In U.S. history, the Mormons — more formally known as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints — stand alone as the most successful, American-grown religion.

Not only did Joseph Smith, the founder of the faith, create a radically new version of Christianity. But his followers also have had an important impact on American history through their exodus to the Salt Lake area and their creation of a religious enclave centered in what is now the state of Utah. No other religious group has held sway for so long over such a large part of the continent.

The sacred scripture of the church is the Book of Mormon which, Smith testified, was transmitted to him by an angel. It is a book that the Latter-day Saints view as equal to the Jewish Bible and the Christian New Testament in terms of scriptural authority.

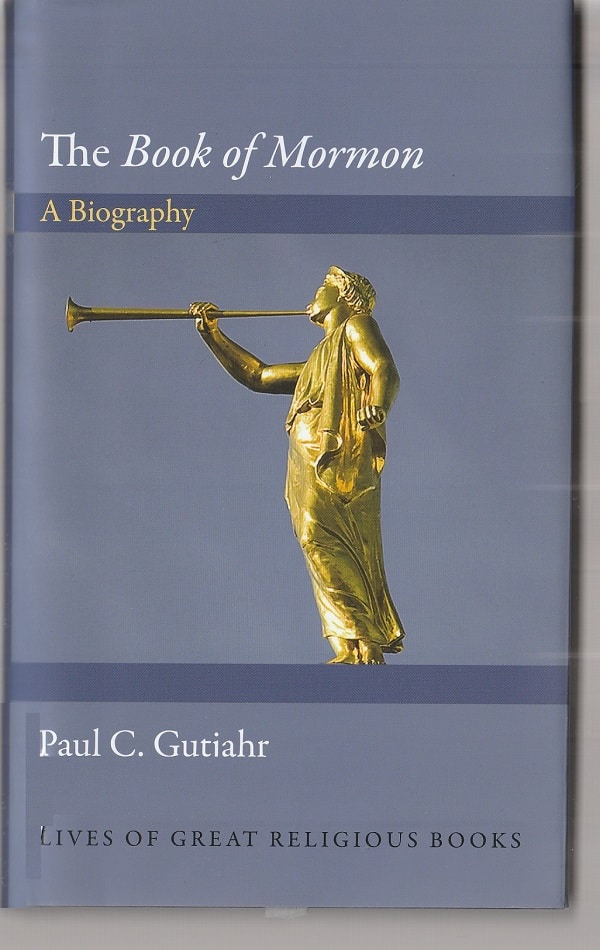

In 2012, Paul C. Gutjahr published The Book of Mormon: A Biography, as one of the first books in the estimable Lives of Great Religious Books series from Princeton University Press.

This work, like others in the series, looks at how the Book of Mormon came to be, what it says, how it’s perceived and what its impact has been not only on the Mormon faith but also on the rest of the world. Indeed, Gutjahr argues, that, for believers and non-believers, the Book of Mormon can’t be ignored:

No matter whether one considers the Book of Mormon to be divinely inspired holy writ or the work of one man’s impressive imagination, it is increasingly hard to argue against the growing scholarship consensus that “the Book of Mormon should rank among the great achievements of American literature.”

Cultural and religious

Consider that statement.

If truly the word of God, the Book of Mormon is an astonishing divine communication, on a par with the Book of Genesis or the Gospel of Matthew.

If, however, it was simply written by a man with, as Gutjah writes, an “impressive imagination,” it is an astonishing literary creation, unprecedented.

Moby Dick by Herman Melville is one of the great works of American literature, as are the poems of Emily Dickinson and Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. But none of those nor any other work of American imagination has been the foundation stone of a religious faith that now numbers more than 16 million adherents worldwide.

While the book stands as an important artifact in the study of the American history and culture, it is no less important as a contemporary religious text with global influence.

“The most important religious text”

Gutjahr points out that 90 percent of the people on Earth are able to read the Book of Mormon in their native languages. By 2011, the Latter-day Saints had distributed 150 million copies of the work worldwide.

The extensive distribution of this text is viewed by some scholars as an engine to boost the number of Mormons to such an extent that, by 2050, the Latter-day Saints could become one of the dominant world faiths, along with Islam, Buddhism, Christianity and Hinduism.

Whether or not [that] projection proves correct, it is obvious that the book that gave the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints its popular name might be considered the most important religious text ever to emerge from the United States.

Sticks to the facts

Paul C. Gutjahr, an English professor at Indiana University, is an expert in the history of books in America, having published An American Bible: A History of the Good Book in the United States, 1777-1880 (1999) and Bestsellers in Nineteenth-Century America (2016).

A non-Mormon, he approaches the Book of Mormon with the respect of a scholar. He treats the document and the religious beliefs around it with the same consideration, thoughtfulness and objectivity that secular experts bring to discussions of Islamic, Jewish and Christian scriptures.

This is in sharp contrast to the frequent tendency of non-church members, for more than a century and a half, to heap scorn on the Mormon church and ridicule its scripture.

Gutjahr doesn’t avoid looking at hard questions. What he does avoid is making broad judgements regarding matters of faith. He sticks to the facts and evenhandedly discusses how those facts can be viewed from the perspective of belief and also of skepticism.

