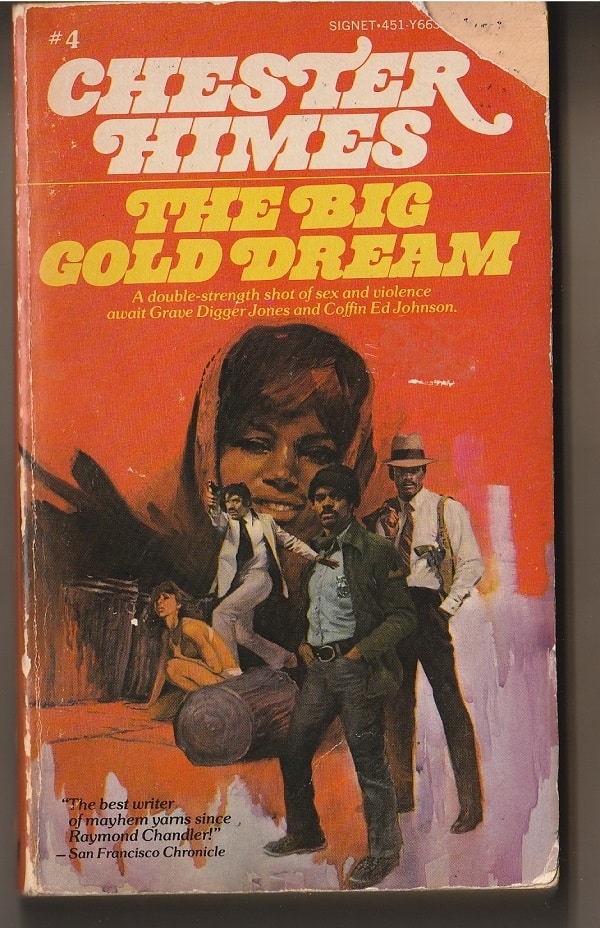

The Big Gold Dream was the fourth of nine novels that Himes wrote in his Harlem Detective series (1954-1983), featuring two tough Black NYPD detectives Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson.

In this book, however, Grave Digger and Coffin Ed make an appearance early and then don’t show up again until the last twenty pages or so. That’s when they are trying to save Alberta from really dying because of the violent types who want whatever it is she’s got — if she has anything.

Until then, Himes tells of the half-baked hustles of a small mob of lowlife criminals, some of whom die in their efforts to get what they believe Alberta has hidden. They think it’s some sort of money, and their belief in that is reinforced by the growing number of people looking for it.

These would-be thieves are interesting in their quirky oddities. For instance, Dummy is a former welterweight boxer who lost his hearing from getting punched too much and lost his tongue when his criminal backers wanted to make sure he wouldn’t testify against them to investigators. He communicates with other characters by scribbling notes on a pad of paper.

Another is a dude called Susie who smokes a lot of pot and wears cowboy boots. A third is Abraham Finkelstein, a devious white businessman who specializes in hiring guys to break into the apartments of people who are out of town and then “sell” him the furnishings.

From the beginning of the story, Finkelstein is known most of the time as simply The Jew.

Politically incorrect

That is one of the many ways that The Big Gold Dream is a throwback. It would be the height of political incorrectness today to call a character The Jew, but, in 1960, the term was, to some extent, socially acceptable in terms of how the characters in Harlem would speak.

Besides, it was being used by Himes as a descriptor rather than a slur. Indeed, Himes, I suspect, would argue that it wasn’t antisemitic to employ the term since Finklestein was just one of many people in the story who were willing to use illegal means to get money that didn’t belong to them. He was more skillful than some, and less skillful than others.

Of course, in today’s era of Black Lives Matter, the idea of centering a story on a bunch of Black criminals probably wouldn’t fly. It would seem to be giving some sort of endorsement to them and their illegal activities, and they would be seen as well as poor representatives of African American life.

Yet, Himes doesn’t portray these guys as heroes but as bumbling, if violent, schemers. What’s striking is that, even though the reader doesn’t know all of the mystery, the reader usually knows more than the schemers and can see how misguided and dense they often are.

Not only that, but a number of the schemers get killed because of their scheming. In fact, two die for money that isn’t money. (I could explain that, but it would spoil the plot twist.)

A lot of thievery and violence

It can seem, for a present-day reader, that there is a lot of thievery and violence going on for small amounts of money. For example, after Alberta’s “death,” Finkelstein buys the furnishings of her apartment from Rufus for $117.

However, those were 1960 dollars. After six decades of inflation, the equivalent of that money today is about $1,200. Similarly, one chunk of change that a character gets ahold of sounds like a lot, $36,000.

But, in today’s dollars, it’s much more — ten times more.

“The man”

The portrayal of the police by Himes carries none of the deep antipathy that many Blacks express today toward law enforcement officers, regardless of race. The white cops are presented as fairly neutral outsiders who are pretty mystified by the Black culture of Harlem but still try to do their jobs.

The best way they’ve found, as Himes presents it, is to let Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson, their Black colleagues, do the heavy lifting.

Grave Digger and Coffin Ed are clearly the heroes of this book in terms of Black men who are attempting to impose order on a chaotic Harlem and keep the Black criminals from ruining the lives of the other African American residents.

Twenty minutes later they saw Sugar Stonewall alight from a Fifth Avenue bus and cross the street. Coffin Ed intercepted him and took him by the arm.

“I’m the man,” he said.

“First time I was every glad to see the man,” Sugar confessed.

“Like warriors of old”

A few pages later, the two detectives are heading to the apartment where they think Alberta Wright is being held — and tortured.

With drawn pistols they started up the stairs, taking them three at a time, Grave Digger leading and Coffin Ed at his heels. Their pistols swung in gleaming arcs like the swords of warriors of old.

The Harlem and the United States of The Big Gold Dream, as Himes describes them, were much different places than what we know today. And the same is true of American Blacks of then and now.

Patrick T. Reardon

12.7.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.