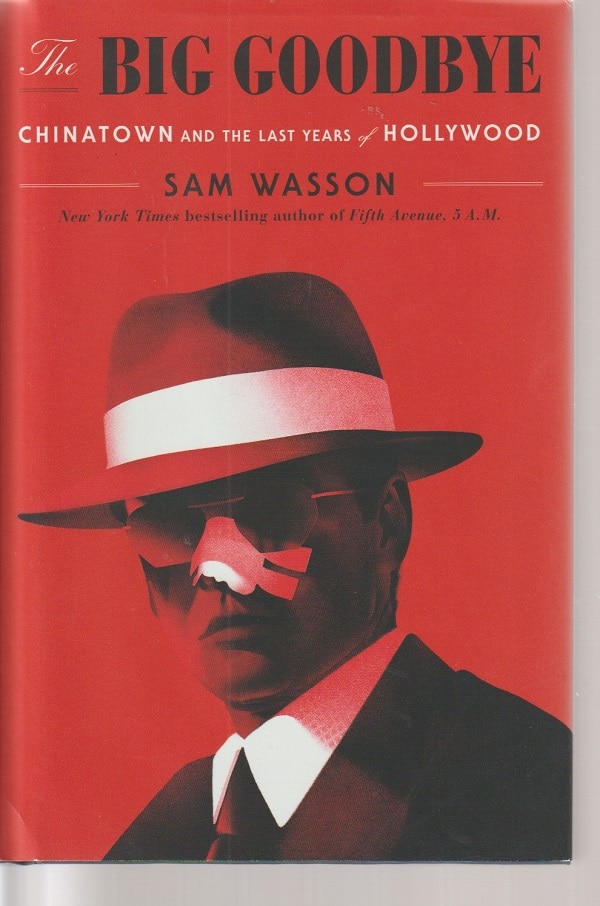

For a week or so after I finished reading The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood by Sam Wasson, the name of Roman Pulanski kept popping into my head at odd moments.

I hated that.

I hated Wasson’s book for drumming that name into my head for 331 pages.

I hated what the book showed me about Polanski — a child rapist who didn’t see what the problem was.

And I hated Wasson for spending nearly 300 of his pages promoting Polanski, the director of the 1974 film Chinatown, as a cinematic genius — and, then, only then, blithely tell the story of the child rape that led Polanski to flee the U.S., never to return.

But Polanski isn’t the only warped character at the center of Wasson’s book.

The greatest screenplay ever

Another is Robert Towne who won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay for Chinatown, considered by many the greatest ever written — even though, as Wasson shows, it wasn’t really Towne’s or, at least, not all his.

According to The Big Goodbye, Towne wrote his screenplay, as he did most of his screenplays, with the strong assistance of Edward Taylor who, Wasson suggests, should have been listed as co-writer.

But, then, when the script got to Polanski, he did a complete write-through, slicing and dicing the work of Towne and Taylor to shape it into the story that he wanted to tell.

Wasson makes a big deal throughout his book about the debt that Towne owed to Taylor in the course of his entire career. This, plus the author’s descriptions of Towne’s actions due to an alleged cocaine habit, paint a portrait of Towne as a thin-skinned, egotistical bully.

Nicholson and Evans

Polanski and Towne are two of the four central characters in The Big Goodbye. The third is Jack Nicholson, who might just as well be called Saint Jack throughout the text. In contrast to everyone else, he is constant, loyal, friendly, collaborative and a great actor.

The fourth is the producer, Robert Evans, the only one of the four to talk with Wasson and a self-promoter from the word “go.” He doesn’t come across as darkly warped as Polanski and Towne, nor as angelic as Nicholson. Perhaps that’s because Wasson actually talked with him, or maybe because he was the main source of Wasson’s story.

The Big Goodbye is what we used to call in my newspaper days a clip job. You take a heap of stories that have been written about a subject, and you stitch them together into a new story.

The Big Goodbye is what we used to call in my newspaper days a clip job. You take a heap of stories that have been written about a subject, and you stitch them together into a new story.

There are a lot of quotes in this book from Polanski, Towne and Nicholson, which is to say, quotes taken from conversations with other interviewers. And there are a lot of quotes from ancillary people about the four principals and about the creation of Chinatown, some of whom talked with Wasson and others whose words come from other sources.

Ultimately, The Big Goodbye feels like a story told at a distance, and a hazy distance at that.

A tendency to overwrite

Adding to this murkiness is the tendency of Wasson to overwrite.

Consider the subtitle about “The Last Years of Hollywood.” How many news and feature stories have had that that phrase in a headline? How many books have worked that idea into a title or subtitle? I don’t know what specifically Wasson means with those words, and he doesn’t really explain.

And then there’s his purple writing. For instance, Wasson writes that 1974, the year Chinatown premiered,

“represents the final flowering of a film garden passionately tended by liberated studio executives and an unspoken agreement between audiences and filmmakers.”

What?

At another, he writes about the shooting of a scene in an orange grove:

“A hot breeze, the sound of secrets whispering the oranges.”

At another, Nicholson opens the door to a visitor,

“the evening sun singing in around him.”

“An American metaphor”

Finally, there is this assertion from Wasson:

“What makes Chinatown so uniquely disturbing as an American metaphor is that it is so unlike the whiteness of Ahab’s whale or the greenness of Gatsby’s light.”

I get it, Chinatown is a great film. But to compare it to Moby Dick and The Great Gatsby?

I’m no film scholar, and I’m open to the idea that a case can be made that this film is an equal to those monumental works of American literature. But Wasson doesn’t make a case for that in his book. He just makes bold, blanket statements, as if it’s all well understood.

Instead, his book, with its warped, self-promoting or angelic characters, is an extremely detailed recounting of every twist and turn in the creation of this movie.

Target audience?

Leaving aside the question of how accurate this recounting is, given that three of his central characters didn’t talk with Wasson, the question I had reading The Big Goodbye had to do with the target audience.

Certainly, the book is aimed at anyone who makes movies or used to or wants to, and anyone who is a huge fan of Chinatown. For a film student, this book might be a lesson in what not to do — or maybe that even the craziest group of people can somehow create something very good.

But the general public? Does Joe Average-Reader want to slog through esoteric — although, at times, titillating — details of the movie’s creation? I don’t think so.

For me, I wasn’t all that interested in Chinatown when I started this book, and, now that I’ve finished, I’ll watch it again and maybe have new insights into it.

A great work of art

Maybe, if someone offered me a book about all the intrigue and rewrites and backstage fights that led up to the first performance of King Lear, I might read it. But maybe I wouldn’t.

As someone who has created thousands of newspaper and magazine stories as well as a handful of books, I’m more interested in a reader encountering my finished product than watching me go through my process of getting it written.

A great work of art, such as King Lear or Moby Dick or The Great Gatsby, is a great work of art.

The backstory, really, isn’t important at all.

Patrick T. Reardon

3.22.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.