“Sister-texts”

For instance, Gutjahr spends his book’s first chapter “Joseph’s Golden Bible” clearly delineating the Mormon beliefs and factual record of how the Book of Mormon came to be a physical book. Smith reported that, in 1823 when he was eighteen, he was given golden plates containing the new scripture from the angel Moroni. This was followed by a complex process in which Joseph orally translated the plates while a scribe wrote down his words, and thus was born the Book of Mormon.

This, Mormons believe, was a direct communication from God — one that details an appearance by Jesus in the Western Hemisphere shortly after his resurrection and tells the story of three family groups who emigrated from the Middle East to the Americas.

Not only that, but Smith preached that the Book of Mormon was one many divine communications, a radical notion in mid-19th America when the Bible was considered the sole word of God by Christians. Gutjahr writes:

Thus the Book of Mormon taught that people over vast expanses of time and space received their own revelations from God. Judea no longer possessed a monopoly on divinely inspired biblical content; throughout the ages, all the world had been filled with sacred revelation.

The Book of Mormon is just one such divine record, and the Bible simply stood as one of its sister-texts…..The implication of so many divine records not only pushed the Bible aside as the world’s single most important text, but it made the Bible a companion piece to countless other Bible-like records that, while now lost, extended God’s message to people in any place and age who might be spiritually attuned to his words.

“Either true or false”

In his second chapter — provocatively titled “Holy Writ or Humbug?” — Gutjahr recounts an interview that John Gilbert, the typesetter of the first edition of the Book of Mormon, had with the New York Times more than six decades later.

Gilbert told of meeting the son of Brigham Young, Smith’s successor as the Mormon leader, and of being asked if he thought the Book of Mormon was humbug. “A very big humbug” was his answer.

To which the Mormon leader responded: “If it is humbug it is the most successful humbug ever known.”

Another elder, Orson Pratt, made a similar assertion, a comment that Gutjahr employs at the epigraph of his book:

This book must be either true or false. If true, it is one of the most important messages ever sent from God to man. If false, it is one of the most cunning, wicked, bold, deep-laid impositions ever palmed upon the world, calculated to deceive and ruin millions who will receive it as the word of God.

Certainly, throughout the past nearly two centuries, there has been no shortage of non-Mormons who believe it is the latter.

Smith stole it?

One key argument of non-Mormons against the validity of the Book of Mormon was that it had been plagiarized from the works of an earlier writer.

The theory allowed non-Mormons to make sense of a basic tension-fraught question: How could a twenty-four-year-old, semiliterate migrant farmer [Smith] have composed such a long, complicated historical narrative? Scholars agree that Joseph had little formal education, although his father was a schoolteacher for a time and certainly helped teach Joseph what little he knew about reading and writing.

Pointing to sources other than Joseph’s imagination or a set of golden plates allowed non-Mormons to pose solutions as to how such a poor, ignorant man could have created something as complex as the Book of Mormon.

Smith made it up?

Another hypothesis was that the unlettered Joseph Smith was able to write the book because of his skill at telling tales:

Riley’s theory, and others similar to it, held that while Joseph may not have been highly literate, he had an astounding imagination and was a gifted oral storyteller. He may not have been able to write a book, but he was certainly able to dictate one.

Smith’s mother recounted that, even before he reported being given the gold plates with the Book of Mormon in 1823, Joseph had been known within the family for his spellbinding tales of

the ancient inhabitants of this continent, their dress, their manner of traveling, the animals which they rode, the cities that they built, and the structure of their buildings with every particular, their mode of warfare, and their religious worship as specifically as though he had spent his life with them.

The Book of Mormon and Genesis

The bottom line, as I read Gutjahr’s book, is that the Book of Mormon is an astonishing American creation.

Either it is a communication from God — in which case, well, there is much that Christianity, at least, has to do to incorporate the book and its message into the canon of the faith.

Or it is an amazing work of imagination that has had sweeping impact on the lives of millions of people over the past 190 years.

However, it seems to me that Orson Pratt is wrong when he asserts that, if not given to Joseph Smith by the hand of God or God’s angel, the Book of Mormon is “one of the most cunning, wicked, bold, deep-laid impositions ever palmed upon the world.”

Can a work of human imagination feed spiritual faith? Can an encyclical by the Catholic Pope do that? One of Martin Luther’s many books? The poetry of Thomas Merton or Dan Berrigan? The preaching of Billy Graham?

Consider the book of Genesis. Bible scholars can show how many of the stories in that work have their roots in earlier legends. At some point, maybe several points, a writer-editor took those stories and wove them together.

The result was a document that had not been divinely handed down but was created by a human being in such a way that it has inspired religious belief ever since. So, this work of imagination — the weaving together of these stories that, themselves, were the product of imagination (even if based to some extent on fact) — became a sacred text because of its spiritual impact on readers.

A third way?

Could that be true of the Book of Mormon, too? Could it be that the work doesn’t have to be from God or the creation of a swindler?

Could it be the work of a Joseph Smith who was filled with a faith that his Book of Mormon communicates — and a work that has inspired generations of Mormons ever since to do God’s work as they see it?

It seems a legitimate question to ask.

Patrick T. Reardon

12.6.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.