As P.D. James’s 1975 mystery The Black Tower opens, Police Commander Adam Dalgliesh has just learned that the doctors made a mistake. He’s not going to die of acute leukemia. He just had a case of what they’ve decided was atypical mononucleosis.

“I congratulate you, Commander. You had us worried.”

“I had you interested; you had me worried.”

Having reconciled himself to a rapidly approaching death, Dalgliesh is somewhat flummoxed by this “sentence of life.” He’d gone through the mental and emotional steps of letting go of so much of his former life that, with this unexpected reprieve, he’s at loose ends.

For one thing, he’s sure he won’t go back to policing.

“Your professional advice”

But, before he can decide what he will do with the rest of his life — thinking in terms of years, not days — Dalgliesh receives a letter from Father Michael Baddeley, a mentor from his childhood. The aged Anglican priest has asked the detective to visit him at Toynton Grange, a private home for disabled people in the far southern county of Dorset, so he can solicit “your professional advice.”

Two weeks later, “still weak with his hospital pallor but euphoric with the deceptive well-being of convalescence,” Dalgliesh hits the road, arriving at Toynton Grange to learn that his friend has died and is already buried. He’s also told that Father Baddeley left his small library to him so Dalgliesh is invited by Wilfred Anstey to stay in the priest’s cottage while sorting the books and getting them ready for shipment.

Anstey is the owner of Toynton Grange. Eight years earlier, while diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, Anstey travelled to the Catholic shrine of Lourdes although not a Catholic himself. He went there in a wheelchair and came back with the full use of his limbs.

This prompted him to turn the family mansion into a place where disabled people could live and be taken care of. And, to do that care-taking, he assembled a small quasi-religious community of low-paid workers under his supervision. In line with this, he and some of the others routinely wear monk’s gowns.

“A sin against Wilfred”

Ursula Hollis, a young woman newly afflicted and one of two Catholics among the Toynton Grange company, has come to recognize that she’s been dumped at the home by her husband Steve to free him to live the rest of his life without worrying about her. This realization has left her depressed and isolated.

She tried to conceal it since unhappiness at Toynton Grange was a sin against the Holy Ghost, a sin against Wilfred.

Although Anstey promotes a mood of one-big-happy-family, essentially everyone at the home is bitter, angry, frustrated, unsettled, deceitful, ashamed, miserable and/or distrustful.

And people at the home have started dying. Not just Father Baddeley, but also Victor Holroyd who, from all the police can determine, apparently rolled his wheelchair off a cliff or maybe the brake malfunctioned.

And, then, while Dalgliesh is there, come some more deaths.

The puzzles of human nature

Given the setting, it’s not surprising that many of the characters ruminate on sin and morality and the darkness under the surface of daily life.

That fits the story, but also fits the storytelling that James has been honing through four earlier Adam Dalgliesh mysteries. By this fifth novel in the series, it’s clear that her interests are less with the puzzles of plot than with the puzzles of human nature.

Many of the pages of The Black Tower are taken up with the back stories and inner dialogues of the patients and their caregivers.

James is most interested in fleshing out these people as people. Yes, they play their roles in her plot, but she enjoys creating them with all their human wrinkles and sharing them with her readers.

“A squat intimidating folly”

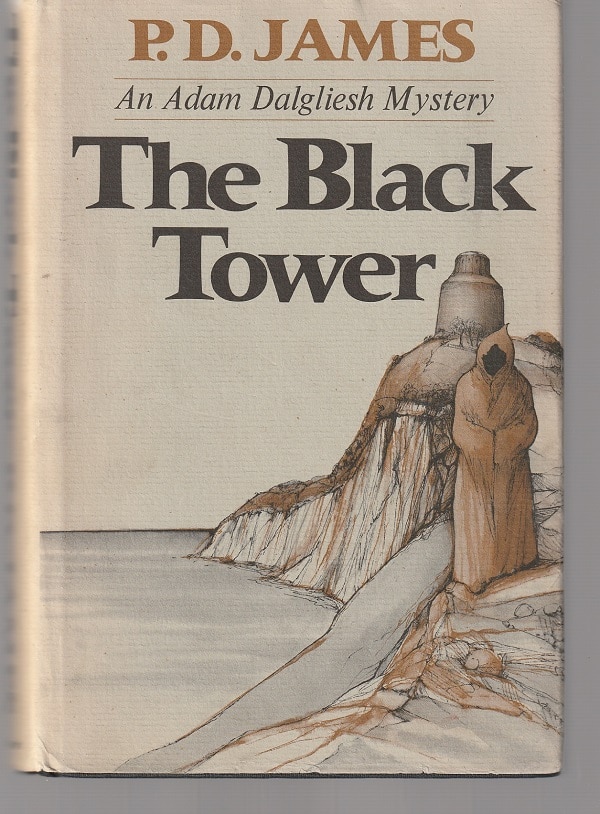

The black tower of the title is a structure that Anstey’s ancestor Wilfred Mancroft Anstey built of limestone blocks faced with shale. Dalgliesh is on a walk when he comes upon it:

It was a squat intimidating folly, circular for about two-thirds of its height but topped with an octagonal cupola like a pepperpot pierced with eight glazed slit windows, compass points of reflected light which gave it something of the look of a lighthouse…

In places the shale had flaked away giving the tower a mottled appearance; black nacreous scales littered the base of the walls and gleamed amid the grasses.

On a wall of the tower, Dalgliesh finds a plaque indicating that Wilfred Mancroft Anstey died in the tower in 1887. Not exactly by accident, as one of the Toynton Grange residents explains:

“He was one of those unamiable and obstinate eccentrics which the Victorian age seemed to breed. He invented his own religion, based I understand on the book of Revelation. In the early autumn of 1887 he walled himself up inside the tower and starved himself to death. According to the somewhat confused testament he left, he was waiting for the second coming. I hope it arrived for him.”

Moments to live

Such a tower and such a story, in the hands of another writer, could easily turn this book into a gothic novel.

However, despite some creepy parts, Dalgliesh is just too down to earth to participate in a heavy breathing horror. And, too, James’s interest in the often mundane concerns of the patients and staff of Toynton Grange counteract any tilt toward the eerie.

Some readers may judge The Black Tower to be plodding. There’s certainly no pulse-quickening action for much of the novel. James wants to focus on the characters, and her slow-unfolding story lets her do this.

In fact, in contrast to most other mysteries, no partial solutions are revealed until the very end. By page 240 of the 271-page novel, Dalgliesh is still in the dark about what has gone on and is going on.

And, then, Dalgliesh — suddenly back in full detective mode — figures it out.

And the remaining pages are filled with high tension as the man who, at the novel’s beginning, was ambivalent about his “sentence of life” now finds he may only have a few more moments to live.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.4.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.